Work

| ← Previous revision | Revision as of 15:58, 17 September 2025 | ||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

|

==Work==

|

==Work==

|

||

|

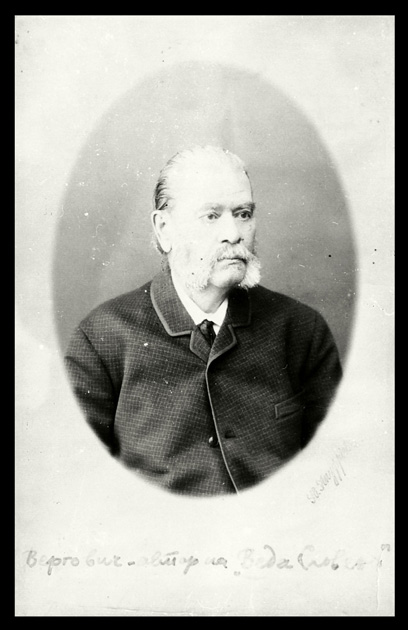

During the years he lived in Ottoman Empire, Verković proved to be a scientist in the field of folklore, ethnography and geography. He regularly supplied also coins from the area to Copenhagen, Paris, London and the [[Hermitage Museum|Hermitage]]. He еstablished intensive contacts with dozens of [[Bulgarian National Revival|Bulgarian national movement]] activists, becoming their associate. Verković noted in the foreword of ”Folk Songs” that the title was chosen because the locals identified themselves as Bulgarian.<ref>Ivo Banac, The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics, Cornell University Press, 1988, {{ISBN|0801494931}}, p. 310.</ref> After 1868 he became increasingly [[Bulgarophile]], disassociating from his given political mission. In addition, owing to his collector’s zeal, Verkovich saved a great number of old manuscripts, coins, objects of art, etc. His main and largest work is the mysticist{{sfn|Vojvodić|1979|p=237}} ”[[Veda Slovena]]” in two volumes, 1874 and 1881,<ref>Веда Словена и нашето време, Иван Богданов, Издател Университетско изд-во “Св. Климент Охридски”, 1991, стр. 17.</ref> which claimed to have contained “Bulgarian folk songs of the pre-historical and pre-Christian times, discovered in Thrace and Macedonia”. He despaired at the increasing distrust on his life’s work, ”Veda Slovena”, which many took to be a hoax. With the cooperation of government, he settled in [[Plovdiv]] from where he undertook in 1892–1893, two trips among the [[Pomaks]] in the Western [[Rhodopes]], trying to prove the authenticity of his Bulgarian folk songs collection, but the mission failed. He prepared a subsequent manuscript to publish also the third volume of ”Veda Slovena”. However, without financial support he

|

During the years he lived in Ottoman Empire, Verković proved to be a scientist in the field of folklore, ethnography and geography. He regularly supplied also coins from the area to Copenhagen, Paris, London and the [[Hermitage Museum|Hermitage]]. He еstablished intensive contacts with dozens of [[Bulgarian National Revival|Bulgarian national movement]] activists, becoming their associate. Verković noted in the foreword of ”Folk Songs” that the title was chosen because the locals identified themselves as Bulgarian.<ref>Ivo Banac, The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics, Cornell University Press, 1988, {{ISBN|0801494931}}, p. 310.</ref> After 1868 he became increasingly [[Bulgarophile]], disassociating from his given political mission. In addition, owing to his collector’s zeal, Verkovich saved a great number of old manuscripts, coins, objects of art, etc. His main and largest work is the mysticist{{sfn|Vojvodić|1979|p=237}} ”[[Veda Slovena]]” in two volumes, 1874 and 1881,<ref>Веда Словена и нашето време, Иван Богданов, Издател Университетско изд-во “Св. Климент Охридски”, 1991, стр. 17.</ref> which claimed to have contained “Bulgarian folk songs of the pre-historical and pre-Christian times, discovered in Thrace and Macedonia”. He despaired at the increasing distrust on his life’s work, ”Veda Slovena”, which many took to be a hoax. With the cooperation of government, he settled in [[Plovdiv]] from where he undertook in 1892–1893, two trips among the [[Pomaks]] in the Western [[Rhodopes]], trying to prove the authenticity of his Bulgarian folk songs collection, but the mission failed. He prepared a subsequent manuscript to publish also the third volume of ”Veda Slovena”. However, without financial support he in Sofia several months later.

|

||

|

==References==

|

==References==

|

||