}}

}}

”'”Mind or Instinct: An Inquiry Concerning the Manifestation of Mind by the Lower Orders of Animals””’ is an 1843 essay by American anthropologist [[Lewis H. Morgan]] that argues animals and humans share the same intellectual principle, differing only in degree. Written when Morgan was 25 and recently admitted to the New York bar, it drew on his rural upbringing, classical studies, and interest in [[natural history]]. Published under the pseudonym “Aquarius” in ”[[The Knickerbocker]]”, the essay addresses issues in [[comparative psychology]] and the [[philosophy of mind]], challenging the prevailing view that [[animal behaviour|animal behavior]] is guided by instinct alone. Morgan discusses [[animal memory]], abstraction, imagination, and judgment, drawing on examples from natural history, anecdotal reports, and classical authorities, and concludes that continuity of mind across species has moral implications for the treatment of animals.

”'”Mind or Instinct: An Inquiry Concerning the Manifestation of Mind by the Lower Orders of Animals””’ is an 1843 essay by American anthropologist [[Lewis H. Morgan]] that argues animals and humans share the same intellectual principle, differing only in degree. Written when Morgan was 25 and recently admitted to the New York bar, it drew on his rural upbringing, classical studies, and interest in [[natural history]]. Published under the pseudonym “Aquarius” in ”[[The Knickerbocker]]”, the essay addresses issues in [[comparative psychology]] and the [[philosophy of mind]], challenging the prevailing view that [[animal behaviour|animal behavior]] is guided by instinct alone. Morgan discusses [[animal memory]], abstraction, imagination, and , drawing on examples from natural history, anecdotal reports, and classical authorities, and concludes that continuity of mind across species has moral implications for the treatment of animals.

Scholars have described the essay as an early indication of Morgan’s intellectual development, foreshadowing his anthropological theories of human progress and his use of comparative methods. It has also been compared with the early writings of [[Charles Darwin]] as part of a wider nineteenth-century debate about [[animal intelligence]].

Scholars have described the essay as an early indication of Morgan’s intellectual development, foreshadowing his anthropological theories of human progress and his use of comparative methods. It has also been compared with the early writings of [[Charles Darwin]] as part of a wider nineteenth-century debate about [[animal intelligence]].

Morgan begins with [[animal memory]], citing examples of animals retaining and recalling experiences across time and place. He refers to bees returning to a food source months later, elephants recognizing former keepers after many years, and pigeons navigating back to their lofts. Such cases, he suggests, show that “instinct remembers”, and that the faculty is essentially identical with [[human memory]].<ref name=”Morgan November 1843″ />

Morgan begins with [[animal memory]], citing examples of animals retaining and recalling experiences across time and place. He refers to bees returning to a food source months later, elephants recognizing former keepers after many years, and pigeons navigating back to their lofts. Such cases, he suggests, show that “instinct remembers”, and that the faculty is essentially identical with [[human memory]].<ref name=”Morgan November 1843″ />

Turning to abstraction, Morgan argues that animals are able to compare and select among alternatives. His most detailed example concerns beavers, which he describes as weighing factors such as depth, width, and current of streams, the availability of trees and clay, and the proximity of food when choosing a site for a dam. The coordinated labour of beavers in felling trees, transporting materials, and adjusting water flow is presented as evidence of judgment and foresight. He extends this argument to foxes, birds, and other species whose choices of habitat and behaviour suggest the ability to generalize from experience.<ref name=”Morgan November 1843″ />

Turning to abstraction, Morgan argues that animals are able to compare and select among alternatives. His most detailed example concerns beavers, which he describes as weighing factors such as depth, width, and current of streams, the availability of trees and clay, and the proximity of food when choosing a site for a dam. The coordinated labour of beavers in felling trees, transporting materials, and adjusting water flow is presented as evidence of judgment and foresight. He extends this argument to foxes, birds, and other species whose choices of habitat and behaviour suggest the ability to generalize from experience.<ref name=”Morgan November 1843″ />

On imagination, Morgan acknowledges the difficulty of discerning an inner faculty from outward actions, but he interprets playful behaviour in young animals, apparent dreaming in dogs, and migratory restlessness in birds as signs of imaginative activity. He also notes parallels between human and animal responses to scenery and climate, which he takes as evidence of shared imaginative sensibility.<ref name=”Morgan November 1843″ />

On imagination, Morgan acknowledges the difficulty of discerning an inner faculty from outward actions, but he interprets playful behaviour in young animals, apparent dreaming in dogs, and migratory restlessness in birds as signs of imaginative activity. He also notes parallels between human and animal responses to scenery and climate, which he takes as evidence of shared imaginative sensibility.<ref name=”Morgan November 1843″ />

The final section addresses reason or judgment. Morgan recounts anecdotes of dogs seeking medical help, foxes using deception, and birds modifying behaviour in response to new circumstances. He also describes cases of cooperative labour among ants, marmots, and beavers, which he interprets as evidence of planning and division of labour. Training and domestication further illustrate, in his view, that animals learn by association and motivation rather than by mechanical impulse. Drawing on both classical authorities and natural history, Morgan concludes that the works of animals—whether nests, webs, or dams—show intelligence applied to practical ends. He rejects instinct as a separate, mysterious force, proposing instead that a single thinking principle pervades all living beings. This principle, he argues, forms a continuous scale from the lowest animals to humans, who once stood on the same level before advancing through the cultivation of reason.<ref name=”Morgan December 1843″>{{cite journal |last=Morgan |first=Lewis H. |author-link=Lewis H. Morgan |date=December 1843 |title=Mind or Instinct: An Inquiry Concerning the Manifestation of Mind by the Lower Orders of Animals |url=https://www.gutenberg.org/files/44591/44591-h/44591-h.htm#MIND_OR_INSTINCT |journal=The Knickerbocker |volume=22 |issue=6 |pages=507–516}}</ref>

The final section addresses . Morgan recounts anecdotes of dogs seeking medical help, foxes using deception, and birds modifying behaviour in response to new circumstances. He also describes cases of cooperative labour among ants, marmots, and beavers, which he interprets as evidence of planning and division of labour. Training and domestication further illustrate, in his view, that animals learn by association and motivation rather than by mechanical impulse. Drawing on both classical authorities and natural history, Morgan concludes that the works of animals—whether nests, webs, or dams—show intelligence applied to practical ends. He rejects instinct as a separate, mysterious force, proposing instead that a single thinking principle pervades all living beings. This principle, he argues, forms a continuous scale from the lowest animals to humans, who once stood on the same level before advancing through the cultivation of reason.<ref name=”Morgan December 1843″>{{cite journal |last=Morgan |first=Lewis H. |author-link=Lewis H. Morgan |date=December 1843 |title=Mind or Instinct: An Inquiry Concerning the Manifestation of Mind by the Lower Orders of Animals |url=https://www.gutenberg.org/files/44591/44591-h/44591-h.htm#MIND_OR_INSTINCT |journal=The Knickerbocker |volume=22 |issue=6 |pages=507–516}}</ref>

In closing, Morgan reflects on the ethical implications of this continuity. If animals share the same intellectual principle as humans, he suggests, their happiness is equally intended by the Creator. He remarks on the cruelty with which humans treat other species, including slaughter and sport hunting, and argues that a more enlightened moral sense would lead people to abstain from unnecessary harm. He even raises the possibility that humans might one day dispense with animal food altogether if able to live without it, framing compassion toward animals as consistent with divine design.<ref name=”Morgan December 1843″ />

In closing, Morgan reflects on the ethical implications of this continuity. If animals share the same intellectual principle as humans, he suggests, their happiness is equally intended by the Creator. He remarks on the cruelty with which humans treat other species, including slaughter and sport hunting, and argues that a more enlightened moral sense would lead people to abstain from unnecessary harm. He even raises the possibility that humans might one day dispense with animal food altogether if able to live without it, framing compassion toward animals as consistent with divine design.<ref name=”Morgan December 1843″ />

== Further writings on animal psychology ==

== Further writings on animal psychology ==

1843 essay by Lewis H. Morgan

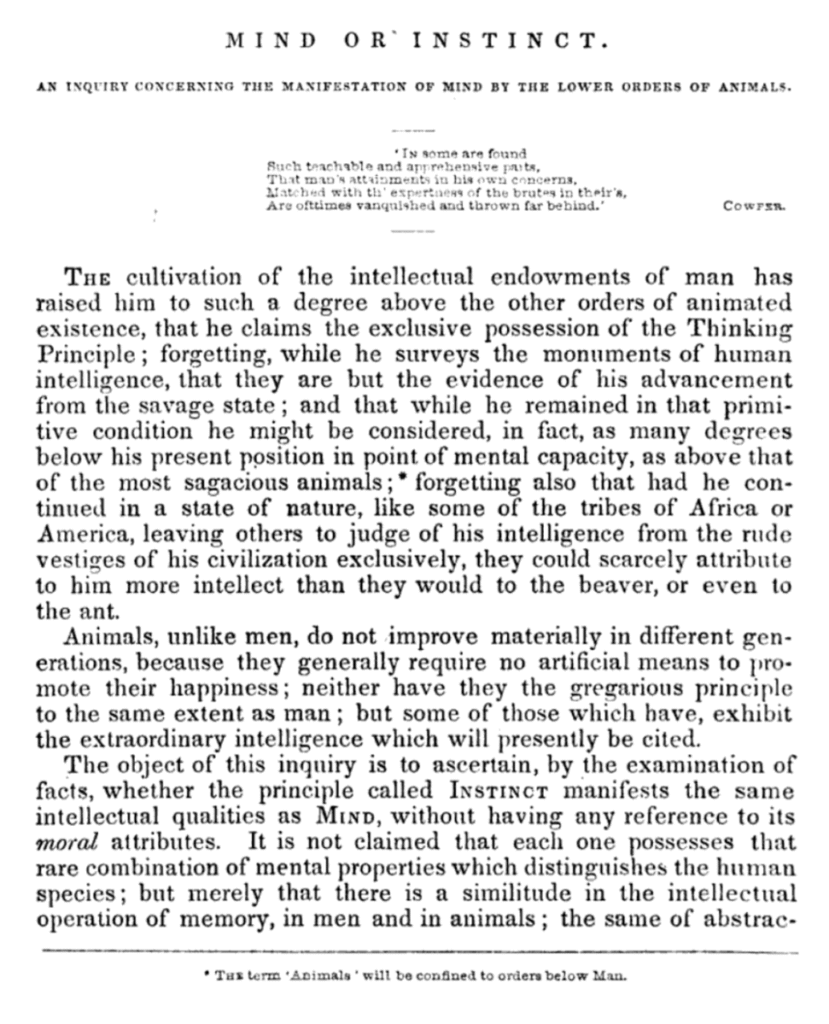

“Mind or Instinct: An Inquiry Concerning the Manifestation of Mind by the Lower Orders of Animals” is an 1843 essay by American anthropologist Lewis H. Morgan that argues animals and humans share the same intellectual principle, differing only in degree. Written when Morgan was 25 and recently admitted to the New York bar, it drew on his rural upbringing, classical studies, and interest in natural history. Published under the pseudonym “Aquarius” in The Knickerbocker, the essay addresses issues in comparative psychology and the philosophy of mind, challenging the prevailing view that animal behavior is guided by instinct alone. Morgan discusses animal memory, abstraction, imagination, and reasoning, drawing on examples from natural history, anecdotal reports, and classical authorities, and concludes that continuity of mind across species has moral implications for the treatment of animals.

Scholars have described the essay as an early indication of Morgan’s intellectual development, foreshadowing his anthropological theories of human progress and his use of comparative methods. It has also been compared with the early writings of Charles Darwin as part of a wider nineteenth-century debate about animal intelligence.

Lewis H. Morgan was born in 1818 on a farm near Aurora, New York. He studied classics at Cayuga Academy and then at Union College (1838–40) before returning to Aurora to read law. Alongside his legal training he developed wide interests in classics, natural history, geology, and social reform, and delivered public lectures on subjects ranging from temperance to ancient Greece. He was admitted to the New York bar in 1842.[1]

At 25, Morgan wrote “Mind or Instinct”, one of his earliest published works. Conceived as an effort to show that animals adjust to their environments through thought rather than mere instinct, the essay drew on Buffon‘s Natural History, farmers’ almanacs, and neighbors’ anecdotes to assemble examples of animals exhibiting memory, judgment, and deliberation.[2]

Both parts of the essay open with the same lines from the poet William Cowper, who suggested that human attainments are sometimes outdone by the “expertness” of animals. Gillian Feeley-Harnik observes that this choice of epigraph reflected the cultural and moral context in which Morgan was writing, one that regarded human and animal capacities as closely related. She argues that his rural background, steeped in agricultural practice and debates about the “improvement” of animals, together with his immersion in popular natural history, encouraged him to frame the essay in terms of progressive development and collective adaptation. In his interpretation, animal societies such as beavers offered evidence of gradual advancement and continuity across species, themes that anticipated his later zoological and anthropological work.[3]

In “Mind or Instinct”, Morgan considers whether instinct and mind are distinct faculties or whether they reflect the same intellectual principle. He identifies four areas of inquiry, memory, abstraction, imagination, and reason, and argues that animals display each of these capacities to varying degrees, differing from humans in degree rather than in kind.[4]

Morgan begins with animal memory, citing examples of animals retaining and recalling experiences across time and place. He refers to bees returning to a food source months later, elephants recognizing former keepers after many years, and pigeons navigating back to their lofts. Such cases, he suggests, show that “instinct remembers”, and that the faculty is essentially identical with human memory.[4]

Turning to abstraction, Morgan argues that animals are able to compare and select among alternatives. His most detailed example concerns beavers, which he describes as weighing factors such as depth, width, and current of streams, the availability of trees and clay, and the proximity of food when choosing a site for a dam. The coordinated labour of beavers in felling trees, transporting materials, and adjusting water flow is presented as evidence of judgment and foresight. He extends this argument to foxes, birds, and other species whose choices of habitat and behaviour suggest the ability to generalize from experience.[4]

On imagination, Morgan acknowledges the difficulty of discerning an inner faculty from outward actions, but he interprets playful behaviour in young animals, apparent dreaming in dogs, and migratory restlessness in birds as signs of imaginative activity. He also notes parallels between human and animal responses to scenery and climate, which he takes as evidence of shared imaginative sensibility.[4]

The final section addresses animal reasoning. Morgan recounts anecdotes of dogs seeking medical help, foxes using deception, and birds modifying behaviour in response to new circumstances. He also describes cases of cooperative labour among ants, marmots, and beavers, which he interprets as evidence of planning and division of labour. Training and domestication further illustrate, in his view, that animals learn by association and motivation rather than by mechanical impulse. Drawing on both classical authorities and natural history, Morgan concludes that the works of animals—whether nests, webs, or dams—show intelligence applied to practical ends. He rejects instinct as a separate, mysterious force, proposing instead that a single thinking principle pervades all living beings. This principle, he argues, forms a continuous scale from the lowest animals to humans, who once stood on the same level before advancing through the cultivation of reason.[5]

In closing, Morgan reflects on the ethical implications of this continuity. If animals share the same intellectual principle as humans, he suggests, their happiness is equally intended by the Creator. He remarks on the cruelty with which humans treat other species, including slaughter and sport hunting, and argues that a more enlightened moral sense would lead people to abstain from unnecessary harm. He even raises the possibility that humans might one day dispense with animal food altogether if able to live without it, framing compassion toward animals as consistent with divine design.[5]

Further writings on animal psychology

[edit]

Morgan returned to the themes of “Mind or Instinct” in several later works. In an unpublished 1857 essay titled “Animal Psychology”, he again rejected instinct as a distinct faculty, describing it as a “supernatural installation” that hindered inquiry, and argued instead that a common “thinking principle” extended across species. He continued this line of argument in The American Beaver and His Works (1868), which used field observations in Michigan to demonstrate that beaver societies exhibited adaptation, memory, imagination, and gradual improvement, qualities he had earlier attributed to animals in “Mind or Instinct” essay. These continuities extended into his later anthropological works such as Ancient Society (1877), where the idea of a “scale of mind” linking animals and humans underpinned his broader comparative method.[6]

Reception and legacy

[edit]

Carl Resek argues that the significance of “Mind or Instinct” lies less in its immediate impact than in what it reveals about Morgan’s intellectual development. He identifies it as Morgan’s first attempt to outline a rational history of animals, foreshadowing his later anthropological theories of human progress. By attributing a “thinking principle” to animals and rejecting a strict divide between instinct and reason, Resek maintains that Morgan shows an early concern with continuity between human and non-human intelligence. Against metaphysical claims that animals lacked such a faculty, Morgan contends that humans themselves had advanced from similar mental beginnings. His conclusions echoed contemporary ideas, including Charles Darwin‘s youthful notes on animals, but he expressed them in his own way, presenting animals as capable of reasoned adaptation rather than driven solely by instinct. Resek interprets the work as youthful but revealing, a formative attempt to grapple with ideas that would shape Morgan’s later scholarship.[2]

Thomas Trautmann likewise describes the essay as Morgan’s first statement of the “scale of mind” that links animals and humans in a single gradation. He notes that it already contains elements of Morgan’s later anthropology: a comparative method, the idea of stages of savagery and civilization, and a unified scale of intelligence across species. Trautmann also emphasizes that Morgan’s views on animal psychology remained largely unchanged throughout his career, even after the appearance of Darwin’s works.[7]

Gillian Feeley-Harnik, in her chapter on Morgan in America’s Darwin: Darwinian Theory and U.S. Literary Culture (2014), situates “Mind or Instinct” within the wider nineteenth-century debate about animal intelligence. She argues that Morgan rejects instinct as an explanatory category and instead proposes a single scale of intelligence uniting humans with other animals. Feeley-Harnik compares his conclusions with Darwin’s contemporary notebook entries on animal memory, emotions, and suffering, noting that while Darwin framed the issue in terms of descent and common ancestry, Morgan emphasized progressive improvement through the cultivation of reason. She adds that although Darwin’s writings became central to comparative psychology, Morgan’s early contribution was largely overlooked by later figures such as George Romanes and William James.[8]

Publication history

[edit]

“Mind or Instinct” was signed “Aquarius. October 1843” and published in two parts in The Knickerbocker, a New York literary magazine. The first installment appeared in the November 1843 issue and the second in the December 1843 issue.[6]

- ^ Feeley-Harnik, Gillian (2018), “Morgan, Lewis Henry (1818–81)”, The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–6, doi:10.1002/9781118924396.wbiea2056, ISBN 978-1-118-92439-6, retrieved September 16, 2025

- ^ a b Resek, Carl (1960). Lewis Henry Morgan, American Scholar. University of Chicago Press. pp. 18–19.

- ^ Feeley-Harnik, Gillian (2014). Gianquitto, Tina; Fisher, Lydia; Anelli, Carol (eds.). America’s Darwin: Darwinian Theory and U.S. Literary Culture. University of Georgia Press. pp. 265–270.

- ^ a b c d Morgan, Lewis H. (November 1843). “Mind or Instinct: An Inquiry Concerning the Manifestation of Mind by the Lower Orders of Animals”. The Knickerbocker. 22 (5): 414–420.

- ^ a b Morgan, Lewis H. (December 1843). “Mind or Instinct: An Inquiry Concerning the Manifestation of Mind by the Lower Orders of Animals”. The Knickerbocker. 22 (6): 507–516.

- ^ a b Feeley-Harnik, Gillian (2021). “‘The Mystery of Life in All Its Forms’: Religious Dimensions of Culture in Early American Anthropology”. In Mizruchi, Susan L. (ed.). Religion and Cultural Studies. Princeton University Press. pp. 140–191. ISBN 978-0-691-22404-6. Retrieved September 17, 2025.

- ^ Trautmann, Thomas R. (1987). Lewis Henry Morgan and the Invention of Kinship. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 18–35.

- ^ Feeley-Harnik, Gillian (2014). “Bodies, Words, and Works: Charles Darwin and Lewis Henry Morgan on Human-Animal Relations”. In Gianquitto, Tina; Fisher, Lydia (eds.). America’s Darwin: Darwinian Theory and U.S. Literary Culture. University of Georgia Press. pp. 265–301.