Kingdom of Lao peoples

Candrapuri[1]: 77 or Candrapuri Sri Satta Naga[2]: 151 was a Laotian city-kingdom or muang located in the modern Vientiane region of Laos and Thailand.[2]: 151 [3] It existed prior to the formation of the Lan Xang Kingdom in the 14th century.[4]

A reference to the name Vientiane can be seen on a Vietnamese inscription of Duke Đỗ Anh Vũ, dated 1159 during the Khmer-Viet conflict. The inscription says that in 1135, Văn Đan (Vientiane), a vassal of Zhenla (Khmer Empire), invaded Nghe An, and was repelled by the Duke; the Duke led an army chased the invaders as far as Vũ Ôn? (unattested), and then returned with captives.[5]: 65

A few decades later, Phraya Chanthaburi (lit. ‘King of Chanthaburi‘; Vientiane), together with his elder brother Tao Gwa (ท้าวกวา) of Mueang Kaew Prakan (เมืองแกวประกัน; lit. ‘the Viet city of Prakan‘)—a polity commonly identified with Xiangkhouang (Muang Phuan)[6]—launched a large-scale military invasion of the Ngoenyang Kingdom of the Tai Yuan in 1171 CE. The invasion failed, however, as the Ngoenyang ruler Khun Chin sought military assistance from his nephews, the Chueang brothers. After successfully expelling the invaders, the younger Chueang marched eastward, annexed several polities, and eventually captured Muang Phuan.[7]: 9 [1]: 76–9 He then appointed his middle son, also named Chueang, as ruler of Muang Phuan, and his youngest son, Lao Pao (ลาวพาว), as ruler of Vientiane.[1]: 82–3

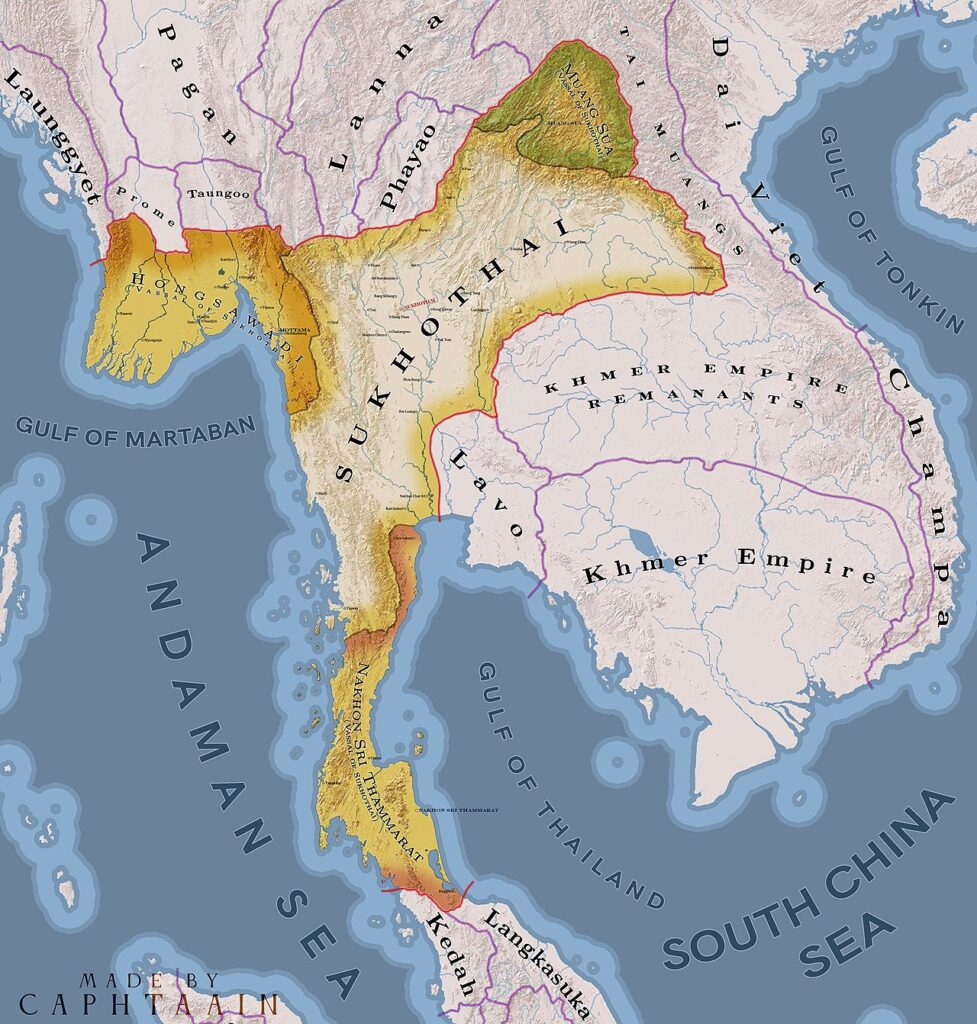

As another Laotian city-kingdom, the northern neighbor Muang Sua experienced a brief period of Angkorian suzerainty under Jayavarman VII from 1185 to 1191;[8]: 33 on this basis, Candrapuri, located between these two polities, may tentatively be understood as having experienced similar Angkorian influence. This interpretation is supported by the establishment of the Sanskrit–Lao Say Fong Inscription of Jayavarman VII K.368, dated to 1186, in the Vientiane area.[9]

However, the aforementioned presupposition has been challenged. No archaeological evidence of 12th century Bayon-style Angkorian architecture has been identified in the area, despite the inscription’s statement that Jayavarman VII ordered the construction of an ārogyasālā (hospital). Michel Lorrillard has argued that the inscription may have been relocated from Khu Ban Phanna (กู่บ้านพันนา; lit. ‘Ban Phanna Shrine‘) in the modern Sawang Daen Din District of Thailand—currently the northernmost known area with Angkorian architectural remains—possibly during the French colonial period, when cultural heritage was used to justify territorial claims and administrative control.[9] Lorrillard’s hypothesis is consistent with the findings of Anna Karlström’s 2009 survey.[10]

In the 13th century, during the reign of Ramkhamhaeng, Candrapuri or Vientiane was named as one of the polities under the Sukhothai Kingdom.[11] However, later scholarship suggests that Sukhothai may not have exercised direct control over Vientiane; rather, the relationship likely reflected a mandala-style political arrangement based on dynastic connections.[12] Vientiane continued to function as an autonomous city-kingdom until it was annexed in 1356 by Fa Ngum during his campaign to unite the Lao muangs into a single kingdom, Lan Xang.[4]

| Name | Reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| As a city-state under Gotapura during the Dvaravati period, spanning the 7th–11th centuries. | ||

| Vassal of Angkor during the reign of Suryavarman II (r. 1113–1145) | ||

| Phraya Chanthaburi | 1140s–1171 | Younger brother of Tao Gwa (ท้าวกวา) of Muang Phuan |

| Lao Pao (ลาวพาว) | 1172–1185? | Tai Yuan monarch from Ngoenyang. Youngest son of Chueang and Nang Am Paeng Chan Phong (นางอามแพงจันทน์ผง) |

| Buri Aoy Luay | Early 13th-c. | Enthroned as Phraya Chanthaburi Prasit Sakka Thewa (พญาจันทบุรีประสิทธิสักกะเทวะ)[3] |

- ^ a b c พงศาวดารเมืองเชียงแสน [Chronicle of Chiang Saen] (PDF) (in Thai). Suksapan. 1834. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2026.

- ^ a b Hartmann, John (1999). “Review of The Rama Jataka in Laos: A Study in the Phra Lak Phra Lam. Vol. I, Vol. II, by S. Sahai” (PDF). Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 150–3. Archived from the original on 7 February 2026.

- ^ a b Yutthaphong Matwises (4 August 2024). “บ้านเมืองอีสาน-สองฝั่งโขง ใน “อุรังคธาตุ” ตำนานพระธาตุพนม” [Northeastern towns and cities on both sides of the Mekong River in “Urankathathu”, the legend of Phra That Phanom]. www.silpa-mag.com (in Thai). Archived from the original on 2025-05-27. Retrieved 28 May 2025.

- ^ a b Singsong, Somkid (2 September 2019). “พรมแดนลาวสมัยเจ้าฟ้างุ่ม” [The border of Laos during the reign of King Fa Ngum]. Thang E-Shann (in Thai). 12 (1).

- ^ Taylor, K. W. (1995). Essays Into Vietnamese Pasts. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-501-71899-1.

- ^ Chisanupong Jamapanya (2 February 2024). ““ทุ่งไหหิน” มรดกโลกในลาว กับตำนาน “ทุ่งแห่งไหเหล้า” ของ “ขุนเจือง” ?” [The “Plain of Jars,” a World Heritage Site in Laos, and the legend of “The Plain of Wine Jars” of Khun Cheung?]. www.silpa-mag.com (in Thai). Retrieved 7 February 2026.

- ^ ตำนานพื้นเมืองเชียงใหม่ ฉบับ เชียงใหม่ 700 ปี [Chiang Mai Local Legends, 700th Anniversary Edition] (PDF) (in Thai). Chiang Mai: Chiang Mai Provincial Cultural Center, Chiang Mai Rajabhat University. ISBN 974-8150-62-3.

- ^ Ray, Nick (11 September 2009). Lonely Planet Vietnam Cambodia Laos & the Greater Mekong. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74179-174-7.

- ^ a b Songsiri, Walailak (15 February 2012). “อารยธรรมซายฟอง / Say Fong Civilization มรดกประวัติศาสตร์แบบอาณานิคม” [The Say Fong Civilization: A Colonial Historical Legacy]. Lek-Prapan Viriyahpant Foundation (in Thai). Retrieved 8 February 2026.

- ^ Karlström, Anna (2009). “Preserving Impermanace: The Creation of Heritage in Vientiane, Laos” (PDF). Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-2077-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2026.

- ^ Coedes, George (1965). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. Canberra: Australia National University Press. p. 205.

- ^ Siam Mapped: A history of the geo-body of a nation, by Thongchai Winichakul, University of Hawaii Press. 1994. p 163.