}}

}}

The ”’Moba”’, who go by ”’Bimoba”’, also be known as Bimawba, B’Moba, or Moab, is an ethnic group that is primarily located in northern region in both Ghana and Togo. They speak a [[Niger–Congo languages|Niger-Congo language]] and is part of the Gurma cultural and linguistic group. There is an estimated 200,00 people that identify themselves as Bimoba<ref>{{Cite book |title=Africana: the encyclopedia of the African and African American experience |date=2005 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-517055-9 |editor-last=Appiah |editor-first=Anthony |edition=2nd |volume=3 |location=Oxford; New York |pages=426 |editor-last2=Gates |editor-first2=Henry Louis}}</ref> and about 481,500 people in northern Togo.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.ethnologue.com/language/mfq | title=Moba }}</ref> This group lives in the middle of the Dapaon territory. Who a lineage-focused paternal group perform with ceremonials that reflect their spiritual line.<ref name=”:22″>{{Cite journal |last=Kreamer |first=Christine Mullen |date=1986 |title=THE ART AND RITUAL OF THE MOBA OF NORTHERN TOGO |url=https://www.proquest.com/docview/303480611?pq-origsite=primo&searchKeywords=Kreamer%20%20C.%20M.%20(1986).%20The%20Art%20And%20Ritual%20Of%20The%20Moba%20Of%20Northern%20Togo&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses |journal=Indiana University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses |pages=p, g, 52 |isbn=9798206289527}}</ref>

The ”’Moba”’, who go by ”’Bimoba”’, also be known as Bimawba, B’Moba, or Moab, is an ethnic group that is primarily located in northern region in both Ghana and Togo. They speak a [[Niger–Congo languages|Niger-Congo language]] and is part of the Gurma cultural and linguistic group. There is an estimated 200,00 people that identify themselves as Bimoba<ref>{{Cite book |title=Africana: the encyclopedia of the African and African American experience |date=2005 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-517055-9 |editor-last=Appiah |editor-first=Anthony |edition=2nd |volume=3 |location=Oxford; New York |pages=426 |editor-last2=Gates |editor-first2=Henry Louis}}</ref> and about 481,500 people in northern Togo.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.ethnologue.com/language/mfq | title=Moba }}</ref> This group lives in the middle of the Dapaon territory. Who a lineage-focused paternal group perform with ceremonials that reflect their spiritual line.<ref name=”:22″>{{Cite journal |last=Kreamer |first=Christine Mullen |date=1986 |title=THE ART AND RITUAL OF THE MOBA OF NORTHERN TOGO |url=https://www.proquest.com/docview/303480611?pq-origsite=primo&searchKeywords=Kreamer%20%20C.%20M.%20(1986).%20The%20Art%20And%20Ritual%20Of%20The%20Moba%20Of%20Northern%20Togo&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses |journal=Indiana University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses |pages=p, g, 52 |isbn=9798206289527}}</ref>

The Moba held a clan-based society<ref name=”pdf3″>{{cite book |author1=J.J. Meij |url=https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/access/item%3A2923390/view |title=Testing Life history theory in a contemporary African population. Chapter 3 – The Bimoba: the people of Yennu |author2=D. van Bodegom |author3=D. Baya Laar |publisher=Thesis Leiden University, the Netherlands |year=2007}}</ref> that focus on their relationship with their ancestors.<ref name=”:32″>{{Cite book |last=Bourdier |first=Jean-Paul |title=Vernacular architecture of West Africa: a world in dwelling |last2=Trinh |first2=T. Minh-Ha |date=2011 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0-415-58543-9 |location=Abingdon, Oxon [England]; New York |pages=39}}</ref> The Bimoda worship the deity Yennu<ref name=”pdf3″ /> and communicate with their ancestors using shrines.<ref name=”:32″ /> The Bimoda’s cultural practices of initiation<ref name=”:42″>{{Cite journal |last=Kreamer |first=Christine Mullen |date=1986 |title=THE ART AND RITUAL OF THE MOBA OF NORTHERN TOGO |url=https://www.proquest.com/docview/303480611?sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses |journal=Indiana University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses |pages=58–73}}</ref> and blood rituals are done to help strengthen their community and connection to their ancestors.<ref name=”:52″>{{Cite journal |last=Ateng |first=Mathias Awonnatey |last2=Nuhu |first2=Abukari |last3=Musah |first3=Agoswin A. |date=2022 |title=Blood ritual: An indigenous approach to peacemaking among the Bimoba people of northern Ghana |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/crq.21362 |journal=Conflict Resolution Quarterly |language=en |publication-date=2022 |volume=40 |issue=2 |page= |pages=231–247 |doi=10.1002/crq.21362 |issn=1536-5581 |via=Wiley Periodicals, Inc.}}</ref> The Bimoda sustain their living through their agriculture and livestock rearing.

The Moba held a clan-based society<ref name=”pdf3″>{{cite book |author1=J.J. Meij |url=https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/access/item%3A2923390/view |title=Testing Life history theory in a contemporary African population. Chapter 3 – The Bimoba: the people of Yennu |author2=D. van Bodegom |author3=D. Baya Laar |publisher=Thesis Leiden University, the Netherlands |year=2007}}</ref> that focus on their relationship with their ancestors.<ref name=”:32″>{{Cite book |last=Bourdier |first=Jean-Paul |title=Vernacular architecture of West Africa: a world in dwelling |last2=Trinh |first2=T. Minh-Ha |date=2011 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0-415-58543-9 |location=Abingdon, Oxon [England]; New York |pages=39}}</ref> The Bimoda worship the deity Yennu<ref name=”pdf3″ /> and communicate with their ancestors using shrines.<ref name=”:32″ /> The Bimoda’s cultural practices of initiation<ref name=”:42″>{{Cite journal |last=Kreamer |first=Christine Mullen |date=1986 |title=THE ART AND RITUAL OF THE MOBA OF NORTHERN TOGO |url=https://www.proquest.com/docview/303480611?sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses |journal=Indiana University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses |pages=58–73}}</ref> and blood rituals are done to help strengthen their community and connection to their ancestors.<ref name=”:52″>{{Cite journal |last=Ateng |first=Mathias Awonnatey |last2=Nuhu |first2=Abukari |last3=Musah |first3=Agoswin A. |date=2022 |title=Blood ritual: An indigenous approach to peacemaking among the Bimoba people of northern Ghana |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/crq.21362 |journal=Conflict Resolution Quarterly |language=en |publication-date=2022 |volume=40 |issue=2 |page= |pages=231–247 |doi=10.1002/crq.21362 |issn=1536-5581 |via=Wiley Periodicals, Inc.}}</ref> The Bimoda sustain their living through their agriculture and livestock rearing.

==Language==

==Language==

The Bimobas speak Moar (a Gur language, which is part of the larger Gurma language cluster. This language is an essential part of their cultural heritage and daily communication.

The Bimobas speak Moar (a Gur language, which is part of the larger Gurma language cluster. This language is an essential part of their cultural heritage and daily communication.

==Economy==

==Economy==

* [[Duut Emmanuel Kwame]]

* [[Duut Emmanuel Kwame]]

* [[Ghana]]

* [[Gur languages]]

* [[Joseph Yaani Labik]]

* [[Joseph Yaani Labik]]

* [[Moba language|Moba Language]]

* [[Moba language|Moba Language]]

* [[Tchitcherik]]

* [[Tchitcherik]]

* [[Togo]]

== References ==

== References ==

Ethnic group in Ghana and Togo

Ethnic group

The Moba, who go by Bimoba, also be known as Bimawba, B’Moba, or Moab, is an ethnic group that is primarily located in northern region in both Ghana and Togo. They speak a Niger-Congo language and is part of the Gurma cultural and linguistic group. There is an estimated 200,00 people that identify themselves as Bimoba[1] and about 481,500 people in northern Togo.[2] This group lives in the middle of the Dapaon territory. Who a lineage-focused paternal group perform with ceremonials that reflect their spiritual line.[3]

The Moba held a clan-based society[4] that focus on their relationship with their ancestors.[5] The Bimoda worship the deity Yennu[4] and communicate with their ancestors using shrines.[5] The Bimoda’s cultural practices of initiation[6] and blood rituals are done to help strengthen their community and connection to their ancestors.[7] The Bimoda sustain their living through their agriculture and livestock rearing.

The Bimoba are believed to have migrated southwards from present-day Burkina Faso following the collapse of the Kingdom of Fada-Gurma around 1420.[8] And the Bimoba may of have come with the Gourma migrations. However, it remains uncertain whether the Bimoba and the Gourma were originally the same people during these migrations.[9]

Bimoba society is patriarchal and is structured around clan and family heads. There are Clan-based kings or chiefs with vested power to hold the various clans together. The clans themselves can be located on multiple locations based on power and numbers. Presently, the clan groups of the Bimoba include Luok, Gnadaung, Dikperu, Puri, Tanmung, Gbong, Labsiak, Kunduek, Buok, the Baakpang, Turinwe, Nabakib, Naniik, Poukpera, Maab and Kanyakib.[8]

In Bimoba village, women usually reform the role of housekeeping and create useful objects. They create making pottery, wall decorating, and creating spaces inside there home.[10]

Tikpierroa are carvers in Bimoba society. Men learn woodcarving from within the family. Using adzes to make their work. Tikipierroa have wood that is maded into with little details, extended human features, and anthropomorphic style. These figures are called Tchitcheri figures.[11]

The Bimoba society has many types of marriages that can happen to be engaged:

- Puokpedu is the marriage off a women to a man. In addition, the groom’s family has to marry off a sister of his to bride’s family.[12]

- In Puokuul, if the groom is unable to provide a wife to the bride then he may have to work in farmland that her family owns.[12]

- Puopaab is when the head of the family agrees to marriage of their daughter (sometimes she is not born).[12]

- Puotugnu is nowadays an event where women can choose which man can abducted them for marriage.[12]

- Petulant Fallu happens if man dies while married. His wife are anticipated to marry into the recently dead’s family.[12]

- The Puoton/Taalon is a marriage where the groom’s lineage repays a needs to pay back to the bride, knowned as a ”woman-debt. This can make the bride feel force to stay with the groom.[12]

The Bimoba practice predominantly ethnic religions. They identify with personal deities collectively referred to as Yennu, which translates as “God”. Their ancestors play a role by being the contact between themselves and Yannu. A typical Bimoba compound would have a clay construction altar (patir; plural: pataa) in an enclosed hut (nakouk) where sacrifices are made to invoke the presence of the ancestors. Women are allowed into the nakuuk. Aside the patir located in the compound, every family member is allowed to construct their own small altar known as a mier. Communities may have a common shrine known as tingban. The tingban is visited at times of problems that concern the entire community such as a drought or a disease outbreak.[8]

The diviner in the Bimoda society is the one who asked to create shrine figures and to determine their reason, dimension, and identity. Doing this gives each tchitcheri a spiritual link between the living being and their descendants in both the real and spiritual world. There are many different kinds of Tchitcheri figures that are used in shrines.[13]

The Yendu tchitcheri are tiny shrine figures that relate to the Bimoba person’s connection to the God directly. These figures are constantly given gifts and drinks for warding away spirits and appeal.[13]

Bawoong tchitcheri

The household shrine is know as Bawoong. These figures can be found around Bimoba compounds. These shrines are put against exterior walls, lying on the ground, or placed near a sacrificial area that is marked by a circle of stones and pots. The bawoong shrine is believed to promote family health, and prosperity, ensure the fertility of livestock, and secure a harvest every year.[13]

The accompanying figures, bawoong tchitcheri, generally represent recent ancestors including parents and grandparents of the family. Their creation and placement are directed by diviners, who prescribe them to address family concerns such as infertility or animals who are suffering from disease. The diviner also identifies which ancestral spirit the figure represents, as this spirit serves as an intermediary between the family and God.[13]

tchitcherii sakab

Tchitcherii sakab are the shrine sculptures for the while village. These sculptures depict of the descendants of the Bimoba. They are oldest and biggest of the figures and are giving contributions that would help make sure that there would be growth and plentiful harvest.[13]

The Bimoba strength comes from ancestral authority, spiritual knowledge, and the wilderness, Kondi initiation rituals that symbolize transformation and social growth. The initiation uses the wilderness for this transformation. It translate the child from childhood to adulthood and becoming their own individual in the society.[6]

The male initiation happen in the woodland while the women initiation happens near the home. In both initiations the children get shaved heads and mark with a scar to symbolize their rebirth. This ritual follow strict rules that include dressing in special dress, having limits on their diet, and using a secret language. They also wear items of symbol ornaments that protect them with help from past familial and to be purity upon returning to the village.[6]

To rejoin society there is the Kondaak (“Kondi market”) ritual were individuals participating in the initiation stop by homes and getting gifts. During this ritual the participants wear metal jewelry, clothes that are red, and cowrie shells.[6]

Location and Settlement

[edit]

The Bimobas live in hilly and elevated areas, which historically provided strategic advantages for spotting potential threats. Their settlements are spread across the Northeasten Region of Ghana from Nakpanduri (Nanmanbour) to Bunkpurugu (Bunkperu) and the Dapaong region in Northern Togo. Nakpanduri historically means a place for eating meat while Bunkpurugu means an old river in Moar (local dialect). Towns and villages stretching from Nakpanduri to Bunkpururgu are inhabited by Bimobas.

While the Bimoba focus on both the bond between the living and their ancestors. They believed that these ancestors lived in the surrounding world and will continue to help and shield their tribe. Their alters are placed by the door of house and is to recognize to their ancestors. The land of the dead is found facing west of the Bimoba village as such the Bimoba houses can found facing west to help the spirits come back into the village.[5]

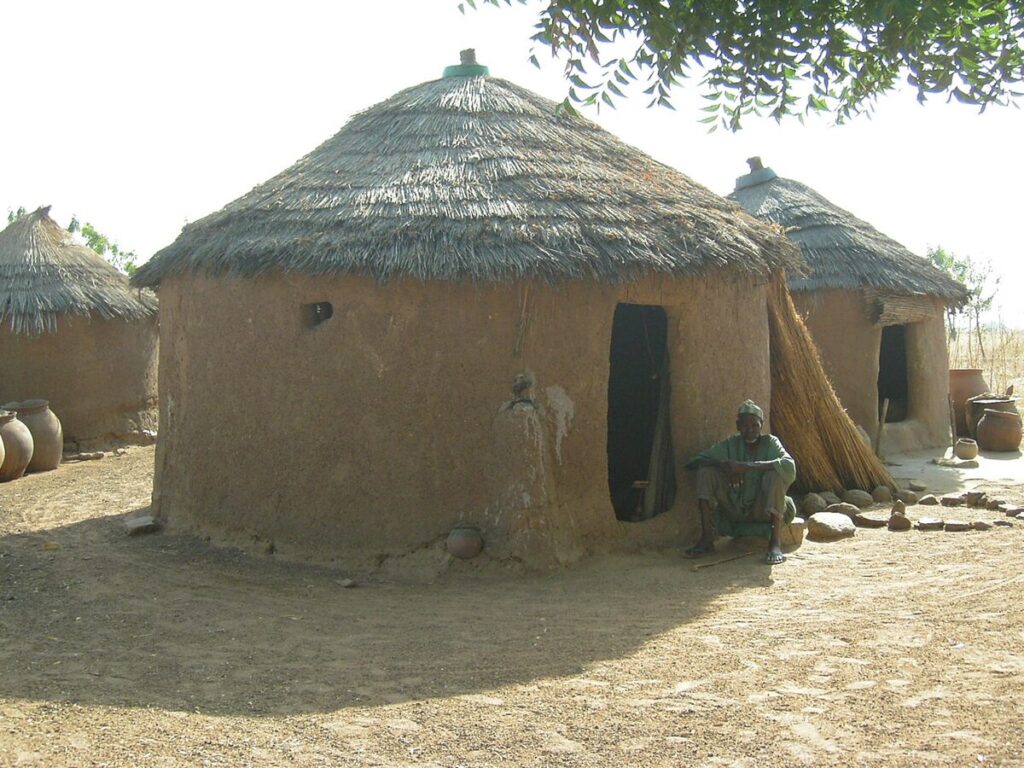

Their homes only grow or shrink depending on how many people are living in the household. For example, a baby being born will result in additional of a room being added into the home. It is also where society hast viewed this as having children is being a complete home.[14] Bimobas’ homes are circular walls made of mud and roof made from dry vegetation.[15] There are also distinct zones in the kitchen that are for having food store, preparing meals, and cooking.[10]

Bimobas have rich cultural traditions, including powerful initiation rites and spiritual practices. They are known for their mystical beliefs and reliance on traditional African spiritual charms. These practices are integral to their identity and survival as an ethnic group.’

There is a term Wari and it is used to talk about the details of a surface uses lines or engraved that can be seen on surfaces and usable objects.[16]

One of these ceremonies is an annual blood sacrifice. This event happen together with children and women. The ritual is to help resolve conflicts that can be over land, leadership, and relationships for both the present and the future. By doing this ritual help purifies the area to help conciliate the unliving while reforming bonds between the people. This ceremony helps strengthen the balance within the community and morality. The ceremonial is performed by having hole is made open where animal blood is gushed into it and then added with a weapon and symbolic objects. This is to symbolize as a seal for an agreement between foes, to removed bitterness of the past, and to make aggression into calmness. After the sacrifices are completed there is food for the community while vowing for continuous peace by taking on a hereditary pledge.[7]

Mostly women create pottery. The training of pottery usually happens with an expert relative. Those pots are made every day during drought and during growing season only occasional where only women will work on the pots. Women make these pots without a potter’s wheel and build them by hand using the convex mold method. Women pottery is more designs and colorful pots. Then Bimoba potters will fill the kiln. The older women potters usually watch the loading of the kilns and make harden of the pots. These pots are used for beer and to set for their income for their family[17]

The men make pottery by using the concave mold method making about the same pot and hardness in a day. Men make about twenty to thirty pots.[18] These male potters only make beer pots. The making of parts are only made for extra money and only made for only two months of the whole year.[19]

The Bimobas speak Moar (a Gur language, which is part of the larger Gurma language cluster. This language is an essential part of their cultural heritage and daily communication.

The Bimobas are primarily engaged in agriculture, growing crops such as millet, maize, groundnut, sorghum and yams. They also raise livestock, including cattle, goats, pigs, fowls and sheep.

- ^ Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis, eds. (2005). Africana: the encyclopedia of the African and African American experience. Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 426. ISBN 978-0-19-517055-9.

- ^ “Moba”.

- ^ Kreamer, Christine Mullen (1986). “THE ART AND RITUAL OF THE MOBA OF NORTHERN TOGO”. Indiana University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses: p, g, 52. ISBN 9798206289527.

- ^ a b J.J. Meij; D. van Bodegom; D. Baya Laar (2007). Testing Life history theory in a contemporary African population. Chapter 3 – The Bimoba: the people of Yennu. Thesis Leiden University, the Netherlands.

- ^ a b c Bourdier, Jean-Paul; Trinh, T. Minh-Ha (2011). Vernacular architecture of West Africa: a world in dwelling. Abingdon, Oxon [England]; New York: Routledge. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-415-58543-9.

- ^ a b c d Kreamer, Christine Mullen (1986). “THE ART AND RITUAL OF THE MOBA OF NORTHERN TOGO”. Indiana University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses: 58–73.

- ^ a b Ateng, Mathias Awonnatey; Nuhu, Abukari; Musah, Agoswin A. (2022). “Blood ritual: An indigenous approach to peacemaking among the Bimoba people of northern Ghana”. Conflict Resolution Quarterly. 40 (2): 231–247. doi:10.1002/crq.21362. ISSN 1536-5581 – via Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

- ^ a b c J.J. Meij; D. van Bodegom; D. Baya Laar (2007). Testing Life history theory in a contemporary African population. Chapter 3 – The Bimoba: the people of Yennu. Thesis Leiden University, the Netherlands.

- ^ Kreamer, Christine Mullen. “THE ART AND RITUAL OF THE MOBA OF NORTHERN TOGO”. Indiana University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses: 32.

- ^ a b Bourdier, Jean-Paul; Trinh, T. Minh-Ha (2011). Vernacular architecture of West Africa: a world in dwelling. Abingdon, Oxon [England]; New York: Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-415-58543-9.

- ^ Kreamer, Christine Mullen (1986). “THE ART AND RITUAL OF THE MOBA OF NORTHERN TOGO”. Indiana University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses: 52.

- ^ a b c d e f Pilon, Marc (1994). “Types of Marriage and Marital Stability: The Case of the Moba-Gurma of North Togo”. In Bledsoe, Caroline H.; Pison, Gilles; International Union for the Scientific Study of Population (eds.). Nuptiality in Sub-Saharan Africa: contemporary anthropological and demographic perspectives. International studies in demography. Oxford : New York: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press. pp. 132–134. ISBN 978-0-19-828761-2.

- ^ a b c d e Kreamer, Christine Mullen (1986). “THE ART AND RITUAL OF THE MOBA OF NORTHERN TOGO”. Indiana University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses: 52–54.

- ^ Bourdier, Jean-Paul; Trinh-Thi-Minh-Ha; Bourdier, Jean-Paul (2011). Vernacular architecture of West Africa: a world in dwelling. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-415-58543-9.

- ^ Kreamer, Christine Mullen (1986). “THE ART AND RITUAL OF THE MOBA OF NORTHERN TOGO”. Indiana University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses: 60.

- ^ Roy, Christopher D., ed. (2000). Clay and fire: pottery in Africa; [proceedings of a conference held at the Univ. of Iowa School of Art and History on April 8 – 9, 1994]. Iowa studies in African art. Iowa: School of Art and Art History, Univ. of Iowa. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-87414-120-7.

- ^ Kreamer, Christine Mulleen (2000). Roy, Christopher D. (ed.). Clay and fire: pottery in Africa; [proceedings of a conference held at the Univ. of Iowa School of Art and History on April 8 – 9, 1994]. Iowa studies in African art. Vol. IV. Iowa: School of Art and Art History, Univ. of Iowa. pp. 189–196. ISBN 978-0-87414-120-7.

- ^ Kreamer, Christine Mulleen (2000). Roy, Christopher D. (ed.). Clay and fire: pottery in Africa; [proceedings of a conference held at the Univ. of Iowa School of Art and History on April 8 – 9, 1994]. Iowa studies in African art. Vol. IV. Iowa: School of Art and Art History, Univ. of Iowa. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-87414-120-7.

- ^ Kreamer, Christine Mulleen (2000). Roy, Christopher D. (ed.). Clay and fire: pottery in Africa; [proceedings of a conference held at the Univ. of Iowa School of Art and History on April 8 – 9, 1994]. Iowa studies in African art. Vol. IV. Iowa: School of Art and Art History, Univ. of Iowa. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-87414-120-7.