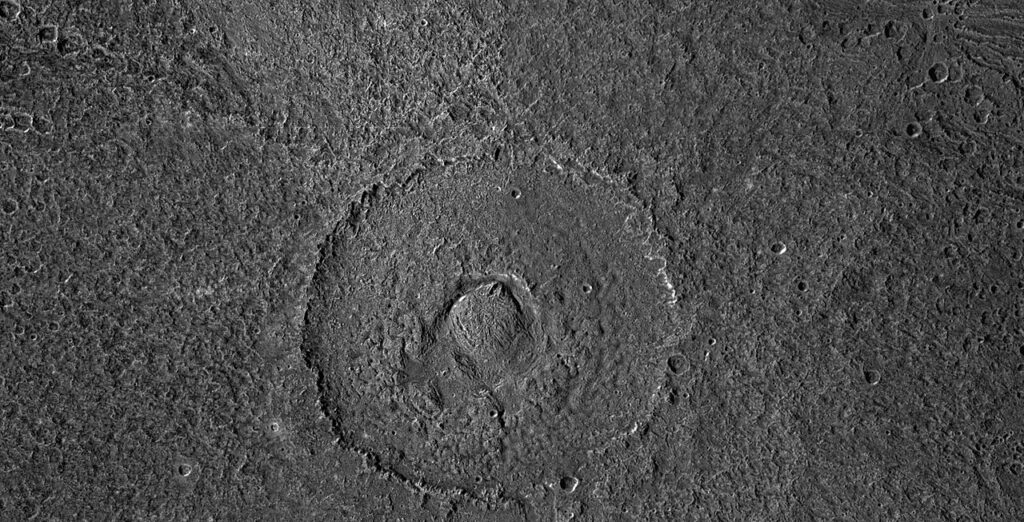

Impact basin on Ganymede

Melkart is an impact basin on Ganymede, the largest moon of Jupiter. 103 kilometres (64 mi) in size, its center hosts a distinct dome, surrounded by an irregularly-shaped depression and a rugged crater floor.

The crater is named after Melqart, the tutelary god of the Phoenician city-state of Tyre, and the “Ba’al” (or Chief lord) of the city.[3]

Its name was officially adopted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in 1979[4], in line with the convention of naming all craters on Ganymede after deities, heroes, and places from Ancient Middle Eastern mythology. The city of Tyre and its associated deities belong to Phoenician mythology, one of the many mythological traditions of the Ancient Middle East.[5]

Melkart is located on the western border of Marius Regio, a large region of dark terrain. It partially overlies a small northwest–southeast oriented sulcus that branches off from Tiamat Sulcus and connects to Sippar Sulcus.[6]: 5

To Melkart’s southwest is another dome crater called Eshmun, while to the east is a bright, grooved terrain known as Erech Sulcus.

Melkart is situated in the southern portion of the Uruk Sulcus quadrangle (designated Jg8) of Ganymede.[7]

Geography and geology

[edit]

Melkart is about 103 kilometres (64 mi) in diameter and it is surrounded by a vast bright ejecta ray system.[2]: 15

Its interior is dominated by a central dome 20–25 kilometres (12–16 mi) wide with a base–height elevation of 1.36 kilometres (0.85 mi), which is thought to have formed when warm icy material upwelled from the subsurface.[8]: 10 [6]: 2 The dome is slightly off-center to the northeast and is cut by several fractures and lineaments;[6]: 4, 6 its offset implies that the formative impactor struck the surface in a south-southwest to north-northeast direction.[2]: 15 An irregular smooth-floored depression surrounds the dome, and the crater floor has both knobbed and smooth terrain.[6]: 2 Its floor is divided into a darker and lighter section, which may correlate to the darker and lighter terrains of Marius Regio and the unnamed sulcus, respectively. A northwest-trending tectonic fault that cuts across the eastern portion of the crater delineates this divide. The fault is a right-lateral strike-slip fault, though it has a limited offset of less than 5 km (3.1 mi) at Melkart’s crater rims. The fault has two main stepover zones at the central dome’s borders, allowing for local contraction or extension.[6]: 4

Observations of Melkart’s surface spectrum from Galileo‘s NIMS instrument indicate that its surface is composed of a mixture of water ice and hydrated minerals. The abundance of crystalline water ice varies between 50 and 75%; darker regions are associated with a lower abundance in water ice and higher abundance in relatively dark hydrated minerals.[9][6]: 12–13 The lighter and darker portions of its floor, though roughly coinciding with the border of Marius Regio, does not strictly correspond to any geological units within the crater itself. This may suggest that the border of Marius Regio was gradual at Melkart’s site or that the darker material is only a shallow surface layer.[9][6]: 13

Voyager 2 became the first probe to observe and image Melkart during its flyby of Ganymede and the Jovian system in July 1979. Melkart appears in many of its images as a bright crater superimposed on the darker surface of Marius Regio.

Galileo became the first—and, as of 2026, the most recent—probe to image Melkart while orbiting Jupiter from December 1995 to September 2003. Galileo made a very close flyby of the area around Melkart during its G8 orbit in May 1997, allowing it to resolve details within the crater that are as small as 180 metres (590 ft) per pixel.[10]

The European Space Agency’s (ESA) Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice) was launched in April 2023 and is scheduled to arrive at Jupiter in July 2031.[11] In July 2034, Juice will enter a low orbit around Ganymede at an altitude of approximately 500 kilometres (310 mi).[12] The probe is expected to return high-resolution images of Melkart, helping planetary scientists better understand the evolution of Ganymede’s craters as they develop domes and modified by tectonic processes.

- ^ “Melkart”. Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Research Program. (Center Latitude: –9.86°, Center Longitude: 186.07°; Planetocentric, +West)

- ^ a b c Baby, Namitha Rose; Kenkmann, Thomas; Stephan, Katrin; Wagner, Roland; Hauber, Ernst (September 2024). “Ray and Halo Impact Craters on Ganymede: Fingerprint for Decoding Ganymede’s Crustal Structure”. Earth and Space Science. 11 (9). doi:10.1029/2024EA003541. e2024EA003541.

- ^ “Melqart Phoenician deity”. Britannica. 2026. Retrieved 10 February 2026.

- ^ “GANYMEDE – Melkart”. USGS. 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2026.

- ^ “Categories (Themes) for Naming Features on Planets and Satellites”. USGS. 2025. Retrieved 10 February 2026.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lucchetti, Alice; et al. (September 2023). “Geological, compositional and crystallinity analysis of the Melkart impact crater, Ganymede”. Icarus. 401. Bibcode:2023Icar..40115613L. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2023.115613. hdl:11577/3478872. 115613.

- ^ Ganymede Map Images Archived 2007-11-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ White, Oliver L.; Moore, Jeffrey M.; Schenk, Paul M.; Korycansky, Donald G.; Dombard, Andrew J.; Caussi, Martina L.; Singer, Kelsi N. (January 2025). “Large impact features on Ganymede and Callisto as revealed by geological mapping and morphometry”. Icarus. 426. arXiv:2403.13912. Bibcode:2025Icar..42616357W. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2024.116357. 116357.

- ^ a b “NIMS Observes Melkart Crater on Ganymede”. NASA/JPL. 26 March 1998. Archived from the original on 10 October 2025. Retrieved 11 December 2025.

- ^ Schenk, Paul, ed. (2012). Atlas of the Galilean Satellites. Cambridge University Press. p. 149. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511676468. ISBN 9780511676468.

- ^ “Juice Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer”. ESA. 2023. Retrieved 6 January 2026.

- ^ “Juice’s journey and Jupiter system tour”. ESA. 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2026.