====Compositional means====

====Compositional means====

Following his early [[Johannes Brahms|Brahmsian]]–[[Richard Wagner|Wagnerian]] works,{{sfn|Shawn|2003|p=5–6}} Schoenberg stretched [[tonality]] past [[Key (music)|key]] centers in his [[String Quartets (Schoenberg)#String Quartet No. 2, Op. 10|String Quartet No. 2]], Op. 10 (1907–08) and dropped [[key signature]]s in ”[[The Book of the Hanging Gardens|Book of the Hanging Gardens]]”, Op. 15 (1908–09).{{sfn|Shawn|2003|p=9}} In ”Harmonielehre” (”Theory of Harmony”, 1910), he discussed what he later{{when|date=September 2025}}{{cn|date=September 2025}} called the “[[emancipation of the dissonance]]”, trying it in a spate of [[atonal]], [[Expressionism (music)|expressionist]]{{efn|Schoenberg didn’t like these labels.{{sfn|Shawn|2003|p=9}}}} works (1909–13):{{sfn|Shawn|2003|p=9–10, 63, 166–167, 131–141, 173–174}}

Following his early [[Johannes Brahms|Brahmsian]]–[[Richard Wagner|Wagnerian]] works,{{sfn|Shawn|2003|p=5–6}} Schoenberg stretched [[tonality]] past [[Key (music)|key]] centers in his [[String Quartets (Schoenberg)#String Quartet No. 2, Op. 10|String Quartet No. 2]], Op. 10 (1907–08) and dropped [[key signature]]s in ”[[The Book of the Hanging Gardens|Book of the Hanging Gardens]]”, Op. 15 (1908–09).{{sfn|Shawn|2003|p=9}} In ”Harmonielehre” (”Theory of Harmony”, 1910), he discussed what he later{{when|date=September 2025}}{{cn|date=September 2025}} called the “[[emancipation of the dissonance]]”, trying it in a spate of atonal, [[Expressionism (music)|expressionist]]{{efn|Schoenberg didn’t like these labels.{{sfn|Shawn|2003|p=9}}}} works (1909–13):{{sfn|Shawn|2003|p=9–10, 63, 166–167, 131–141, 173–174}}

*[[Drei Klavierstücke (Schoenberg)|Three Piano Pieces]], Op. 11 (1909, Feb.–Aug.){{efn|No. 3 was completed last and is particularly noted for these qualities.{{cn|date=September 2025}}}}

*[[Drei Klavierstücke (Schoenberg)|Three Piano Pieces]], Op. 11 (1909, Feb.–Aug.){{efn|No. 3 was completed last and is particularly noted for these qualities.{{cn|date=September 2025}}}}

*”[[Pierrot lunaire]]” (”Moonstruck Pierrot”), Op. 21 (1912, March–July)

*”[[Pierrot lunaire]]” (”Moonstruck Pierrot”), Op. 21 (1912, March–July)

Written during each year of this outpouring and completed at its end,<ref name=”GA18″/> ”Lucky Hand” spans a phase when Schoenberg was seeking new compositional means.{{sfn|Shawn|2003|p=9, 44, 92, 114, 151, 156–157, 173–174, 187}} He composed early sections spontaneously as in ”Erwartung”, using a quasi-[[stream of consciousness|stream-of-consciousness]] method to heighten the sense of [[psychological drama|psychodrama]].{{sfn|Shawn|2003|p=9, 94–102, 156–157}}{{efn|The Woman in ”Erwartung” lost in the woods may reflect Schoenberg’s own search.{{sfn|Shawn|2003|loc=102}}}} He carefully sketched later sections, like scene 3’s [[fugue|fugato]] opening, after ”Pierrot”, having reconciled atonality with familiar [[musical form]]s.{{sfn|Shawn|2003|loc=156–157}}

Written during each year of this outpouring and completed at its end,<ref name=”GA18″/> ”Lucky Hand” spans a phase when Schoenberg was seeking new compositional means.{{sfn|Shawn|2003|p=9, 44, 92, 114, 151, 156–157, 173–174, 187}} He composed early sections spontaneously as in ”Erwartung”, using a quasi-[[stream of consciousness|stream-of-consciousness]] method to heighten the sense of [[psychological drama|psychodrama]].{{sfn|Shawn|2003|p=9, 94–102, 156–157}}{{efn|The Woman in ”Erwartung” lost in the woods may reflect Schoenberg’s own search.{{sfn|Shawn|2003|loc=102}}}} He carefully sketched later sections, like scene 3’s [[fugue|fugato]] opening, after ”Pierrot”, having reconciled atonality with familiar [[musical form]]s.{{sfn|Shawn|2003|loc=156–157}}

====Influence of light music====

====Influence of light music====

| Die glückliche Hand | |

|---|---|

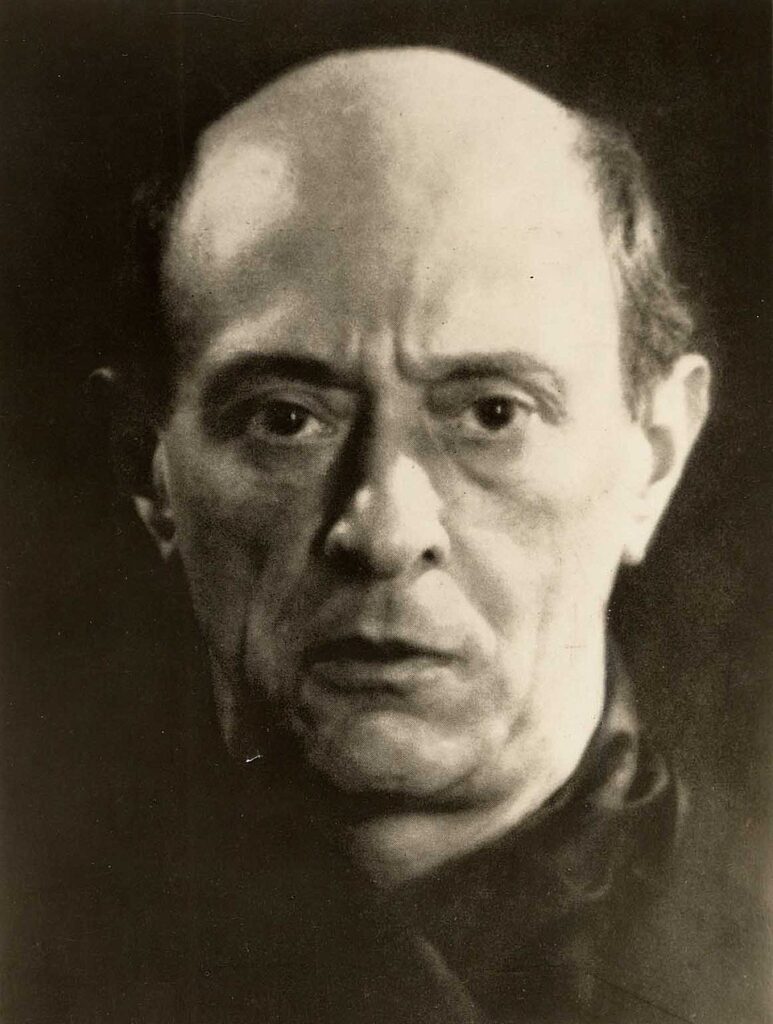

The composer in 1927 |

|

| Translation | The Lucky Hand |

| Language | German |

| Premiere |

24 October 1924 (1924-10-24)

|

Die glückliche Hand (The Lucky[a] Hand, 1909–1913), Op. 18, is a four-scene opera or “Drama with Music in One Act” by Arnold Schoenberg, who wrote the libretto. Like Erwartung (Expectation, 1909), it drew on Otto Weininger‘s book Sex and Character[1] and reflected Schoenberg’s own life, perhaps including his sense of artistic mission, audience reception, wife’s affair, or some combination. It conveys the idea that man repeats his mistakes.[2] The Vienna Volksoper premiered it on 24 October 1924.

Background and creation

Musical and sociocultural background

Die glückliche Hand (The Lucky Hand) is a four-scene opera or “Drama with Music in One Act” by Arnold Schoenberg.[4] It bridges late-Romantic Gesamtkunstwerk and experimental theater. He wrote it, including the libretto, during a turbulent, productive time in his life.[6]

Compositional means

Following his early Brahmsian–Wagnerian works, Schoenberg stretched tonality past key centers in his String Quartet No. 2, Op. 10 (1907–08) and dropped key signatures in Book of the Hanging Gardens, Op. 15 (1908–09). In Harmonielehre (Theory of Harmony, 1910), he discussed what he later[when?][citation needed] called the “emancipation of the dissonance“, trying it in a spate of atonal, expressionist[b] works (1909–13):

- Three Piano Pieces, Op. 11 (1909, Feb.–Aug.)[c]

- Five Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 16 (1909, May–Aug.)

- Die glückliche Hand (The Lucky Hand), Op. 18 (1909 Jun.–1913 Nov.)[10]

- Erwartung (Expectation), Op. 17 (1909, Aug.–Sept.)

- Six Little Piano Pieces, Op. 19 (1911, Feb.–June)

- Herzgewächse (Foliage of the Heart), Op. 20 (1911, Dec.)

- Pierrot lunaire (Moonstruck Pierrot), Op. 21 (1912, March–July)

Written during each year of this outpouring and completed at its end,[10] Lucky Hand spans a phase when Schoenberg was seeking new compositional means. He composed early sections spontaneously as in Erwartung, using a quasi-stream-of-consciousness method to heighten the sense of psychodrama.[d] He carefully sketched later sections, like scene 3’s fugato opening, after Pierrot, having reconciled atonality with familiar musical forms.

Influence of light music

Schoenberg lived in imperial Vienna, where artists turned inward amid the Habsburg monarchy‘s decline, and more progressive Berlin (1901–03, 1911–15, 1926–33). Schoenberg orchestrated many operettas as they flourished, and his works often use light music or its parody like composer Charles Ives, as in Lucky Hand’s brass band and laughter (scene 1, m. 26) and waltz-like episode (scene 3, m. 156). Working with monologists at the Überbrettl cabaret (1901–02) may have influenced his use of Sprechstimme (half speech, half song) in Lucky Hand.[e]

Surreal form

Lucky Hand, Erwartung, Pierrot, and parts of Moses und Aron (1923–37) may be considered dreamlike monodramas. Lucky Hand’s dreamer (the Man) is an artisan. But the work should be more abstract and surreal than a dream, Schoenberg told his publisher Emil Hertzka at Universal Edition.[22]

Many Viennese read psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams (1900) and, whether for guidance or gambling, more popular dream books, shaping cultural imagination.[f] In writing Lucky Hand, Schoenberg likely used these latter books’ schemes of color symbolism and possibly their numerology, which were marketed as having been drawn from ancient works like Artemidorus’ Oneirocritica.

Personal tragedy

Tragic love, recurring in Schoenberg’s work since Verklärte Nacht (1899), Pelleas und Melisande (1902–03), and Gurre-Lieder (1900–03, 1910–11), became personal the year before Lucky Hand.[2] In 1908, his first wife Mathilde, an educated pianist and composer Alexander von Zemlinsky‘s sister, had a romance with Fauvist and Expressionist painter Richard Gerstl, with whom they painted.

Gerstl died by suicide when she returned to Schoenberg and their two children at composer Anton Webern‘s urging. Schoenberg may have contemplated suicide himself and likely processed this trauma in Lucky Hand and other works from this time, with their anxious episodes, moods, or themes.[g] When Mathilde, often ill, died in 1923, he self-medicated and wrote a requiem text.

In 1924, Schoeberg married Gertrud Kolisch, his artistic collaborator (pseudonym: “Max Blonda”) and sister of the Kolisch Quartet‘s first violinist Rudolf Kolisch. She made a schematic of Lucky Hand’s “color crescendo” in 1930.[34]

Visual arts nexus

Schoenberg created portraits, abstract and naturalistic studies, caricatures, and set designs, including for Lucky Hand. In Alliance (Hands) (1910), he painted two mirrored forms in inseparable union.[37] He emphasized eyes rather than faces in portraits, as also in the stage directions for Erwartung and Lucky Hand. A 1910 solo exhibition of forty works at Hugo Heller‘s bookstore in Vienna[citation needed] was followed by group shows with Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Henri Rousseau, and Egon Schiele. Gustav Mahler was an anonymous patron.[h]

Schoenberg’s ideas about music and color came from dream books, German Romantics (who drew on older texts), musicians, and teaching, including Guido Adler‘s students, Webern and Egon Wellesz. His music inspired Kandinsky’s Impression III—Concert (1911) and a correspondence.[i] Citing Schoenberg’s Harmonielehre in On the Spiritual in Art (1911),[j] Kandinsky linked free use of sound and color as he moved toward abstraction.

Sketches suggest Schoenberg used dream books’ popular color symbolism in Lucky Hand (e.g., blue for sadness, green for hope, red for love or pain, yellow for jealousy, black for persecution, violet for comfort). In scene 3, the “color crescendo” syncs expressionist music, psychodrama, and colorful lighting, reflecting Romantic and modernist interest in synaesthesia and altered states of consciousness at the fin de siècle.[34][50][k] Kandinsky’s and Thomas de Hartmann’s Der gelbe Klang (The Yellow Sound, 1909; one of Kandinsky’s four “color dramas”, 1909–14) had a similar scene of only abstract action, sound, and stage lighting.[54]

Spiritual and sociopolitical context

Schoenberg’s œuvre explores Sisyphean longing: first more romantic (e.g., Hanging Gardens, Erwartung); then spiritual (e.g., Moses, Modern Psalm). These latter elements emerged in works like Lucky Hand, Jakobsleiter (1914–22, rev. 1944; on Jacob’s Ladder), and Der biblische Weg (1926–27), a Zionist play, as he sought to find meaning and ways forward.

Lucky Hand’s thwarted visionary (the Man), unattainable form (the Woman), and burning-bush-like, quasi-Greek chorus anticipate Moses. The sparse, allegorical libretto and detailed stage directions, rich in Symbolist imagery and suggestion, stress ineffability, realized via stylized gesture, lighting, scenery, and dissonant, cinematic music with word painting.[56][l]

Faint solo parts, hazy textures, and whispering (scene 1) may evoke the call and response of congregants and cantors from his mother’s Orthodox Jewish family.[m] The Woman’s withdrawal when the Man drinks from the goblet (scene 2) may suggest apophatic theology. Schoenberg’s innovative, “emancipated” musical expression (e.g., mm. 36–40 strings) may reflect his social otherness within tradition:

After Lucky Hand, he served in World War I, finished Four Orchestral Songs, Op. 22 (1913–16), and, while working on Jakobsleiter, continued to work toward what would become a new compositional means, the twelve-tone technique. Born after Jewish emancipation and baptized Lutheran (1898), he would’ve always been seen as Jewish and confronted antisemitism repeatedly. He broke with Kandinsky over the Jewish question in 1922 and fled the Nazis in 1933 to Paris. There he formally returned to Judaism, witnessed by artist Marc Chagall.

Drama and staging

Roles

- ein Mann (a Man), baritone

- ein Weib (a Woman), silent

- ein Herr (a Gentleman), silent

- Chorus, Sprechstimme

Synopsis

- The drama takes place in one act in which there are four scenes. It lasts about twenty minutes.

- The staging of Lucky Hand is complex, due to the range of scenic effects that must be combined with the use of colored lights. These also prompt the Man’s gestures, with hands, eyes, and body responding according to Schoenberg’s stage directions.

The drama represents an inescapable cycle of man’s plight as it starts and finishes with the male character struggling with the monster on his back. The male character sings about his love for a young woman (mime) but, despite this favor, she leaves him for a well-dressed gentleman (mime). He senses that she has left him and eventually, when she returns, he forgives her and his happiness returns. Again the woman retreats. The woman is seen later with the gentleman, and the male soloist implores the woman to stay with him but she escapes and kicks a rock at him. This rock turns into the monster that was originally seen on the man’s back. Thus, the drama ends where it began.

Instrumentation

The score calls for: piccolo, three flutes (3rd doubling on 2nd piccolo), three oboes, English horn, D clarinet, three clarinets (in B-flat and A), bass clarinet, three bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, four trombones, bass tuba, timpani, cymbals, bass drum, snare drum, tamtam, high and low bells, triangle, xylophone, glockenspiel, metal tubes, tambourine, hammer, harp, celesta, and strings. The piece also employs an offstage ensemble consisting of piccolo, E-flat clarinet, horn, trumpet, 3 trombones, triangle and cymbals.[64]

See also

Notes

- ^ Glücklich may be translated as lucky/fortunate/happy/favored; the title has appeared as The Lucky/Fortunate/Favored/Fated Hand or The Hand of Fate.[citation needed]

- ^ Schoenberg didn’t like these labels.

- ^ No. 3 was completed last and is particularly noted for these qualities.[citation needed]

- ^ The Woman in Erwartung lost in the woods may reflect Schoenberg’s own search.

- ^ Engelbert Humperdinck first used Sprechstimme in Königskinder (1897). Schoenberg asked that his 1899 musical setting of Hugo von Hofmannsthal‘s “Die Beiden” be “less sung than declaimed” and first used Sprechstimme in Gurre-Lieder.

- ^ See Losbuch.

- ^ Schoenberg’s son-in-law Felix Greissle tied Lucky Hand to this crisis.

- ^ Schoenberg’s recent music had been so poorly received that he took the stage only to keep his back to applause at the 1913 premiere of Gurre-Lieder. His Walking Self-Portrait (1911) may reflect his feelings.[42]

- ^ Kandinsky and Marc included Herzgewächse in Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider, 1912). Artist Paul Klee, also a musician, reviewed the Reiter and attended a 1913 Pierrot performance. Klee’s New Harmony (1936) has twelve mirrored colors, perhaps after Schoenberg.

- ^ Kandinsky partly translated and published Schoenberg’s Harmonielehre into Russian. He also cited others’ work (e.g., physician Franz Freudenberg, composer Alexander Scriabin, musicologist Leonid Sabaneyev, painters Claude Monet and the Fauves).

- ^ Op. 16/iii “Farben” (“Colors”) focused on orchestral timbre. Schoenberg’s 1915 home had rooms of distinct colors and moods, Alma Mahler recalled.

- ^ Music’s association with ineffability is continuous with strands of German Romanticism.

- ^ Anton Webern‘s choral music is comparatively clear and rhythmically straight.

References

- ^ Schiff, David (8 August 1999). “Schoenberg’s Cool Eye For the Erotic”. The New York Times

- ^ a b Biersdorfer, J. D. (22 May 2009). “Robert Edmond Jones’s Staging for ‘Die Glückliche Hand’ on Display at the Morgan”. The New York Times. Retrieved 9 April 2021. (subscription required)

- ^ Schoenberg, Arnold (1910). “The Lucky Hand (scene 2)”. Google Arts & Culture. Vienna: Arnold Schönberg Center. Retrieved 6 September 2025.

- ^ Shawn, Allen (2003). Arnold Schoenberg’s Journey. Harvard University Press. pp. 9–10, 44–47, 161. ISBN 978-0-674-01101-4.

- ^ a b https://archive2.schoenberg.at/compositions/werke_einzelansicht.php?werke_id=474

- ^ Krones 2003, 25–26, quoting Schoenberg: “Höchste Unwirklichkeit […] nicht wie ein Traum [… sondern] wie Akkorde […] als Spiel […] von Farben und Formen” (“highest unreality […] not like a dream [… rather] like chords … a game […] of colors and forms”). sfn error: no target: CITEREFKrones2003 (help)

- ^ a b Schönberg, Gertrud (1930). “Color Crescendo”. Google Arts & Culture. Berlin: Arnold Schönberg Center. Retrieved 5 September 2025.

- ^ Schoenberg, Arnold (1910). “Alliance (Hands)”. Google Arts & Culture. Vienna: Arnold Schönberg Center. Retrieved 5 September 2025.

- ^ Schoenberg, Arnold (1911). “Walking Self-Portrait”. Google Arts & Culture. Vienna: Arnold Schönberg Center. Retrieved 5 September 2025.

- ^ Facco, Enrico (2025). Understanding Non-Ordinary Mental Expressions and their Capabilities. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-0364-5309-1.

- ^ Krones, Hartmut (2004). “Farbe – Klang – Traum: Doppel- und Dreiecksbeziehungen durch Jahrhunderte”. Journal of the Arnold Schönberg Center. 2004, Der Maler Arnold Schönberg: the Painter (Bericht zum Symposium, 11.–13. September 2003). Arnold Schönberg Center: 25. ISBN 978-3-902012-09-8.

- ^ Krones 2003, 17–26, quoting Schoenberg’s desire for “kinematographische Wiedergabe” (“cinematographic reproduction”) sfnm error: no target: CITEREFKrones2003 (help); Shawn 2003, 3, 9–10, 24, 44, 50, 53–54, 102, 110–111, 157–170, 173–174, 198–199, 223, 226, 233–234.

- ^ Score with detailed stage directions (UE 1917)