{{

InterPro Family

}}

Protein family

| Nucleoplasmin family | |

|---|---|

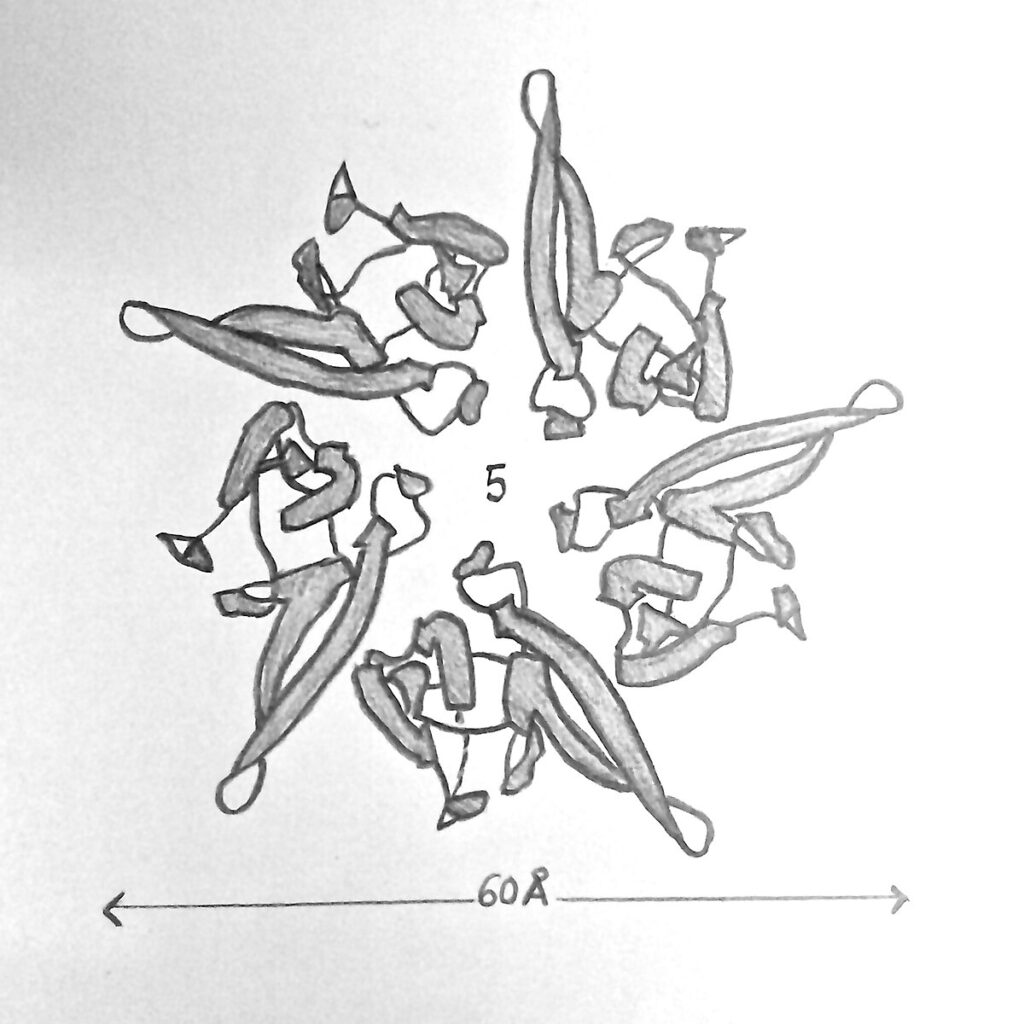

Fig 1. Illustration of the structure of nucleoplasmin |

|

| Symbol | NPM |

| InterPro | IPR004301 |

Nucleoplasmin (NPM2), the first identified molecular chaperone,[2] is a thermostable acidic protein with a pentameric structure. The protein was first isolated from Xenopus species,[3][4][5] and is now recognized as a highly conserved histone chaperone found across animals and other eukaryotes.[6][7]

The nucleoplasmin/nucleophosmin (NPM) protein family comprises Nucleophosmin (NPM1), Nucleoplasmin 2 (NPM2), Nucleoplasmin 3 (NPM3), and nucleoplasmin-like proteins (NLP).[8][9] These proteins typically share a pentameric N-terminal β-sandwich core.[7] While NPM1 functions broadly in nuclear organization and cellular homeostasis, NPM2 is primarily associated with histone chaperoning during early development and is most frequently described as the canonical nucleoplasmin.[8][10] The human NPM1 gene is also of clinical interest, as mutations in it are linked to acute myeloid leukemia (AML).[8]

In mammalian oocytes, NPM1, NPM2, and NPM3 are co-expressed and appear to function cooperatively during sperm chromatin remodeling, with NPM2 serving as the dominant oocyte form and NPM1 and NPM3 providing complementary and partially compensatory activities. This functional overlap is supported by evidence that the three proteins share similar histone chaperone properties and contribute collectively to paternal chromatin reorganization during early development.[11]

Human NPM paralogs also differ in their oligomerization behavior. NPM1 and NPM2 assemble into highly stable pentamers that can further associate into decamers, whereas NPM3 primarily forms dimers and becomes pentamer-competent only when incorporated into mixed complexes with NPM1. These hetero-oligomeric assemblies typically contain a 4:1 NPM1:NPM3 stoichiometry and have been demonstrated through crosslinking and blue-native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) analyses. Incorporation into such mixed pentamers enables NPM3 to acquire full histone chaperone activity, indicating a cooperative mechanism among NPM family members in vivo.[11] In addition, protein–protein interaction network analysis shows that NPM1, NPM2, and NPM3 each participate in distinct interaction clusters, with NPM2 most strongly associated with transcriptional regulation, chromatin structure organization, and cell cycle–related protein networks.[12]

Humans express three members of the nucleoplasmin family:

Protozoan Nucleoplasmin Homologs

[edit]

A nucleoplasmin-like histone chaperone has also been characterized in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum (PfNPM), whose N-terminal domain adopts the same β-sandwich fold seen in vertebrate nucleoplasmins and assembles into a stable pentamer. Phylogenetic analysis places PfNPM with FKBP-type and HD-tuin nucleoplasmin clades rather than with the vertebrate NPM1–3 group, indicating its divergent evolutionary origin.[7]

Structural studies of the P. falciparum nucleoplasmin homolog show that both the N- and C-termini extend from the distal face of the pentamer, reflecting an overall topology similar to NPM2 and other metazoan family members. Although this protozoan protein lacks the continuous A1 acidic tract found in vertebrate nucleoplasmins, it contains multiple acidic patches, including residues in loops L2 and L6, that generate a negatively charged surface suited for histone binding. Biophysical analyses further demonstrate that the P. falciparum pentamer is highly resistant to thermal and chemical denaturation, remaining intact at elevated temperatures and in high-salt environments, a property common across nucleoplasmins.[7]

Nucleoplasmin 2 (NPM2) is encoded by a gene on chromosome 8p21.3 and includes 10 exons producing a 214-amino-acid protein. [13] NPM2 has a two-domain architecture consisting of an N-terminal core domain (NTD) and a C-terminal tail domain.[14] The NTD forms a compact β-sandwich of eight antiparallel β-strands that assembles into a homopentamer, generating the characteristic doughnut-shaped oligomer of the nucleoplasmin family.[7][15] Crystal structures of the Xenopus nucleoplasmin core reveal that each monomer adopts a jellyroll-type β-barrel, and the resulting wedge-shaped subunits pack tightly to form a highly stable pentameric ring. The core domain also contains several conserved sequence motifs that stabilize the hydrophobic β-barrel and mediate contacts between neighboring pentamers, supporting higher-order oligomerization. Under certain conditions, two nucleoplasmin pentamers can associate into a decamer, providing an expanded platform for histone binding and storage.[16] Structural analyses indicate that specific residues—such as Glu57 in the conserved AKEE loop and Gln84 in the adjacent Q-loop—mediate inter-pentamer hydrogen bonding, contributing to decamer stabilization. Computational docking studies further support this interface, identifying Glu57 and Gln84 as key contact residues driving pentamer–pentamer recognition.[13]

The C-terminal tail is an intrinsically disordered region containing the acidic A1, A2 and A3 tracts, a bipartite nuclear localization signal, and KR-rich basic segment.[17] Unlike other nucleoplasmins, NPM2 contains a shortened A1 acidic loop consisting of a single glutamic acid residue (Glu37), which may contribute to the inability of its core domain to bind to histones directly. [13] The A2 acidic stretch serves as the principal histone-interaction and regulatory site.[17] Together, this pentameric and highly acidic structure provides a scaffold capable of simultaneously engaging multiple histones.[18] Structural analyses, including crystal and cryo-EM studies of nucleoplasmin-like proteins such as AtFKBP53, confirm that this overall fold and assembly mode are conserved across diverse eukaryotic species.[19]

NPM2 participates in various significant cellular activities like sperm chromatin remodeling, nucleosome assembly, genome stability, ribosome biogenesis, DNA replication, and transcriptional regulation.[5][20] During the assembly of regular nucleosomal arrays, these nucleoplasmins facilitate histone deposition onto DNA by binding to the histones and delivering them to nucleosomal templates. While some studies report that this reaction requires ATP,[3][21][22][23] others indicate that it can occur independently of ATP.[24][25] Their acidic regions mediate histone binding, allowing NPM2 to buffer, store, and release histones in a controlled manner while preventing nonspecific interaction during chromatin assembly.[14][9] As a result, NPM2 often participates in chromatin remodeling, contributing to gene expression, developmental processes, chromatin architecture, and the regulated deposition of histones.[14]

Maternal Histone Storage

[edit]

In Xenopus eggs, NPM2 functions as a storage histone chaperone, sequestering a large maternal pool of core histones that will later be used to package the rapidly replicating embryonic genome. Related nucleoplasmin family members in other species also act as sinks for histones displaced during sperm development and fertilization, ensuring balanced histone availability during early embryogenesis.[26]

Sperm Chromatin Remodeling

[edit]

This protein plays an essential role in remodeling sperm chromatin after fertilization. In vertebrates, it removes sperm-specific basic proteins and replaces them with histones, enabling the paternal DNA to decondense and become transcriptionally active.[27] Following fertilization, the paternal genome must undergo extensive reorganization before it can participate in embryonic development, and this process depends on the orderly exchange of sperm chromatin proteins for maternal histones.[28] The reconfiguration of paternal chromatin is an early developmental milestone that enables the formation of the functional male pronucleus and prepares the genome for the first round of DNA synthesis. Developmental studies across multiple species show that remodeling of sperm chromatin is a conserved requirement for initiating transcription from the paternal genome during early cleavage stages.[27] In this system, the transformation of sperm chromatin proceeds through stepwise displacement of sperm-specific nuclear proteins, establishing compatibility between the paternal and maternal pronuclei. These transitions occur before the first round of zygotic DNA replication and before the initiation of the early embryonic transcriptional program. Collectively, these events demonstrate the indispensable role of sperm chromatin remodeling in paternal genome activation and early embryogenesis.[28][11]

Beyond these in vivo functions, biochemical comparisons of human NPM paralogs have revealed additional mechanistic differences within the family. Chromatin remodeling and nucleosome assembly assays show that NPM1 and NPM2 each possess intrinsic nucleosome assembly activity, whereas NPM3 displays minimal activity on its own. NPM3 becomes functionally competent only when incorporated into hetero-oligomers with NPM1, indicating a cooperative mechanism among family members. Phosphorylation is also a key regulator of NPM2 activity: unmodified NPM2 exhibits lower sperm chromatin decondensation efficiency than NPM1, but phosphomimetic mutations at specific N-terminal and C-terminal residues markedly increase its sperm decondensation and histone-transfer activity, mirroring the activation that occurs during meiotic maturation in oocytes.[29][11]

Histone Interaction

[edit]

Histone association and release are regulated through a coordinated set of structural features within NPM2. The N-terminal core forms a pentameric β-sandwich that provides a stable scaffold for histone loading, while the intrinsically disordered C-terminal tail contains acidic stretches, including the A2 region, which structural analyses identify as the primary histone-binding interface.[6] A2 engages both H2A–H2B dimers and H3–H4 through a conserved acidic-aromatic motif. [11] Although NPM2 is highly acidic, structural analyses indicate that histone binding relies largely on hydrophobic interactions rather than electrostatic attraction. [12]

Experimental reconstitution assays further show that NPM2 associates with both H2A–H2B dimers and H3–H4 tetramers, supporting models in which nucleoplasmin stabilizes pre-assembled histone complexes prior to nucleosome deposition. [11] In addition to core histones, Xenopus NPM2 can also bind linker histones such as H1 and H5, exhibiting higher affinity for these variants and suggesting a dual role in histone storage and chromatin remodeling. Biochemical studies show that Xenopus NPM2 pentamers can bind up to five H2A–H2B dimers with decreasing affinity, supporting its role as a high-capacity histone storage chaperone.[12]

Computational docking studies predict three potential histone-binding pockets within the NPM2 core domain and suggest specific contacts with H2A–H2B dimers. Modeling and docking analyses indicate that NPM2 pentamers preferentially bind H2A–H2B dimers, whereas NPM2 decamers can accommodate both H2A–H2B dimers and H3–H4 tetramers, forming octamer-like complexes prior to nucleosome assembly. [13]

The tail also includes a basic C-terminal segment and a nuclear localization signal capable of folding back onto the A2, generating an autoinhibited state where key histone-binding residues are partially shielded. Histone binding disrupts these intramolecular contacts, shifting the tail into a more open conformation that exposes the acidic residues and promotes histone deposition. This regulatory “self-shielding” mechanism is considered a general feature of NPM2 and is likely conserved among other vertebrate nucleoplasmins.[6] Consistent with other histone chaperones, NPM2 is thought to prevent undesired histone–DNA and histone–histone interactions by transiently binding free histones and shielding their positively charged surfaces, thereby biasing assembly toward proper nucleosome formation rather than nonspecific aggregation.[26]

Post-translational Modifications

[edit]

NPM2 undergoes extensive post-translational modification during oocyte maturation and early embryogenesis. Documented modifications include phosphorylation, arginine methylation, and glutamylation.[30] These developmentally regulated modifications alter the structural openness of the C-terminal tail, modulate access to A2 acidic stretch, and directly influence the protein’s histone-binding affinity. [29] Phosphorylation enhances NPM2 activity primarily by inducing quaternary rearrangements of the pentamer rather than simply increasing negative charge. [12] By controlling the exposure of the primary histone-interaction site, these post-translational modifications fine-tune the balance between histone storage and release. Through these effects, post-translational changes in NPM2 contribute to its role in chromatin assembly and regulation during early development.[29] More broadly, NPM2 belongs to a class of histone chaperones that use acidic, often disordered regions to neutralize the positive charge of free histones, and post-translational modifications within these regions are thought to tune histone affinity and release in a context-dependent manner.[26]

Role in the Histone Chaperone Network

[edit]

Within the broader histone chaperone network, NPM2 cooperates with factors such as Nap1, Asf1, CAF-1, and HIRA, which collectively guide histones from cytoplasmic folding and nuclear import to deposition on DNA and subsequent exchange during replication and transcription. In this framework, NPM2 primarily contributes to histone storage and regulated release, rather than direct replication-coupled deposition like CAF-1 or HIRA.[26] During early embryogenesis, NPM2 also participates in a specialized chaperone system: together with the N1/N2 chaperones, which supply H3–H4 tetramers, and with Nap1, which deposits the embryonic linker histone B4, NPM2 helps assemble the paternal chromatin following fertilization until the mid-blastula transition. [31]

Clinical Significance

[edit]

Immunohistochemistry shows strong NPM2 staining in malignant peritoneal mesothelioma tissues, supporting a potential role for NPM2 in tumor pathology. NPM2 has also been implicated in tumor-associated chromatin regulation. Experimental studies suggest that NPM2 promotes histone deacetylation, contributing to transcriptional repression in pathological contexts. Elevated NPM2 expression is associated with poorer prognosis in malignant peritoneal mesothelioma, indicating a potential role in tumor progression and altered chromatin states. Analysis of TCGA datasets further shows that NPM2 expression differs significantly between tumor and normal tissues across numerous cancer types, including cholangiocarcinoma, colon adenocarcinoma, glioblastoma, renal carcinomas, and acute myeloid leukemia.[13]

- ^ a b “Search media – Wikimedia Commons”. commons.wikimedia.org. Retrieved 2025-12-01.

- ^ Dingwall C, Laskey RA (February 1990). “Nucleoplasmin: the archetypal molecular chaperone”. Seminars in Cell Biology. 1 (1): 11–17. PMID 1983266.

- ^ a b Rice P, Garduño R, Itoh T, Katagiri C, Ausio J (June 1995). “Nucleoplasmin-mediated decondensation of Mytilus sperm chromatin. Identification and partial characterization of a nucleoplasmin-like protein with sperm-nuclei decondensing activity in Mytilus californianus”. Biochemistry. 34 (23): 7563–7568. doi:10.1021/bi00023a001. PMID 7779801.

- ^ Dingwall C, Sharnick SV, Laskey RA (September 1982). “A polypeptide domain that specifies migration of nucleoplasmin into the nucleus”. Cell. 30 (2): 449–458. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(82)90242-2. PMID 6814762.

- ^ a b Tejun S, Yaozhou Z (2007). “Nucleoplasmin, an Important Nuclear Chaperone”. Chinese Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 23 (9): 718–723.

- ^ a b c Warren C, Matsui T, Karp JM, Onikubo T, Cahill S, Brenowitz M, et al. (December 2017). “Dynamic intramolecular regulation of the histone chaperone nucleoplasmin controls histone binding and release”. Nature Communications. 8 (1) 2215. Bibcode:2017NatCo…8.2215W. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02308-3. PMC 5738438. PMID 29263320.

- ^ a b c d e Saharan K, Baral S, Gandhi S, Singh AK, Ghosh S, Das R, et al. (April 2025). “Structure-function studies of a nucleoplasmin isoform from Plasmodium falciparum”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 301 (4) 108379. doi:10.1016/j.jbc.2025.108379. PMC 11993163. PMID 40049416.

- ^ a b c “InterPro”. www.ebi.ac.uk. Retrieved 2025-12-01.

- ^ a b Anselm E, Thomae AW, Jeyaprakash AA, Heun P (November 2018). “Oligomerization of Drosophila Nucleoplasmin-Like Protein is required for its centromere localization”. Nucleic Acids Research. 46 (21): 11274–11286. doi:10.1093/nar/gky988. PMC 6277087. PMID 30357352. Archived from the original on 2025-04-21.

- ^ “NPM1”, Wikipedia, 2025-11-02, retrieved 2025-12-01

- ^ a b c d e f Okuwaki M, Sumi A, Hisaoka M, Saotome-Nakamura A, Akashi S, Nishimura Y, et al. (June 2012). “Function of homo- and hetero-oligomers of human nucleoplasmin/nucleophosmin family proteins NPM1, NPM2 and NPM3 during sperm chromatin remodeling”. Nucleic Acids Research. 40 (11): 4861–4878. doi:10.1093/nar/gks162. PMC 3367197. PMID 22362753.

- ^ a b c d Finn RM, Ellard K, Eirín-López JM, Ausió J (2012). “Vertebrate nucleoplasmin and NASP: egg histone storage proteins with multiple chaperone activities”. The FASEB Journal. 26 (12): 4788–4804. doi:10.1096/fj.12-216663. ISSN 1530-6860.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e Wu Hl, Yang Zr, Yan Lj, Su Yd, Ma R, Li Y (2022-04-30). “NPM2 in malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: from basic tumor biology to clinical medicine”. World Journal of Surgical Oncology. 20 (1): 141. doi:10.1186/s12957-022-02604-3. ISSN 1477-7819. PMC 9055711. PMID 35490253.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c Franco A, Arranz R, Fernández-Rivero N, Velázquez-Campoy A, Martín-Benito J, Segura J, et al. (July 2019). “Structural insights into the ability of nucleoplasmin to assemble and chaperone histone octamers for DNA deposition”. Scientific Reports. 9 (1) 9487. Bibcode:2019NatSR…9.9487F. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-45726-7. PMC 6602930. PMID 31263230.

- ^ “Nucleoplasmin – Proteopedia, life in 3D”. proteopedia.org. Retrieved 2025-12-01.

- ^ Dutta S, Akey IV, Dingwall C, Hartman KL, Laue T, Nolte RT, et al. (October 2001). “The crystal structure of nucleoplasmin-core: implications for histone binding and nucleosome assembly”. Molecular Cell. 8 (4): 841–853. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00354-9. PMID 11684019.

- ^ a b Bañuelos S, Hierro A, Arizmendi JM, Montoya G, Prado A, Muga A (November 2003). “Activation mechanism of the nuclear chaperone nucleoplasmin: role of the core domain”. Journal of Molecular Biology. 334 (3): 585–593. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.067. PMID 14623196.

- ^ Platonova O, Akey IV, Head JF, Akey CW (September 2011). “Crystal structure and function of human nucleoplasmin (npm2): a histone chaperone in oocytes and embryos”. Biochemistry. 50 (37): 8078–8089. doi:10.1021/bi2006652. PMC 3172369. PMID 21863821.

- ^ Singh AK, Datta A, Jobichen C, Luan S, Vasudevan D (February 2020). “AtFKBP53: a chimeric histone chaperone with functional nucleoplasmin and PPIase domains”. Nucleic Acids Research. 48 (3): 1531–1550. doi:10.1093/nar/gkz1153. PMC 7026663. PMID 31807785.

- ^ Frehlick LJ, Eirín-López JM, Ausió J (January 2007). “New insights into the nucleophosmin/nucleoplasmin family of nuclear chaperones”. BioEssays. 29 (1): 49–59. doi:10.1002/bies.20512. PMID 17187372.

- ^ “Nucleoplasmin-like core domain superfamily”. Superfamily 1.75, HMM Library and Genome Assignment Server.

- ^ Ramos I, Fernández-Rivero N, Arranz R, Aloria K, Finn R, Arizmendi JM, et al. (January 2014). “The intrinsically disordered distal face of nucleoplasmin recognizes distinct oligomerization states of histones”. Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (2): 1311–1325. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt899. PMC 3902905. PMID 24121686.

- ^ “Nucleoplasmin family”. InterPro. EMBL-EBI, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus,European Molecular Biology Laboratory.

- ^ Warren C, Shechter D (August 2017). “Fly Fishing for Histones: Catch and Release by Histone Chaperone Intrinsically Disordered Regions and Acidic Stretches”. Journal of Molecular Biology. 429 (16): 2401–2426. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2017.06.005. PMC 5544577. PMID 28610839.

- ^ Elsässer SJ, D’Arcy S (2012-03-01). “Towards a mechanism for histone chaperones”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. Histone chaperones and Chromatin Assembly. 1819 (3–4): 211–221. doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.07.007. PMC 3315836. PMID 24459723.

- ^ a b c d Elsässer SJ, D’Arcy S (2013). “Towards a mechanism for histone chaperones”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. 1819 (3–4): 211–221. doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.07.007. PMC 3315836. PMID 24459723.

- ^ a b Imschenetzky M, Puchi M, Morín V, Medina R, Montecino M (December 2003). “Chromatin remodeling during sea urchin early development: molecular determinants for pronuclei formation and transcriptional activation”. Gene. 322: 33–46. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2003.08.024. PMID 14644495.

- ^ a b Lightsource SS (2018-02-28). “Structural Mechanisms of Histone Recognition by Histone Chaperones”. www-ssrl.slac.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2025-12-02.

- ^ a b c Leno GH, Mills AD, Philpott A, Laskey RA (March 1996). “Hyperphosphorylation of nucleoplasmin facilitates Xenopus sperm decondensation at fertilization”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 271 (13): 7253–7256. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.13.7253. PMID 8631735.

- ^ Onikubo T, Nicklay JJ, Xing L, Warren C, Anson B, Wang WL, et al. (March 2015). “Developmentally Regulated Post-translational Modification of Nucleoplasmin Controls Histone Sequestration and Deposition”. Cell Reports. 10 (10): 1735–1748. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.038. PMC 4567554. PMID 25772360.

- ^ Frehlick LJ, Eirín‐López José María, Ausió J (2007-01). “New insights into the nucleophosmin/nucleoplasmin family of nuclear chaperones”. BioEssays. 29 (1): 49–59. doi:10.1002/bies.20512. ISSN 0265-9247. ;

- Philpott A, Leno GH (May 1992). “Nucleoplasmin remodels sperm chromatin in Xenopus egg extracts”. Cell. 69 (5): 759–767. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90288-n. PMID 1591776.

- Laskey RA, Mills AD, Philpott A, Leno GH, Dilworth SM, Dingwall C (March 1993). “The role of nucleoplasmin in chromatin assembly and disassembly”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 339 (1289): 263–9, discussion 268–9. doi:10.1098/rstb.1993.0024. JSTOR 55822. PMID 8098530.