* Solomon Crnojević (d. 1521); as the eldest son, he was sought by the [[Montenegrins]] from the [[Brda (Montenegro)|Highlands]] to govern a part of [[History of Montenegro#Struggle for maintaining independence (1496–1878)|Montenegro]], but the [[Republic of Venice]] did not allow it so as not to offend the [[Government of the classical Ottoman Empire|Ottoman authorities]]. He was married to Elisabetta and had no children. Solomon was killed in [[Kingdom of Hungary|Hungary]] in 1521 during the [[Hungarian–Ottoman War (1521–1526)|Hungarian–Ottoman War]].

* Solomon Crnojević (d. 1521); as the eldest son, he was sought by the [[Montenegrins]] from the [[Brda (Montenegro)|Highlands]] to govern a part of [[History of Montenegro#Struggle for maintaining independence (1496–1878)|Montenegro]], but the [[Republic of Venice]] did not allow it so as not to offend the [[Government of the classical Ottoman Empire|Ottoman authorities]]. He was married to Elisabetta and had no children. Solomon was killed in [[Kingdom of Hungary|Hungary]] in 1521 during the [[Hungarian–Ottoman War (1521–1526)|Hungarian–Ottoman War]].

His second marriage, in 1490, was to Isabetha (Elisabetta) [[Palazzo Erizzo a San Martino|Erizzo]] (d. 1522). She was the daughter of the Venetian nobleman and diplomat Antonio [[Francesco Erizzo#Background|Erizzo]] of the [[Venetian nobility#Others|Erizzo family]]. Antonio held numerous high-ranking state offices and eventually attained the honor of [[Procuratie|Procurator]], a position that often preceded election to the office of [[Doge of Venice|Doge]]. In 1478, he was one of five candidates for this highest honor in the Republic, although [[Giovanni Mocenigo]] was ultimately elected. At the time of his daughter’s marriage, Antonio served as [[Deputy governor|Vicedomino]] of [[Duchy of Ferrara|Ferrara]]. During their life in exile in [[Venice]] they lived in the [[Palazzo Zaguri]]. They had five children:

His second marriage, in 1490, was to Isabetha (Elisabetta) [[Palazzo Erizzo a San Martino|Erizzo]] (d. 1522). She was the daughter of the Venetian nobleman and diplomat Antonio [[Francesco Erizzo#Background|Erizzo]] of the [[Venetian nobility#Others|Erizzo family]]. Antonio held numerous high-ranking state offices and eventually attained the honor of [[Procuratie|Procurator]], a position that often preceded election to the office of [[Doge of Venice|Doge]]. In 1478, he was one of five candidates for this highest honor in the Republic, although [[Giovanni Mocenigo]] was ultimately elected. At the time of his daughter’s marriage, Antonio served as [[Deputy governor|Vicedomino]] of [[Duchy of Ferrara|Ferrara]]. During their life in exile in [[Venice]] they lived in the [[Palazzo Zaguri]]. They had five children:

* Konstantin (Constantine) Crnojević (1491-1536); he was married to Maria [[Contarini family|Contarini]], daughter of [[Giovanni Matteo Contarini]]. They lived in [[Venice]] and had a son Ivan (Giovanni), with written records of their descendants existing up until the second half of the 17th century, when the family line became extinct.

* Konstantin (Constantine) Crnojević (1491-1536); he was married to Maria [[Contarini family|Contarini]], daughter of [[Giovanni Matteo Contarini]]. They lived in [[Venice]] and had a son Ivan (Giovanni), with written records of their descendants existing up until the second half of the 17th century, when the family line became extinct.

Serbian medieval Lord of Zeta

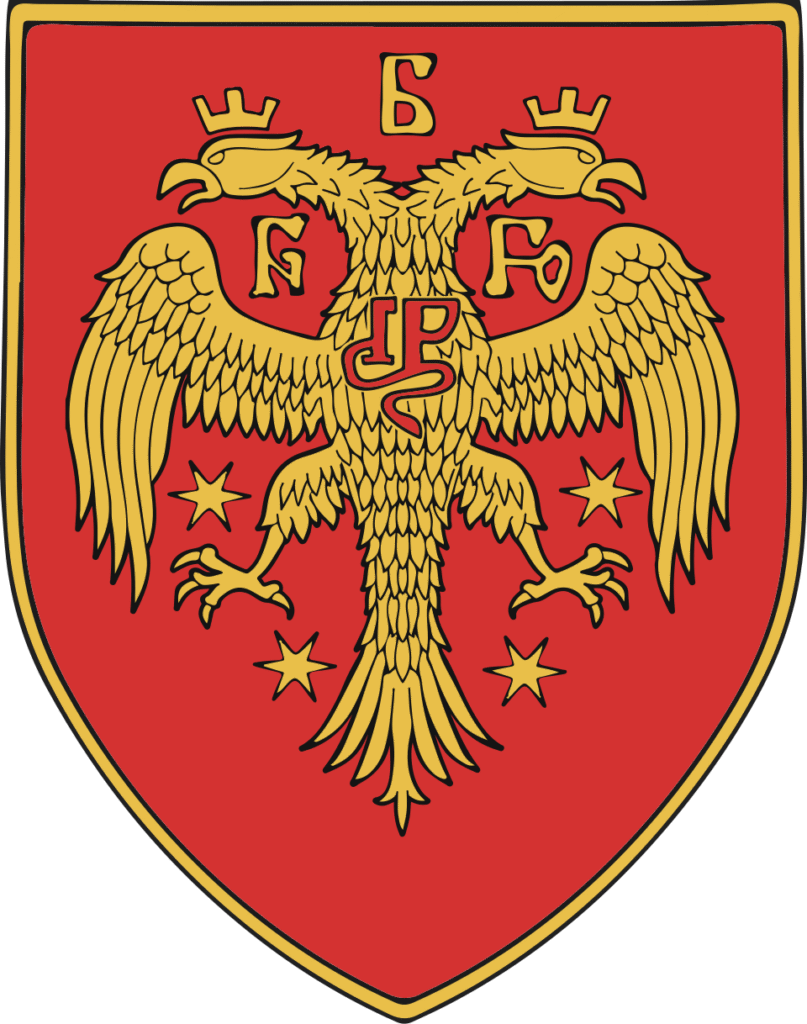

Đurađ Crnojević (Serbian Cyrillic: Ђурађ Црноjeвић, Church Slavonic: Гюргь Цьрноевыкь; d. 1514) was the last Serbian medieval Lord of Zeta[1] between 1490 and 1496, from the Crnojević dynasty.

Early life and ancestry

Born into the House of Crnojević, rulers of the Principality of Zeta, he was the eldest son of Ivan Crnojević and his wife, Voisava Arianiti, member of the Albanian nobility.

His grandmother from his father’s side, Mara Kastrioti, was a sister of Skanderbeg. This made Đurađ Skanderbeg’s grandnephew and through his mother he was the grandson of Gjergj Arianiti, member of the Arianiti family, and nephew of the Scanderbeg’s wife, Andronika Kastrioti, herself a member of the Arianiti family.

First Serbian printing house

He was the founder of the first Serbian printing house.[2] Crnojević styled himself “Duke of Zeta”. He was well known by his great education, knowledge of astronomy, geometry and other sciences.

Life and reign

During his short-term reign he became famous for making efforts to spread the cultural heritage rather than for his political successes. The Ottomans made him leave Zeta in 1496. His brother Stefan inherited his position of the Lord of Zeta. In 1497 Venetians imprisoned Đurađ for some time, accusing him to be an Ottoman collaborator. He again spent some time in Venetian prison in period between 30 July and 25 October 1498. This time the Ottomans insisted that Venetians should put him into prison, which they eventually did. On 22 October 1499 he wrote his testament, which is considered as valuable literature work of its time.

In the spring of 1500 Đurađ Crnojević came to Scutari, based on the invitation of Feriz Beg who instructed Crnojević to travel to Istanbul. In Istanbul Crnojević officially ceded his possessions to the sultan who granted him an estate (timar) in Anatolia to govern it as its sipahi.

Although he was removed from the historical scene, his books remained as a great contribution to the Serbian culture. With the help of Hieromonk Makarije he printed five books of importance to the Serbian cultural heritage: Oktoih prvoglasnik (1493/94), Oktoih petoglasnik (1494), Psaltir s posljedovanjem (1495), Trebnik (prayer book; 1495/96), and Četvorojevanđelje (probably 1496).

Marriages and children

Đurađ Crnojević was married twice. His first wife was Yela Thopia, daughter of Karl Muzaka Thopia. They had one son:

His second marriage, in 1490, was to Isabetha (Elisabetta) Erizzo (d. 1522). She was the daughter of the Venetian nobleman and diplomat Antonio Erizzo of the San Moisè branch of the Erizzo family. Antonio held numerous high-ranking state offices and eventually attained the honor of Procurator, a position that often preceded election to the office of Doge. In 1478, he was one of five candidates for this highest honor in the Republic, although Giovanni Mocenigo was ultimately elected. At the time of his daughter’s marriage, Antonio served as Vicedomino of Ferrara. During their life in exile in Venice they lived in the Palazzo Zaguri. They had five children:

The Testament of Đurađ Crnojević

A notarial facsimile of the official procedure for the proclamation of Đurađ Crnojević’s last will is preserved (Appendix of the autograph). The document, copied in 103 densely written lines by the ducal notary, constitutes the full testament. It is composed of three distinct, yet legally closely related, parts that were created over a period of eighteen years.

On 22 October 1499, Đurađ Crnojević personally wrote his last will in the Serbian language using the Cyrillic script. As translations from all foreign languages were required in Venice, a statement was added by the late Stefano Pasquale, dated 20 April 1514 in the office of the Gastaldo, confirming that the text of the testament’s translation “from the Slavic language and script,” which was presented to him, was indeed authentic and personally written by Đurađ Crnojević “faithfully word for word… without altering or distorting the meaning of any matter.” This statement constitutes the first part of the complete document. It appears that the translation had originally been prepared as early as 1503.

Pasquale’s Italian translation was later copied in 1517 by the ducal notary Jacopo Grasolari and incorporated into the full document, granting it official legal force and formally recognizing Đurađ Crnojević’s last will as a valid testament. This constitutes the second part of the document.

The third part consists of the procedural introduction and concluding text in Latin, which outlines the process by which the testament was officially proclaimed. The Venetian procedure involved six stages: initiation of the process, translation from the foreign language into Italian, opinions from the competent forums, a positive decision by the Council under the Doge’s presidency, drafting of the complete official text by the ducal notary, and the personal signatures of the Doge, witnesses, and notary.

The procedure was initiated by the person entitled to the declaration of the last will, who in this case was Đurađ Crnojević’s widow Elisabetta, designated as the universal heir. It appears that she had already begun the process in 1503 and at that time provided the original testament to Stefano Pasquale for translation, which he completed. Upon the summons of the Gastaldo in 1514, he confirmed that it was indeed his faithful translation. Evidence of a possible translation as early as 1503 is recorded in the Diary of Marino Sanuto, who notes on 26 November 1503 that the daughter of Antonio Erizzo personally appeared before the Venetian Senate to request clarification regarding her maintenance.

The procedure was resumed eleven years later in 1514 and was only completed in 1517. The Gastaldi accepted the earlier Italian translation by Pasquale, and it remained part of the final document, although the procedural Latin text explicitly states several times that a Latin translation was also required, which was to be prepared by an official of the Lower Chancery.

The procedure concluded with an order from the Minor and Major Councils directing all judicial authorities in Venetian territory to recognize the testament as a fully valid document. Monetary fines of 10 liras were established for non-compliance, and the official notarial text was prepared and certified, culminating with the signatures of the Doge Leonardo Loredan and the ducal notary and chancellor, Jacopo Grasolari.

On the official notarial document of the testament, the first witness was the Venetian Doge Leonardo Loredan himself, and the other two witnesses were the councilors Paolo Trevisan and Nicola Cornaro. The procedure was only completed at the beginning of January 1517, and the testament was declared valid and given full legal force.[10][11]

Family tree

| Ancestry of Đurađ Crnojević |

|---|