British stage, screen, radio actor

Peter Paul Wyngarde (23 or 28 August 1927 or 1928 – 15 January 2018), until 1945 called Cyril Louis Goldbert, was a British actor who spent his early life in the Far East. He had a successful career on stage from the mid-1940s and slowly gained screen roles, especially in television in the 1960s, before becoming well-known for portraying the character of Jason King in the television series Department S (1969) and Jason King (1971). His acting career came to an end in the 1990s, but he had occasional appearances in the 21st century.

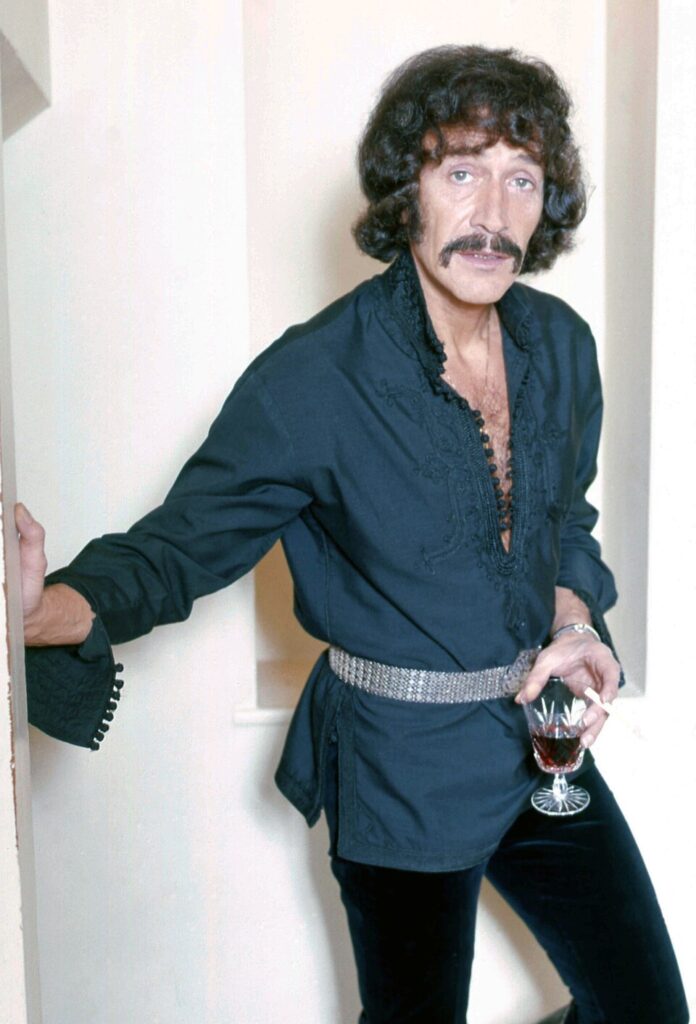

Wyngarde’s flamboyant dress sense and stylish performances led to his becoming a style icon in Britain and elsewhere in the early 1970s.[2][3]

Background and early life

Name

Wyngarde’s name as a child was Cyril Goldbert,[1][4] and in reporting his death BBC news gave his full name as Cyril Louis Goldbert,[5] which had been published in the Daily Mirror in 1996.[6]

Date of birth

By his own account, Wyngarde was born on 23 August 1933.[7][8] However, in an interview in 1993 he said he did not know his own age.[9] On 14 December 1945, he arrived in England on the SS Arawa, and the ship’s passenger list gives his age as 18, suggesting he was born before 15 December 1927.[10] On official documents related to sea voyages in 1960, to the United States and coming back, his date of birth was given as 28 August 1929.[11][12] In 2003, The Encyclopedia of British Film gave the year as 1927,[13] and the registration of his death states his date of birth as 23 August 1927.[14]

A biography published in 2020 which draws on personal knowledge of Wyngarde and on a large archive gives his date of birth as 28 (not 23) August 1928.[15] Most official documents state his year of birth as 1927 or 1929, while the more informal sources have reported a range of years between 1924 and 1937.[Note 1]

When appearing in a BBC television play in January 1950, Wyngarde was reported by a newspaper to be aged 25.[23]

After speaking to his mother in September 1956, The Straits Times said he was then aged 26.[24]

Wyngarde was first included on an electoral register in 1948, which might support 1927 as his year of birth, as only those aged 21 and over were allowed to vote in the United Kingdom at that time.[25][26]

Place of birth

Wyngarde’s mother seems to have told The Straits Times that he was born in Marseilles, France,[24] and Wyngarde said he was born at an aunt’s home in Marseilles.[7][8] His death registration states his birthplace as Singapore,[14] and for the sea voyages in 1960 his place of birth was also stated as Singapore.[11] In July 1972, he spent ninety minutes at Changi International Airport, Singapore, waiting for a connecting flight to Athens, and commented on this “I don’t believe I have been to Singapore”.[27] Throughout his life, Wyngarde gave Marseilles as his place of birth, and this is the view taken by the biography published in 2020.[15]

Family

When Peter Wyngarde travelled from Shanghai to Britain by sea in 1945, as Cyril Goldbert, the records of the ship, Arawa, name his next of kin as “Mr H. Goldbert, c/o Ministry of Shipping, London,[10] and the biography published in 2020 names him as Henry Goldbert.[15] Russian by birth, in October 1919 Goldbert was naturalized as a British subject in Singapore, with The Straits Times reporting that he had lived in the Straits Settlements for nineteen years.[28] Born in 1897, his parents were Marco Goldbert and Rosa Klivger,[29][30] and in April 1904 Mrs Goldbert took over the license of the Singapore Hotel[31][32] in North Bridge Road.[33]

In 1910, her licence was moved to another address.[34] In December 1906, Henry Goldbert won a school prize for “Scripture (Jews)”,[35] and in 1913 he was taking YMCA Engineering Classes and was about to sit for a Board of Education South Kensington certificate.[36]

Wyngarde’s mother was Marcheritta Marie Goldbert, born Ahin (1908–1992), known as Madge.[37] In interviews, Wyngarde said she was French.[38] There was a Eurasian family called Ahin living in Singapore.[39] She and Henry Goldbert were separated by 1937.[9]

On 6 March 1929, The Straits Echo reported that Mr H. Goldbert was leaving his position as branch manager of the United Motor Works, Seremban, and that he and his wife were about to leave for Singapore on the night mail train.[40]

In June 1934, in Singapore, a “V. Ahin”, described as a young Eurasian mechanic and a brother of Mrs Golbert (sic), was fined fifteen Straits dollars for his behaviour in March in trying to stop the posting of a summons on his sister’s door in Kim Yean Road.[41] A Victor Ahin was noted in 1941 as a nephew of Mr P. A. Ahin, chief engineer in the dredging section of the Public Works Department.[42]

Wyngarde had two younger Goldbert siblings: Adolphe Henry Peter Goldbert, also known as Joe (1930–2011), and Marion Colette Simone Goldbert (1932–2012). In 1946, they also came by ship from Shanghai to England, arriving at Southampton on RMS Strathmore on 30 April 1946, aged sixteen and thirteen, both stating their destination as Prenton, Birkenhead.[43] The 2020 biography of Wyngarde says he met them after their arrival but had little further contact with them or their children.[15]

Henry Goldbert had an older brother, Cyril Arthur Goldbert, born in 1895 in Mykolaiv, now in Ukraine, who died in 1958 in Australia.[44] A sea port of the Russian Empire, in the later 19th century about a fifth of Mykolaiv’s population was Jewish, and although the community suffered a pogrom in 1899, the same was true in 1926.[45] The surname Goldbert is rare, with only some 118 people worldwide known to be using it in 2025, almost half of them living in Israel.[46] If the Goldberts had been Jewish, conversions to Christianity were then common in the Russian Empire, with some 40,000 between 1836 and 1875,[47] and Wyngarde’s biographer reports that Henry Goldbert was a Roman Catholic.[15]

Henry Goldbert sailed on the RMS Britannic from Port Said to Liverpool in August 1944, giving his age as 47 and his occupation as Marine Engineer,[48] then some months later from Manchester to New York City, arriving there in May 1945.[49] Social security records in the United States give his date of birth as 1897 and his birthplace as “Hicolieff”, Soviet Union, and name his parents.[29] At the time of the 1950 United States census, Henry Goldbert was living in San Francisco, California, with his older sister Esther Reggoch, and was the owner of a barber shop. His age was given as 53, and he stated his marital status as “separated”.[50] Wyngarde visited San Francisco in July 1960.[11]

Wyngarde said that Henry Goldbert was one of his three stepfathers, and that his father was an Englishman named Henry Wyngarde[51][22]whose career in the British Diplomatic Service was in Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore, and India, before becoming an importer-exporter of antique watches living in Eaton Square, London.[52] No such person has been traced in public records.[53][29]

After Wyngarde’s parents divorced, the 2020 biography says his mother married Charles Juvet and had a son called Paul Edouard Juvet, born in 1938.[54][55] There was a Swiss horological family called Juvet based in Shanghai.[56][57] Such a stepfather may have inspired later claims that Wyngarde’s father was a dealer in antique watches and also that he was a maternal nephew of the French actor-director Louis Jouvet.[58] Evidence that his mother was a sister or sister-in-law of Louis Jouvet is lacking,[59] and Jouvet appears to be unrelated to the Swiss Juvet family. However, when Paul Edouard Juvet died at Geneva in 1998, Wyngarde is reported to have taken responsibility for settling his affairs and paying for his funeral.[54][55]

On 10 December 1947, at the Union Church in Shanghai, under the name of Marcheritta M. Goldbert, Wyngarde’s mother married John MacAulay, known as Ian, giving the name of her father as “Andrew Nicolich Ahin, deceased, [nationality] Swiss”.[60][53] After his mother’s marriage, Wyngarde sometimes used his new stepfather’s surname.[61]

The MacAulays lived in the Sultanate of Johor, Malaysia, until Ian MacAulay retired,[61] and in 1956 were living 140 miles from Singapore.[24] On their retirement to Britain, they settled in MacAulay’s home town of Stornoway, in Scotland.[61]

In 1952, Wyngarde’s brother was married at in the Church of England, at All Saints Church, Tudeley,[62] as Henry. A. P. Goldbert.[63] He was then serving in the Royal Navy and was described in a local newspaper as “second son of Mr and Mrs H. Goldbert of Kuala Lumpur Malaya”.[62]

Early life

Wyngarde’s mother told The Straits Times in 1956 that her son had spent “his first few years” in Malaya.[24]

Wyngarde often spoke about having had a traumatic early life.[9] In 2012, he wrote to his sister-in-law Lillian Goldbert “From early childhood we had to fend for ourselves.”[64] He told an interviewer that after his parents’ divorce, his father took him to China “only months before war with China broke out” in the summer of 1937.[9] He spoke about living in Shanghai when the Japanese Army took over the Shanghai International Settlement on 8 December 1941.[51] Correspondence between 1942 and 1943 held in the National Archives shows that in 1942 Henry Goldbert was serving on SS Lyemoon, that his three children, including 15-year-old Cyril, were then living in Shanghai, that efforts were being made by the British Ministry of War Transport, the Prisoners of War Department, and various boarding schools, to repatriate the children to Britain, and that Cyril could not be accommodated because of his age.[65]

Wyngarde was educated at the St Peter’s Boys’ School in Yuyuan Road, Shanghai, where after the arrival of the Japanese there were compulsory lessons in Japanese.[66] Yuyuan Road was within the Shanghai French Concession.[67]

In April 1943, Wyngarde was interned in the Lunghua civilian internment camp.[68] In one interview in the 1970s, he said he was interned as an unaccompanied five-year-old, due to an administrative error,[69] but this appears to be part of a scheme to lower his age, since the records show that he was interned from the age of fifteen to just before his 18th birthday. He began acting during his internment, when he played all the characters in a version of Doctor Jekyll and Mr Hyde.[70]

Interviewed by Ray Connolly in 1973, Wyngarde said: “As a child it was difficult to differentiate sometimes between fact and fantasy”.[71]

Following the Surrender of Japan, the internment camps were liberated in August 1945. Cyril Goldbert left Shanghai that autumn and travelled to England on the Cunard-White Star Line ship Arawa. Passenger records show that he travelled alone, aged eighteen, and arrived in Southampton on 14 December 1945.[10] He later said that the ship had arrived in Liverpool and that it was greeted by King George VI.[72][3]

The British author J. G. Ballard was also interned at the Lunghua camp and travelled to Britain in 1945 with Wyngarde and other former internees. In 1995, he wrote:

Peter Wyngarde was in the camp, under his real name of Cyril Goldbert. We came to England on the Arrawa, and I bumped into him once or twice in the 1950s. The last time, when he had begun to be successful, he cut me dead in St James’s Park. In interviews he claims that his father was a French [sic] diplomat and is vague about his age, sometimes claiming to be younger than me. In fact, he is at least four years older than me [Ballard was born in 1930], and played adult roles in the camp Shakespeare productions.[73]

Wyngarde always denied knowing Ballard or said he could not remember him, but in an undated letter published by his biographer in 2020 he said he had “pinned down” Ballard as a boy he had known in the camp who at the time was called Bryant.[64]

The Guardian newspaper said of Wyngarde in March 2020 that “his life story is shrouded in mystery”.[74] His own accounts of his life after leaving Shanghai for England appear to have been embellished with a history of medical treatment and education. This helped to account for the six-year gap created by his claim to have been a 12-year-old boy when he left Shanghai, rather than a man of eighteen. He said he had spent two years in a Swiss sanatorium, recovering from his war experiences. He was always vague about his education, but hinted that he had attended schools in Switzerland, France, and England,[75] after which he had studied law at Oxford and had worked in a London advertising agency for a while, before starting work as a professional actor.[51]

Career

Early stage career

Within a few months of his arrival in England in December 1945, Wyngarde began his professional acting career, adopting the new name of Peter Wyngarde. He first appeared on stage at the Buxton Playhouse in June 1946, playing Ensign Blades in Quality Street.[76][77] The theatre had just re-opened after being closed for six months.[78] Soon after that it presented J. B. Priestley‘s When We Are Married,[79] and in July of 1946 Wyngarde appeared in this at the Embassy Theatre, Hampstead, as Gerald Forbes. In the later months of 1946, he was on tour in a play called Pickup Girl, playing three parts.[77]

Towards the end of the following year, he had the role of Morris Dixon in a production of Noël Coward‘s Present Laughter at the Theatre Royal, Birmingham.[80]

In June 1949, Wyngarde was back at the Embassy Theatre, playing Cassio in a new production of Othello , with Michael Aldridge as Othello and Rosalind Boxall as Desdemona.[81]

In January 1950, the Essex Newsman reported that he was a former member of the Colchester Repertory company.[23] The same month, a new theatre company was formed at the Richmond Theatre, Richmond-upon-Thames, with Oliver Gordon as resident producer, the members including Martin Wyldeck, Raymond Francis, and Wyngarde.[82] In February, at Richmond, Wyngarde was in They Knew What They Wanted,[83] and in March in Mountain Air.[84]

In February 1951, as part of the Festival of Britain, Wyngarde appeared in Hamlet at the New Theatre, Bromley, playing Voltimand.[77]

In May 1952, he was back at the New Theatre, Bromley, appearing in a play called Separate Rooms, when on 6 May he was taken ill with an attack of malaria at Charing Cross Station while on his way to the theatre.[85] In June, he was at the Irving Theatre playing Jonah, the commander of an Israeli platoon surrounded by a minefield, in Natan Shaham’s They’ll Arrive To-morrow. This was the first Israeli play to be presented in London.[86] The reviewer of The Times said “Mr Peter Wyngarde, as the commanding officer, makes perhaps the strongest impression.”[87]

In April 1954, Wyngarde played the Ghost in an Arts Theatre production of The Enchanted by Giraudoux.[88] In June 1954, he was Fritz in Schnitzler’s Liebelei, opposite Jeanette Sterke.[89]

In September 1954 he was at the Arts Theatre playing Jean de Dunois in George Bernard Shaw‘s Saint Joan, with Siobhán McKenna and Kenneth Williams.[90]

On 24 April 1958, Wyngarde opened at the Apollo Theatre playing Count Marcellus in Duel of Angels with Vivien Leigh.[91] In the first half of 1959, he had a season at the Bristol Old Vic which he considered a highlight of his career.[51] He appeared as Petruchio in The Taming of the Shrew from 24 February to 14 March,[92] then

produced and directed the Eugene O’Neill play Long Day’s Journey into Night, which ran from 17 March to 7 April,[93] and finally from 19 May to 6 June 1959 played the title role in Cyrano de Bergerac.[92][77]

In the spring of 1960, a Duel of Angels production was put together for the United States, with a new cast, apart from Leigh and Wyngarde.[91] This opened at the Helen Hayes Theatre on Broadway and had a run there from 19 April to 1 June.[94] Wyngarde toured the US with the play and won both the San Francisco Award for Best Actor in a Foreign Play and a Tony Award for Most Promising Newcomer.[66] He returned to Britain in October.[95]

In 1968, Wyngarde had the part of Nikolay in The Duel, a play by John Holton Dell based on the novella by Chekhov, with Nyree Dawn Porter as Nadya. A tour of this production was launched at the Theatre Royal, Brighton, on 18 March.[96]

Early screen career

After making his film debut in an uncredited minor role as a soldier in Dick Barton Strikes Back (1949),[97] Wyngarde had more roles in television plays and series, and occasional films, in the 1950s.

His first credited screen role appears to have come in a BBC television play called “The Rope”, broadcast on 12 January 1950, playing Granillo, with David Markham.[23]

Soon after the launch of ITV, Wyngarde appeared on ITV Television Playhouse on 20 December 1956, in the play The Bridge by Joseph Schail, with Ingeborg Wells.[98]

He is said to have first become a “heart-throb” in 1957, in a BBC television adaptation of A Tale of Two Cities, playing Sydney Carton.[70] In August, he guest-starred in Overseas Press Club – Exclusive! in an episode about the killing of George Polk.[99]

In January 1958, he was in a production for television of The Dark is Light Enough, by Christopher Fry, with Dame Edith Evans in the part of Countess Ostenburg, which had been written for her.[100]

Beginning in May 1958, Wyngarde appeared as Long John Silver in a six-episode BBC serial of The Adventures of Ben Gunn, with Rupert Davies playing Captain Flint. The Kentish Independent found that “one of the smoothest, most sophisticated actors of to-day” had found a new angle on the part of Silver.[101]

In 1959, Wyngarde had a leading role in a dramatization of Julien Green‘s South, which may be the earliest television play with an openly homosexual theme.[102] In 1960, he was Roger Casement in the first episode of Granada Television‘s On Trial series, produced by Peter Wildeblood, and commented that “very little make-up was needed for the part… I am exactly Casement.”[103]

In April 1964, Wyngarde had the title role in Rupert of Hentzau on BBC1, with George Baker as Rudolf Rassendyll and Barbara Shelley as Queen Flavia.[104]

In a Play of the Week production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream for ITV, directed by Joan Kemp-Welch and broadcast on Midsummer’s Eve in June 1964, Wyngarde took the part of Oberon, king of the fairies, with Anna Massey as his Titania, Benny Hill as Bottom, and Alfie Bass as Fluke.[105]

Wyngarde’s film work was not extensive, but gained attention.[26] He took the role of Pausanias opposite Richard Burton in the film Alexander the Great (1956)[70] and with Donald Sinden had a major role in the film The Siege of Sidney Street (1960),[106] in which he “seethed anarchist fury”.[70] In Jack Clayton‘s The Innocents (1961), he had brief non-speaking scenes as the leering Peter Quint with Deborah Kerr and Pamela Franklin.[107] He followed this by starring in the occult thriller Night of the Eagle (1962), a rare film appearance in a lead role. The New York Times called the movie “quite the most effective ‘supernatural’ thriller since Village of the Damned“.[108]

In 1966, Wyngarde appeared in an episode of The Saint, “The Man who Liked Lions”, playing Tiberio, a assassin obsessed with lions. At the end, Tiberio and Simon Templar fight a duel in Roman costume, and Tiberio meets a sticky end, savaged by his own lion.[109]

Also in 1966, Wyngarde appeared with Diana Rigg and Patrick Macnee in The Avengers episode “A Touch of Brimstone“, as Cartney, leader of a recreation of the Hellfire Club.[70] In 1967, he returned as Stewart Kirby in another episode, “Epic”.[110]

He guest-starred in The Baron, The Troubleshooters, and I Spy.[70]

In 1967, he appeared in The Prisoner, in “Checkmate“, as the authority-figure called Number Two.[111]

In The Champions: “The Invisible Man” (1968), Wyngarde is a senior doctor gone to the bad, John Hallam, who has invented an “invisible man” device which can control people. He uses it to force Sir Frederick Howard (Basil Dignam) to steal gold bullion worth ten million pounds from the Bank of England for him.[112]

Wyngarde played himself as a Shakespearean actor in Lucy in London (1968), a television special starring Lucille Ball.[113]

Radio

Wyngarde played the journalist Nigel Bathgate on the BBC Light Programme, in a five-part dramatization of Ngaio Marsh‘s Artists in Crime, broadcast in August and September 1953, with Mavis Villiers as Bobbie O’Dawne.[114]

In August 1954, he starred with Dorothy Gordon in a BBC Radio production of Jean Anouilh‘s Léocadia, playing Prince Albert Troubiscoi, who is in love with an opera singer, Léocadia.[115] In April 1955, he again starred in an Anouilh play on BBC radio, this time voicing the part of Frantz in The Ermine.[116] He spoke the part of Orestes in the Oresteia of Aeschylus for the Third Programme, first broadcast in three parts on 27 May 1956, with Howard Marion-Crawford playing Agamemnon.[117]

In February 1957, again on the Third Programme, Wyngarde was the narrator for a BBC Drama Repertory Company performance of Anton Chekhov‘s Uncle Vanya.[118] In September, he had the title role of Sir Willoughby Patterne in BBC Radio’s dramatization of George Meredith‘s novel The Egoist.[119]

Wyngarde returned to radio in January 1967, in a broadcast of Terence Rattigan‘s The Sleeping Prince on the Home Service, with Millicent Martin and Fay Compton.

[120]

Jason King

Wyngarde became a British household name through his starring role in the spy-fi series Department S (1969–1970). His character, Jason King, a novelist and detective, was reputedly based on the author Ian Fleming.[70] Department S, a fictional division of Interpol based in Paris, dealt only with “inexplicable and baffling” cases and was masterminded by Sir Curtis Seretse, supported by a former CIA agent, Steward Sullivan, a computer expert, Annabelle Hurst, and King. Wyngarde persuaded the producers to model King on him, with the result that King led a hedonistic lifestyle in Paris, dressed decadently, and drove a Bentley S2 Continental sports saloon.[121] Wyngarde commented many years later “I decided Jason King was going to be an extension of me”. He noted that his hair was long at the time because he had just been appearing in a Chekhov play, The Duel,[9] and added in another interview that “Jason King had champagne and strawberries for breakfast, just as I did myself.”[7]

As early as 1964, Wyngarde was complaining that glamorous dressing gowns for men must have gone out of fashion, as they were so difficult for his wardrobe master to find.[122]

With its “peculiarly British humour”, Department S failed to sell to a United States network, which was then the touchstone for any ITC production, and only one series was made,[123]

but after the show ended, the character of Jason King was spun off into a new action series called Jason King (1971–1972).[121] The managing director of ITC, Lew Grade, told Wyngarde

“You, with your funny dark hair, moustache and terrible clothes, are not my idea of a hero at all, but my wife loves you, so you have to do another series.”[121]

One obituary described Wyngarde as playing the role “in the manner of a cat walking on tiptoe, with an air of self-satisfaction”.[124] The kinder assessment of Wyngarde’s Jason King in The Independent was that

He was frilly and flared in every way, like the Dr Who of the era, Jon Pertwee, another fully frilly and flared telly hero. He might as well have come from another planet, a sci-fi show such as Space: 1999 or The Tomorrow People… No TV personality rivalled Jason King for sheer insouciant, arch, camp style.[125]

The two television shows turned Wyngarde into an international celebrity, and he was mobbed by female fans on a visit to Australia.[9] Carl Gresham, his promotional manager at this time, said later that “During the ’70s we had a contract to officially open over 30 Woolworths newly refurbished stores throughout the UK. Other than my friends and clients, Morecambe & Wise, Peter was the most requested and highest paid celebrity making personal appearances.”[126]

In the role, The Herald reported that he “became a style icon, with his droopy moustache, hair that looked like a bearskin hat and a wardrobe of wide-lapelled, three-piece suits, cravats and open-necked shirts in colours so bright they might hurt sensitive eyes.”[2] In the summer of 1970, he won the John Stephen Fashion Award for Best Dressed Personality, given by Radio Luxembourg and decided by its listeners and by readers of Fab 208 magazine. Other nominees for the award included Cliff Richard and George Best, but they were far behind in the voting.[127] In 1971, there was a leap in the number of boys being called Jason, larger than for any other boy’s name.[128] At least one boy was given the names “Jason Wyngarde”.[129]

The Jason King show ran for one series of 26 fifty-minute episodes. More lightweight than Department S and more cheaply made, in Simon Heffer‘s assessment “Jason King saw Wyngarde become an ever-more comic turn.”[123] By 1972, Wyngarde had tired of playing this “blasé idiot”.[70]

Later career

In May 1972, Wyngarde was on stage at the Metro, Bourke Street, Melbourne, playing the title role in the first Australian production of Simon Gray‘s Butley. His performance got glowing reviews, and on 1 June The Stage reported that he had “scored a big hit”,[130] but nevertheless the play had a shorter run than was hoped.[131]

With Stanley Baker, Max Bygraves, Dickie Henderson, Cliff Michelmore, and Ron Moody, Wyngarde took part in a fund-raising lunch on 24 November 1972 to gather donations for children’s charities.[132]

On 5 January 1973, Wyngarde, Rolf Harris, and Katie Boyle were the judges in a television contest staged in Liverpool called “Miss TV Europe”, which was won by Sylvia Kristel. Wyngarde chaired the panel and presented the prizes.[133] From 22 January, he was back on stage, appearing for a week at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, in Mother Adam by Charles Dyer, playing Adam, a middle-aged museum attendant living with his crippled mother, played by Hermione Baddeley.[134]

At the end of January, this play went on tour, going next to the Playhouse, Weston-super-Mare,[135] and then in February on to Glasgow.[136] The Scotsman commented drily that “Peter Wyngarde has another try at breaking away from his image”.[137]

Wyngarde had said in 1972 that he had a “great wish to do a musical”.[138] On 21 June 1973, a front-page story in The Stage announced a major tour of a revival of the musical The King and I, with Wyngarde playing the King of Siam and Sally Ann Howes in the part of Anna. This show was launched at the Forum Theatre, Billingham, at the end of June[139] and went on to Birmingham, Glasgow, Hull, Leeds, Manchester, and Nottingham,[140] arriving at the Adelphi Theatre in the West End on 10 October 1973.[141] It ran until 25 May 1974, clocking up a total of 260 performances.[142]

In July 1974, at a trial at the Old Bailey, Jeremy Dallas-Cope, described as Wyngarde’s “£20-a-week male secretary”, was found guilty of forging nearly £3,000-worth of cheques from his employer’s bank account (equivalent to £38,832 in 2023) “to pay for his good life among the Chelsea elite”, and was sent to prison for two years. On being found out, Dallas-Cope had talked his flat-mate into attempting suicide and into taking the blame for the fraud. He too was convicted and given a prison sentence.[143]

Between January 1975 and the summer of that year, Wyngarde toured in the title role of Bram Stoker‘s Dracula, once again beginning at Billingham. The Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail noted that “COUNT DRACULA has risen from the grave once again to visit Billingham, but the intrepid Count will be a week late in arriving. The Count is making his bid for stardom on the stage of Billingham Forum Theatre later this month.”[144] Wyngarde later claimed that “My problem is that women fall in love with Jason King, but then find that I’m really Dracula”.[72]

Wyngarde’s career suffered a major setback from the publicity surrounding a conviction in October 1975 for “gross indecency” with a crane driver, and never fully recovered.[145][146][8] In 2008, the Irish Independent claimed the outcome was that “his career was terminated in 1975”.[147]

In July 1977, the Inland Revenue lodged a petition in the High Court of Justice for the winding-up of the company Wyngarde Productions,[148] and a winding-up order was made in October.[149] The liquidator took until May 1980 to finish his work,[150] and the company was dissolved in February 1984.[151]

In the late 1970s, Wyngarde worked in the theatre in South Africa and Austria.[72] In October 1978, he played an Arab oil sheikh for the film Himmel, Scheich und Wolkenbruch (“Sky, Sheikh and Cloudburst”), performing in German.[152]

Wyngarde took the role of the masked General Klytus in the film Flash Gordon (1980).[153] He later told an interviewer that at the height of his fame “I drank myself to a standstill … I am amazed I am still here”, but said he had stopped drinking in the early 1980s.[9]

On 22 November 1982, Wyngarde was declared bankrupt.[154] At the time, it was reported that his financial downfall had been caused by buying a farm in Gloucestershire for £53,000; within four years, his income had plummeted, and at the time of the hearing he was unemployed and living on social security.[155] He was discharged from bankruptcy on 14 June 1988.[156]

In 1983, at the Royal Alexandra Theatre, Toronto, and at the Prince of Wales Theatre in the West End, he appeared as Alexander Howard in the thriller Underground, with Raymond Burr and Marc Sinden.[157] In 1984, he was in The Two Ronnies Christmas Special, in “A Film Story”, as Sir Guy.[158]

In 1984, Wyngarde guest-starred in the Doctor Who four-episode story Planet of Fire. The TARDIS is on the planet Sarn, where Chief Elder Timanov (played by Wyngarde) is being troubled by the Master. Wyngarde decided to interpret Timonov as being much like Lawrence of Arabia, as played by Peter O’Toole in 1962.[159]

Also in 1984, with Carol Royle and Gareth Hunt Wyngarde had a leading role in the Hammer House of Mystery and Suspense story “And the Wall Came Tumbling Down“, in which action switches between the 1980s and the 1640s, with Wyngarde playing a member of a coven of witches and a general commanding a NATO nuclear base.[160]

In 1985, Wyngarde appeared on television in the first series of Bulman, playing Gallio, a vice boss, in the episode “I Met a Man Who Wasn’t There”. The Liverpool Echo interviewed him about the part, noting that it was “the latest in a string of baddies he has played to get away from the hero image”. It asked whether Jason King might yet return. Wyngarde said King had taken up four years of his life, and it was still possible the character could make a come-back.[161]

In August 1986, Wyngarde was at the Hilton British Airways Playhouse, at the Hilton Hotel, Singapore, playing a murderer, Roat, in Wait Until Dark. A local review found that he “comes across well as the diabolical Mr Roat, but his comic abilities hamper his transition into a seasoned and sadistic murderer.”[162] In 1989, in the film Tank Malling, he played Sir Robert Knight, a seriously wicked business man.[163]

In the 1990s, Wyngarde made appearances in The Lenny Henry Show (1994) and The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1994), playing the part of Langdale Pike in the episode “The Three Gables“.[164]

After leaving a stage production of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari in 1995, due to a throat infection, while the show was still in previews,[165] Wyngarde mostly stopped acting, apart from occasional voice work. He continued to appear in public at an event called “Memorabilia” and at others celebrating his past performances.[166][167]

In 1996, under the headline “Good buy for Jason: how are the mighty fallen”, the Daily Mirror printed a reader’s photo of Wyngarde looking at gentlemen’s overcoats in an Oxfam charity shop. Revisiting 1975, the story mocked “the discovery in court that the real name of this debonair heart-throb was Cyril Louis Goldbert”.[6]

21st century appearances

In October 2002, Wyngarde was one of the three subjects of an episode of the ITV programme After They Were Famous, together with Peter Sarstedt and Emlyn Hughes.[168][169] The programme revealed that since his days of stardom Wyngarde had taken up the sport of clay pigeon shooting.[170]

In March 2004, he took part for the fourth time in a charity clay pigeon shoot at Vera Lynn’s country estate at Ditchling, together with Vinnie Jones, Richard Dunwoody, and Ross Burden.[171]

Wyngarde and Cleo Rocos appeared on Channel 4 as guests of Simon Dee, in a one-episode revival of his chat show Dee Time, in January 2004.[172]

Screenwriter Mark Millar has said that when he was casting his film Layer Cake (2004), the director Matthew Vaughn wanted Wyngarde for a part in it, but was told he had died.[173] Seven years later, Vaughn again requested him, this time for a role in X-Men: First Class, but was again wrongly told that Wyngarde was dead.[173]

In 2007, Wyngarde recorded extras for a DVD box-set of The Prisoner, including a mock interview segment called “The Pink Prisoner”.[174]

In December 2013, Wyngarde narrated an episode of the BBC Four Timeshift series, “How to Be Sherlock Holmes: The Many Faces of a Master Detective”.[175]

Wyngarde appeared as himself in It was Alright in the 1960s (2015), a documentary series for Channel 4. Asked about wearing blackface to play a Turk in The Saint, he said he had been uneasy about it and had done it only in the hope that a theatre director might pick him to play Othello.[176]

Recordings

In 1970, Wyngarde recorded an album released by RCA Victor entitled simply Peter Wyngarde, featuring a single, “La Ronde De L’Amour”/”The Way I Cry Over You”.[177] The album is a collection of spoken-word musical arrangements produced by Vic Smith and Hubert Thomas Valverde. Wyngarde claimed that: “It sold out in next to no time… but RCA point-blankly refused to press any more. I was fuming, as I’d been given a three-album contract with the company, who promised to release one LP every 12 months. The excuse was that production was being moved… They told me that everything would have to go on the back burner, but I just believe that they got cold feet“.[178] A promo single of the track “Rape” (re-titled “Peter Wyngarde Commits Rape”) was also issued in 1970[179] with the B-side “The Way I Cry Over You” and the serial number PW1.

In 1998, the album was reissued on CD by RPM Records, re-titled When Sex Leers Its Inquisitive Head.[180] The album is now usually treated as a curiosity because of its unusual spoken-word style and the controversial subject matter of some of the tracks.[181][182]

Personal life

In 1949, Wyngarde met the actress Dorinda Stevens. An obituary in The Times says they later went on holiday to Sicily and were married while there.[72] In 1950, Wyngarde was living at 56, Strand-on-the-Green, Chiswick.[183] In 1953, both Dorinda Wyngarde and Peter Wyngarde are recorded as living at 9, Holland Park, Kensington.[184] It lasted for three years,[138] and by November 1955 Stevens was described in a TV Times profile as “a bachelor girl, sharing a mews flat near Portland Place, London, with Cassio, her wire-haired terrier”.[185] In 1957, while filming in Karen, Kenya, she married the Canadian cinematographer William Michael Boultbee (1933–2005).[186]

Interviewed for The Sydney Morning Herald in 1972, Wyngarde said his biggest regret was that he “married far too young”, adding: “It lasted three years and the last year was pretty hell. However, one just goes on learning from one’s mistakes doesn’t one?”[138]

From 1956 to 1957, Wyngarde shared a flat with Ruby Talbot in London, and the 2020 biography cites the electoral roll as evidence that this was a romantic relationship.[187] At 11, Oxford Mews, Paddington, the names on the 1956 and 1957 lists of electors are “Ruby J. Talbot” and “Peter P. Wyngarde”.[188][189] At no. 4 were Lawrence Dundas, Earl of Ronaldshay, and his wife Katherine.[189] In July 1957, Talbot married Reginald Stenning at Chanctonbury.[190]

In the late 1950s, Wyngarde was living in a cottage he had bought in Kent, next door to the actress Edith Evans.[66] In 1958, he also rented a flat at number 1, Earls Terrace, off Kensington High Street, London, and would keep it for the rest of his life. He shared that flat for some years with fellow actor Alan Bates; according to some sources, this was a romantic relationship.[102][72][191] It was sometimes assumed within the acting community that Wyngarde was gay,[145] and while it has been claimed he was the target of the nickname “Petunia Winegum”,[191][192] this may have originated in a comedy sketch rather than really having been used.[2]

In 1958, Wyngarde appeared with Vivien Leigh in a stage production of Duel of Angels at the Apollo Theatre, and in 1960 they both went to New York to take the same parts in the play when it was presented there.[91] He became her lover after she ended her affair with Peter Finch,[75] and in June 1960 the Singapore Free Press carried a photo of the two with the caption “Vivien with Peter Wyngard, her frequent companion these days”.[193] Wyngarde later called Leigh “the love of my life”.[72]

On 25 October 1960, travelling first class on the Cunard liner RMS Queen Elizabeth, Wyngarde arrived at Southampton from New York City, giving his marital status as single, his date of birth as 27 July 1929, his occupation as “Actor”, and his address as “Conifer Tree, Kilndown, Cranbrook“.[95]

Wyngarde’s personal life came under scrutiny in October 1975 when he was prosecuted under his real name, Cyril Goldbert, for gross indecency with a crane driver in public toilets in Gloucester bus station.[72][194] The allegation related to the evening of 8 September of that year, and Wyngarde pleaded guilty.[195] His solicitor said in his defence that he was not a homosexual and “did not go in there for this purpose”, but he admitted to masturbation and sought to mitigate this as an “aberration” brought on by excessive drinking. Wyngarde was convicted and fined £75.[196] In April 2023, the Peter Wyngarde web site published an email from the Home Office saying “Further to your application on behalf of the deceased, since the conduct constituting the offence was perceived sexual activity between persons of the same sex (unproven), and the conviction met the conditions for a disregard, then he is posthumously pardoned. This is retrospective.”[197][198]

In December 1996, Wyngarde told the Scotland on Sunday newspaper that his reputation as a lady-killer was “not completely undeserved”, and added “There’s no such thing as being gay or bisexual or heterosexual. It’s just how you feel at the time. It’s about relationships.”[199] After his death, Bob Stanley posted on Twitter “My favourite Peter Wyngarde line, to a friend of mine over dinner, “I’m 50% vegetarian, 100% bisexual””, but the source of this is unclear.[200] In 2025, Simon Heffer repeated it, without attribution.[123]

In old age, Wyngarde answered questions about what he liked best. He said his favourite book was Brideshead Revisited, his favourite film The Thief of Baghdad (the Alexander Korda one) his favourite poet W. H. Auden, his favourite television shows Inspector Montalbano, Seinfeld, and True Crime, his favourite colour was azure blue, his favourite drink paw paw juice, and his favourite animal the panther. The person he most admired was Luchino Visconti. The sports he most enjoyed were fencing, tennis, pistol target shooting, and clay pigeon shooting. When asked what had been the best moment in his acting career, he replied “When the director of the famous Old Vic asked me to do a season there.”[51]

Wyngarde was a close friend of the singer Morrissey. When asked in 2021 “What deceased personal friend do you miss the most?”, Morrissey’s answer was “Victoria Wood or Peter Wyngarde.”[201] In his Autobiography (2013), he wrote about visiting Wyngarde’s flat in Earls Terrace:

It’s an Edwardian warren of clerical ferocity – a tornado of books and papers and swelling pyramids of typescripts, half-finished, half-begun. His voice is still of great clarity and sound, his eyes unchanged since that period known as his prime. But he is no longer on stage or television. Film generally tells us that people of Peter’s age don’t actually exist, or, if they do, they are hopelessly infirm and in the way of the main storyline. He sits before me as one who knew his duty and did it, beyond all praise, alive in the cinema of the mind.[202]

Death and legacy

Wyngarde died on 15 January 2018.[203] His agent and manager said on Good Morning Scotland that he had been admitted to the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital in October 2017 and had had a long illness.[204] He told Associated Press that “His mind was razor sharp until the end. He entertained that whole hospital.”[205]

Two members of the Goldbert family were appointed as the administrators of the estate,[1] seemingly against Wyngarde’s wishes.[61][206] Tina Wyngarde-Hopkins’s biography of Wyngarde and the Hellfire Club web site detail some disputes between the author and Wyngarde’s administrators and next of kin over his estate and the location of his remains. It transpired that they had been cremated at the Golders Green Cemetery.[15][206]

An auction of 250 items from the actor’s estate took place on 26 March 2020 and included books, pictures, props used on stage, a snakeskin jacket and other clothes, photographs, jewellery, and Wyngarde’s childhood teddy-bear.[207] All items were sold, and the auction fetched over £35,000.[208] The trophy for Best Dressed Personality of 1970, a hallmarked silver figure of Beau Brummell, with a plaque reading “John Stephen Fashion Award – Peter Wyngarde – Best Dressed Personality – 1970”, reached the highest sale price, with a winning bid of £2,200.[207][74]

Mike Myers credited Wyngarde with inspiring the character of Austin Powers.[2]

Biographies and appreciation societies

In 2012, a career biography of Wyngarde by Roger Langley, the organiser of Six of One, the appreciation society of The Prisoner television series, was published by Escape Books.[209] A second edition of the book appeared in 2019.[210]

Peter Wyngarde had an active fan club from the mid-1950s to 1985.[211] An appreciation society called the Hellfire Club was founded in 1992, with the actor’s support,[212] with Diana Rigg and Joel Fabiani among the members.[211] At first, the members received a quarterly magazine by post, with Issue Number 1 dated January 1993, and Issue Number 28 dated Autumn 1999.[211] This went online in October 1999[213] and as of 2025 the web site is still regularly updated.[214]

In 2020, the organiser of the Hellfire Club published a biography of Wyngarde, drawing on personal knowledge of him and on hundreds of documents from an archive she had built up over some thirty years.[15] In 2018, three weeks after his death, she had changed her surname from Bate to Wyngarde-Hopkins.[215]

Films

Television

- BBC television play “The Rope”, 12 January 1950, as Granillo[23]

- ITV Television Playhouse: “The Bridge”, 20 December 1956[98]

- BBC adaptation of A Tale of Two Cities (1957) as Sydney Carton[217]

- Overseas Press Club – Exclusive!: “The George Polk Story”, 3 August 1957, as Andrea Bakolas[99]

- The Adventures of Ben Gunn (from the novel by R. F. Delderfield, 1958), as Long John Silver[218]

- South (1959) based on the play ‘Sud’ by Julien Green[102]

- Play of the Week – A Midsummer Night’s Dream (24 June 1964), as Oberon[105]

- Rupert of Hentzau (1964) as Rupert[219]

- Sherlock Holmes in “The Illustrious Client” (1965) as Baron Gruner[220]

- The Troubleshooters: “A Nice Girl – Is She For Sale?” (November 1965) as Sheik Mohammed bin Falik[70]

- The Saint (two episodes, 1966–67)[9]

- The Avengers: “A Touch of Brimstone” (1966) as Cartney[221][70]

- The Avengers: “Epic” (1967), as Stewart Kirby[110]

- The Prisoner : “Checkmate” (1967) as Number Two[111]

- The Champions: “The Invisible Man” (1968) as Dr John Hallam[112]

- Department S (1969–1970) as Jason King[70]

- Jason King (1971–1972) as Jason King[70]

- Doctor Who: “Planet of Fire” (1984), as Timanov[159]

- Bulman: “I Met a Man Who Wasn’t There” (1985), as Gallio[161]

- Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes in “The Three Gables” (as Langdale Pike, 1994)

Notes

- ^ J. G. Ballard writes in his autobiography Miracles of Life that Cyril Goldbert, “the future Peter Wyngarde … was four years older than me…”[16] As Ballard was born in November 1930, this would indicate, if Ballard were correct, that Cyril Goldbert was born before November 1926. Records kept in Shanghai in 1943 say that Cyril Goldbert had been born in 1928, but not where.[17][18] The web site of his appreciation society has different birth dates: in 2016, while Wyngarde was alive, it was 23 August 1933,[19] and this was the date used by BAFTA in the obituary at its 2018 awards.[20] After his death, the birth date was amended to 28 August 1937, and a photograph of a page of a Bailiwick of Jersey passport showing that date was published,[19][21] and then in April 2019 it was amended to 28 August 1928.[22]

References

- ^ a b c “Deceased Estates Wyngarde Peter Paul (otherwise Cyril Goldbert)”, The Gazette, 2 May 2019, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ a b c d “Obituary – Peter Wyngarde, flamboyant actor known for Jason King and Flash Gordon”, The Herald (Glasgow), 18 January 2018, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ a b https://www.mirror.co.uk/3am/celebrity-news/how-peter-wyngarde-went-japanese-11875967 “How Peter Wyngarde went from Japanese prison camp to 70s style icon”], Daily Mirror, 19 January 2018, archived at archive.ph, accessed 6 September 2025

- ^ “Wills & probate: Deceased Estates”, The London Gazette, Issue 62632, 3 May 2019, p. 8100, accessed 13 September 2025

- ^ “Peter Wyngarde: Cult TV star who inspired Austin Powers dies aged 90”, BBC News, 18 January 2018, accessed 7 September 2025

- ^ a b “Good buy for Jason: how are the mighty fallen”, Daily Mirror, Saturday 25 May 1996, p. 7

- ^ a b c Marco Giannangeli, “Jason King still reigns, just less of a woman’s man”, 29 March 2015, Express.co.uk , archived at archive.ph, accessed 7 September 2025

- ^ a b c “Peter Wyngarde”, National Portrait Gallery, London, accessed 7 September 2025

- ^ a b c d e f g h “From the archive: Andrew Billen talks to Peter Wyngarde in 1993”, The Observer Sunday 19 December 1993, accessed 9 September 2025

- ^ a b c “Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Inwards Passenger Lists, Class: BT26; Piece: 1215; Item: 46. SS Arawa, December 1945”, National Archives of the United Kingdom, Kew, England,,Ancestry.com, accessed 29 December 2017 (subscription required):

Name: C Gol[d]bert

Birth Date: abt 1927

Age: 18

Port of Departure: Shanghai, China

Arrival Date: 14 Dec 1945

Port of Arrival: Southampton, England

Ship Name: Arawa

Next of Kin: Mr H. Goldbert, c/o Ministry of Shipping, London

Shipping line: Cunard White Star

Official Number: 140148 - ^ a b c “California, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882–1959”, National Archives, Washington, D.C., at Ancestry.com, accessed 7 September 2017 (subscription required)

- ^ “UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960UK”, National Archives of the United Kingdom, at Ancestry.com, accessed 7 September 2017 (subscription required)

- ^ Anthony Slide, ed., The Encyclopedia of British Film (London: Methuen, 2003), p. 746

- ^ a b General Register Office for England and Wales, Reference: DOR Q1/2018 in KENSINGTON AND CHELSEA (239-1A), Entry Number 516736478

- ^ a b c d e f g Tina Wyngarde-Hopkins, Peter Wyngarde: A Life Amongst Strangers (London: Austin Macauley Publishers, 2020)

- ^ J. G. Ballard, Miracles of Life: Shanghai to Shepperton: an autobiography (London: Fourth Estate, 2008, ISBN 978-0-00-727072-9, see “Miracles of Life” full text online at archive.org, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ Document FO 916/1345, The National Archives, Kew, England

- ^ Adrian Room, Dictionary of Pseudonyms: 13,000 Assumed Names and Their Origins, 5th edition (McFarland, 2010, ISBN 9780786457632), page 516 at google.com

- ^ a b “Biography”, Hellfire Hall at wordpress.com, archived at archive.org 14 October 2016, and archived again 26 February 2018,accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ “Peter Wyngarde”, BAFTA web site (dead link)

- ^ “Wiki-Watch”, Hellfire Hall: Peter Wyngarde Appreciation Society, 15 December 2017, archived at archive.org 26 February 2018, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ a b “Biography”, Hellfire Hall: Peter Wyngard Appreciation Society, 19 April 2019 (dead link), archived 24 July 2019, accessed 13 September 2025

- ^ a b c d “IN TOWN TO-NIGHT”, Essex Newsman, Friday 13 January 1950, p. 2

- ^ a b c d “140-mile drive to see a very special film”, The Straits Times at gov.sg, 13 September 1956, p. 8, accessed 6 September 2025

- ^ London Electoral Roll, 1948, Camden, Hampstead area.

- ^ a b Brian McFarlane, ed., The Encyclopedia of British Film, fourth edition (Oxford University Press, 2016, ISBN 9781526111968, page=12 at Google Books (dead link)

- ^ “Sun-hunt lands Peter in S’pore”, New Nation newspaper (Singapore) at gov.sg newspaper archive, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ Untitled, The Straits Times, 25 October 1919, page 9, at gov.sg, accessed 6 September 2025

- ^ a b c US Social Security Applications and Claims Index, via ancestry.com. Name: Henry Goldbert

Gender: Male

Race: White

Birth Date: 1 Jan 1897

Birth Place: Hicolieff, Soviet Union

Father:

Marco Goldbert

Mother:

Rosa Klivger

SSN: 112227371

Notes: Oct 1945: Name listed as HENRY GOLDBERT Goldbert - ^ “U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936–2007”. Retrieved 23 July 2019 – via Ancestry.com.

- ^ “LICENSING JUSTICES”, The Straits Times, 8 April 1904, p. 5, at gov.sg, accessed 7 September 2025

- ^ “LICENSING JUSTICES”, The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), 13 October 1904, p. 236 at gov.sg, accessed 8 September 2025

- ^ “Public House Licences”, The Straits Times, 30 June 1904, p. 8, gov.sg, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ “LICENSING JUSTICES”, The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), 24 March 1910, p. 13 the new address was 46 & 47, Nelson Road, Singapore; online at gov.sg, accessed 8 September 2025

- ^ “The Prize List”, Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, 24 December 1906, p. 3 at gov.sg, accessed 8 September 2025

- ^ “Y.M.C.A. Engineering Classes”, The Straits Times, 7 February 1913, p. 10, gov.sg, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ Scottish Statutory Death Register 1992, ref. 221/ 96, Stornoway

- ^ Weekend magazine, 16 April 1969.

- ^ Myrna Braga-Blake, Ann Ebert-Oehlers, Alexius A. Pereira, Singapore Eurasians: Memories, Hopes and Dreams (World Scientific, 21 December 2016, ISBN 9789813109612), page 279

- ^ “Mr and Mrs H. Goldbert”, The Straits Echo (Mail Edition), Wednesday 6 March 1929, p. 191 at gov.sg, accessed 8 September 2025

- ^ “SERVICE OF A SUMMONS”, Malaya Tribune, 21 June 1934, p. 18, at gov.sg, accessed 9 September 2025

- ^ “Death of Eurasian Pensioner”, Malaya Tribune, 1 July 1941, p. 5, gov.sg, accessed 13 September 2025

- ^ “UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960”, Passenger list for RMS Strathmore, April 1946, ancestry.co.uk, accessed 10 September 2025 (subscription required):

Name: Marion Goldbert / Arrival Age: 13 / Birth Date: abt 1933 / Intended address: 28 Rocky Banks, Prenton, Birkenhead / Class: 1st / Profession Student; Name: Adolf Goldbert / Arrival Age: 16 / Birth Date: abt 1930 / Intended address: 28 Rocky Banks, Prenton, Birkenhead / Class: T.D. / Profession: Student;

Port of Departure: Shanghai, China / Arrival Date: 30 Apr 1946 / Port of Arrival: Southampton, England / Ports of Voyage: Shanghai and Hong Kong / Ship Name: Strathmore / Shipping Line: P. and O. Steam Navigation Company Ltd / Official Number: 164521 - ^ “Cyril Arthur Goldbert / Birth abt 1895, Mykolaiv, Ukraine / Death 23 Mar 1958, Turramurra, New South Wales, Australia / Mother Rosa Klivger / Father Marco Goldbert”, ancestry.com, accessed 7 September 2025 (subscription required)

- ^ “Mykolaiv, Ukraine”, Jewish Virtual Library, accessed 7 September 2025

- ^ “Goldbert Surname”, forebears.io, accessed 5 September 2025

- ^ Missionsblatt des Rheinisch-Westphälischen Vereins für Israel (Barmen: J. F. Steinhaus: 1878), p. 122 (in German)

- ^ “Henry Goldbert in the UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960”, RMS Brittanic: “Henry Goldbert / Age 47 / Departure Port Said, Egypt /Arrival 14 Aug 1944, Liverpool, England / Occupation Marine Engineer: Country of Last Permanent Residence Middle East / Proposed address Officers Pool, Liverpool”, ancestry.com, accessed 5 September 2025 (subscription required)

- ^ New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957: “Name Harry Goldbert / Arrival Date 2 May 1945 / Birth about 1897 / Age 48 / Gender Male / Ethnicity/Nationality Russian / Port of Departure Manchester, England / Port of Arrival New York, New York, USA / Ship Name Llandaff / Household Members — ”

- ^ “Henry Goldbert, Birth Russia, Residence 1950 San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA” in 1950 United States Federal Census, ancestry.com, accessed 5 September 2025 (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e “Everything You Wanted to Know about Peter Wyngarde”, Hellfire Hall: Peter Wyngarde Appreciation Society, 3 April 2017, archived 24 July 2019, accessed 3 April 2025

- ^ “Wiki-Freaks”. Hellfire Hall. Official Peter Wyngarde Appreciation Society. 15 December 2017. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017.

- ^ a b “UK, Foreign and Overseas Registers of British Subjects, 1628–1969”, Ancestry.com, accesssed 7 September 2025

- ^ a b Wyngarde-Hopkins, page 20

- ^ a b “Thoughts of Peter”, The Hellfire Club, 22 July 2020, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ “Auction 93, Lot 131”, uhren-muser.de Archives, accessed 8 September 2025

- ^ “Le nouveau directeur de l’Office de propagande des vins de Neuchâtel” (PDF). Feuille d’avis de Neuchâtel (in French). 7 February 1955. p. 12.

- ^ “Peter Wyngarde – Most Wanted TV Personality”. The Age. Melbourne, Australia. 19 February 1970 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ “Jouvet: biography”. www.geocities.ws.

- ^ The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; General Register Office: Foreign Registers and Returns; Class: RG 33; Piece: 31

- ^ a b c d “Legal Statement”, HELLFIRE HALL, 14 May 2020 (dead link)

- ^ a b “Mr Goldbert and Miss Rabbit”, Sevenoaks Chronicle and Kentish Advertiser, Friday 2 May 1952, p. 7: “The wedding took place at All Saints’ Church Tudeley on Saturday [26 April] of Mr Henry Goldbert second son of Mr and Mrs H. Goldbert of Kuala Lumpur Malaya and Miss Lilian Rabbit only daughter of Mrs Ellis of Five Oak Green and the late Mr Rabbit. The Bridegroom is on leave from the Royal Navy.”

- ^ “Henry A P Goldbert in the England & Wales, Civil Registration Marriage Index, 1916-2005”, at Ancestry.com, accessed 12 September 2025 (subscription required); Name Henry A P Goldbert / Date Apr 1952 / Registration District Tonbridge / Spouse

Lilian G Rabbitt / Volume 5b / Page 1609 - ^ a b “YOU’VE READ THE BOOK… Now read it in Peter’s own words”, The Hellfire Club, 2 May 2021, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ Arrangements for repatriation from Shanghai of the children of Henry Goldbert of S.S. ‘LYEMOON’, The National Archives, Reference MT 9/3722. Repatriations (Code 115), 1942–1943; accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ a b c “BIOGRAPHY: Personal Information”, peterwyngarde.uk, undated, accessed 7 September 2025

- ^ Yuyuan Road – Shanghai’s Hidden Hipster Haven, trip.com, accessed 9 September 2025

- ^ Civil Assembly Organization entry list, British Residents’ Association, Shanghai, June 1943.

- ^ My Weekly magazine, 10 May 1975

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m David Parkinson, “In memory of Peter Wyngarde, debonair star behind Jason King”, British Film Institute, 18 January 2018, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ Steve O’Brien, “The enigmatic and scandalous life of 1970s heartthrob Peter Wyngarde”, Yahoo News, 19 July 2024, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ a b c d e f g “Peter Wyngarde: Flamboyant actor renowned for his salacious exploits who became a household name in the 1970s when he played TV sleuth Jason King”, The Times, 18 January 2018, archived at archive.ph

- ^ “Letter from J. G. Ballard on “Mr Chips,” Peter Wyngarde, etc.”, 2 December 1994, in JGB News No. 24, jgballard.ca, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ a b Steven Morris, “Peter Wyngarde memorabilia snapped up at auction”, The Guardian, 18 January 2018, accessed 10,September 2025

- ^ a b “Peter Wyngarde, actor known as the flamboyant Jason King – obituary”, The Daily Telegraph, 18 January 2018 (subscription required); archived at archive.ph, accessed 6 September 2025

- ^ “BUXTON PLAYHOUSE THEATRE”, Manchester Evening News, Friday 21 June 1946, p. 2

- ^ a b c d “Theatre performances”, peterwyngarde.uk, accessed 7 September 2025

- ^ “THE BUXTON PLAYHOUSE”, Alderley & Wilmslow Advertiser, Friday 12 July 1946, p. 3: “After being closed since last November the Playhouse Theatre Buxton was recently re-opened by Envoy Productions Ltd”

- ^ “BUXTON PLAYHOUSE THEATRE: WHEN WE ARE MARRIED”, Manchester Evening News, Tuesday 9 July 1946, p. 2

- ^ “NOEL COWARD AT HIS BEST”, Gloucestershire Echo, Tuesday 14 October 1947, p. 3

- ^ “Chit Chat”, The Stage, Thursday 23 June 1949, p. 6

- ^ Richmond Herald, Saturday 21 January 1950, p. 9

- ^ “They Knew What They Wanted”, Richmond Herald, Saturday 11 February 1950, p. 9

- ^ “Mountain Air”, Richmond Herald, Saturday 4 March 1950, p. 9

- ^ “Mr. Peter Wyngarde”, Bromley & West Kent Mercury, Friday 9 May 1952, p. 9

- ^ “CHIT CHAT”, The Stage, Thursday 19 June 1952, p. 8; “THE IRVING”, The Stage, Thursday 3 July 1952, p. 9

- ^ The Times, Friday 27 June 1952

- ^ “THE ENCHANTED”, The Sketch, Wednesday 21 April 1954, p. 30

- ^ “Liebelei”, Evening News (London), Friday 11 June 1954, p. 5

- ^ “LONDON THEATRE”, The Stage, Thursday 23 September 1954, p. 10

- ^ a b c “Vivien Leigh: The Later Years – Theatre, 1950s & 1960s”, The Vivien Leigh Pages, Dycks.com (2003), archived at archive.today, accessed 7 September 2025

- ^ a b “The theatre in Bristol”, Bristol Evening Post, Thursday 7 January 1960, p. 14

- ^ “Long Day’s Journey into Night”, theatricalia.com, undated, accessed 12 September 2025

- ^ “Duel of Angels”, The Broadway League, Internet Broadway Database (2012) at Ibdb.com, accessed 7 September 2025

- ^ a b “Peter Wyngarde, Birth 27 Jul 1929 / Departure New York, New York, USA / Arrival 25 Oct 1960 Southampton, England” in UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960, ancestry.com, accessed 4 September 2025 (subscription required)

- ^ “Chekhov adapted”, The Stage, Thursday 21 March 1968, p. 11

- ^ a b “REVIEW: Dick Barton Strikes Back!”, The Hellfire Club, 22 May 2017, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ a b “TV PAGE: TeleBriefs”, The Stage, Thursday 13 December 1956, p. 12

- ^ a b “Overseas Press Club-Exclusive! (1957)” ctva.biz, accessed 13 September 2025

- ^ “The Dark is Light Enough”, Daily Mirror, Saturday 25 January 1958, p. 15

- ^ “A NEW ANGLE ON LONG JOHN SILVER”, Kentish Independent, Friday 30 May 1958, p. 8

- ^ a b c Mark Brown, “Newly unearthed ITV play could be first ever gay television drama”, The Guardian, 16 March 2013, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ “Peter Wyngarde as Roget Casement”, Nottingham Evening News, Friday 8 July 1960, p. 9

- ^ “Television Today: New Sunday serial for BBC 1”, The Stage, Thursday 16 April 1964, p. 9

- ^ a b “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (article), TV Times for 21–27 June, 1964, p. 10

- ^ a b “Watch and Download “The Siege of Sidney Street” courtesy of Jimbo Berkey”, free-classic-movies.com, accessed 19 January 2018

- ^ a b Andrew Pulver, “The Innocents: No 11 best horror film of all time”, The Guardian, 22 October 2010, accessed 19 January 2018

- ^ “Supernatural Thriller Is on Double Bill”, The New York Times, 5 July 1962, archived at archive.today 13 January 2025

- ^ “THE SAINT: The Man Who Liked Lions”, Daily Express, Saturday 26 November 1966, p. 12

- ^ a b “Epic: Steed Catches a Falling Star, Emma Makes a Movie”, theavengers.tv, accessed 13 September 2025

- ^ a b “The Prisoner: Checkmate”, Bristol Evening Post, Saturday 2 December 1967, p. 4

- ^ a b “The Champions – The Invisible Man”, Archive TV Musings”, 3 January 2020, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ “Screening TV”, The Philadelphia Inquirer, Vol. 275, Issue 117, 25 October 1966, p. 36, at Newspapers.com

- ^ “Light Programme, Drama, 1953”, Sutton Elms, undated, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ “Milk Pudding a la Mode”, Birmingham Daily Post, Thursday 5 August 1954, p. 12

- ^ “THIRD PROGRAMME: The Ermine (play) with Peter Wyngarde”, Wolverhampton Express and Star, Saturday 2 April 1955, p. 7

- ^ “Third Programme”, Kensington News and West London Times, Friday 25 May 1956, p. 5

- ^ Third Programme: Drama, 1957, Sutton Elms, undated, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ Portsmouth Evening News, Monday 2 September 1957, p. 4

- ^ “Saturday Night Theatre 1960-1970”, Sutton Elms, undated, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ a b c Andrew B. Roberts, “Peter Wyngarde as Jason King – the Bentley-driving international man of mystery”, The Daily Telegraph, 22 January 2018 (subscription required), archived at archive.ph, accessed 6 September 2025

- ^ “HAVE glamorous dressing gowns for men gone out of fashion?”, Nottingham Evening Post, Monday 10 August 1964, p. 7

- ^ a b c Simon Heffer, “Peter Wyngarde’s wayward life exposes the true cost of being a ‘cult actor’”, 18 May 2025 (subscription required), archived at archive.ph, accessed 7 September 2025

- ^ Gavin Gaughan, “Peter Wyngarde obituary”, The Guardian, 18 January 2018, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ Sean O’Grady, “Before Austin Powers there was ‘Jason King’ – and the fabulous Peter Wyngarde who has died aged 90”, The Independent, 18 January 2018, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ Vivien Mason, “Local radio presenter pays tribute to his friend and ’70s heart throb ‘Jason King'”, Bradford Telegraph and Argus, 19 January 2018, archived 22 July 2019

- ^

“Sense of occasion suits the Peter Wyngarde estate sale perfectly”, Antiques Trade Gazette, April 2020, accessed 7 September 2025 (subscription required) - ^ “Most popular baby names of 1971”, Momcozy.com, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ “Cowan, Jason Wyngarde”, General Register Office for England and Wales, Births March 1972, Doncaster, volume 2b, page no. 1952

- ^ “CHIT CHAT”, The Stage, Thursday 1 June 1972, p. 8

- ^ Frank Thring, Roland Roccheccioli, The Actor who Laughed (Hutchinson of Australia, 1985), p. 95

- ^ “Oh, Jenny you’re not wearing any”, Daily Express, Saturday 25 November 1972, p. 9

- ^ “Dutch girl is Miss TV Europe”, The Stage, Thursday 11 January 1973, p. 20: “Peter Wyngarde was chairman of the judges and presented the prizes.”

- ^ “HERMIONE BADDELEY, PETER WYNGARDE, in MOTHER ADAM by CHARLES DYER, Directed by the Author”, Birmingham Daily Post, 8 January 1973, p. 3

- ^ “Weston-super-Mare Playhouse: Look Ladies JASON KING is here!”, Bristol Evening Post, Tuesday 30 January 1973, p. 34

- ^ “MOTHER ADAM a battle between Youth and Age”, Daily Record (Lanarkshire, Scotland), Friday 9 February 1973, p. 25

- ^ “KING’S, GLASGOW”, The Scotsman, Tuesday 13 February 1973, p. 9

- ^ a b c Gary Shelley, Peter Wyngarde – An Incurable Romantic”, The Sydney Morning Herald, 8 May 1972, page 9, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ “MAJOR TOUR OF ‘THE KING AND I'”, The Stage, Thursday 21 June 1973, p. 1

- ^ Adrian Wright, West End Broadway (Woodridge: Boydell Press, 2012), p. 92

- ^ “ANNA AND KING COME BACK TO THE ADELPHI”, The Stage, Thursday 11 October 1973, p. 1: “Sally Ann Howes and Peter Wyngarde play Anna and the King of Siam…”

- ^ Stanley Green, Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre (Hachette Books, 1970, ISBN 978-0-7867-4684-2), p. 233

- ^ “Death Plan ‘bordered on evil'”, Newcastle Journal, 26 July 1974, p. 5, at British Newspaper Archive: “Peter Wyngarde’s £20-a-week male secretary helped himself to nearly £3,000 from the star’s bank account to pay for his good life among the Chelsea elite, an Old Bailey judge was told yesterday.” (registration required)

- ^ “COUNT DRACULA has been delayed”, Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail, Friday 3 January 1975 p. 4

- ^ a b Belam, Martin (18 January 2018). “‘What a life. What a legend’: tributes paid to cult TV star Peter Wyngarde – Television”. The Guardian. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ^ “A different era: how icon’s Gloucester Bus Station ‘liaison’ changed his world forever”, Gloucestershire Live, 23 January 2018, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ “Acting to Singing”, Irish Independent, Saturday 31 May 2008, p. 65

- ^ The London Gazette,

Issue 47292, 5 August 1977, p. 10225 - ^ The London Gazette, Issue 47360, 25 October 1977, p. 13496

- ^ The London Gazette, Issue 48202, 5 June 1980, p. 8176

- ^ The London Gazette, Issue 49653, 21 February 1984, p. 2510

- ^ a b “Himmel, Scheich und Wolkenbruch”, filmportal.de, undated, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ a b “From Jason King to Flash Gordon: Peter Wyngarde – a life in pictures”, The Guardian, 18 January 2018, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ “Wyngarde, Peter Paul” (PDF). The London Gazette. 8 November 1982. p. 16090.

- ^ “Former TV star bankrupt”, Belfast News-Letter, 25 November 1982, p. 1: “He disclosed that the purchase of a beautiful farm near S. Gloucestershire in 1973 had been his downfall. It had cost £53,000 — but within four years his income had plummeted. He was now unemployed and living on social security.”

- ^ “Wyngarde, Peter Paul” (PDF). The London Gazette. 1 September 1988. p. 9925.

- ^ British Theatre Guide, 1983.

- ^ “Christmas Special 1984, The Two Ronnies – BBC One”, bbc.co.uk, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ a b “Planet of Fire”, shannonsullivan.com, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ “Hammer House of Mystery and Suspense: And the Wall Came Tumbling Down”, peterwyngarde.uk, 28 November 2016, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ a b “COULD Jason King make a comeback? If Peter Wyngarde has his way he certainly could.” Liverpool Echo, Saturday 10 August 1985, p. 16

- ^ Jaime Lye, “Serving suspense at dinner”, The Business Times (Singapore), 30 August 1986, p. 6, gov.uk, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ a b CRUSADE: Jason gives up his hair to make a movie that matters”, Sunday Mirror, Sunday 11 September 1988, p. 37

- ^ Ian Smith, “REVIEW: The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes – ‘The Three Gables’”, peterwyngarde.uk, undated, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ “THE CABINET OF DR CALIGARI”, Peterwyngarde.wordpress.com, 2 July 2016, accessed 2 October 2016

- ^ David Bentley, “Which stars are appearing at MCM Birmingham Comic Con in 2016?”, 27 February 2016, Birmingham Mail, accessed 2 October 2016

- ^ “London Film Convention – Dates & Guests”, Showmasters Ltd, accessed 2 October 2016 (dead link), archived 23 September 2016 at archive.com

- ^ “After They Were Famous: Peter Wyngarde and Emlyn Hughes”, Irish Independent, Saturday 2 November 2002, p. 75

- ^ “AND CAN YOU GUESS WHO ELSE IS BACK ON THE BOX?”, Dundee Weekly News, Saturday 2 November 2002, p. 6: “ONE of the top icons of the Swinging 60s makes a rare TV appearance this Tuesday on After They Were Famous. Peter Wyngarde played the famous author/investigator Jason King in the hit series Department S. With his classic 60s looks and style, Peter Wyngarde…”

- ^ “After They Were Famous Updates on former celebrities”, Wolverhampton Express and Star, Saturday 2 November 2002, p. 33

- ^ “Charity clay pigeon shoot”, Sussex Express, Friday 5 March 2004, p. 23

- ^ “Dee’s tale is too much to live up to”, The Stage, Thursday 8 January 2004, p. 29

- ^ a b “Peter Wyngarde, star who played 1960s TV sleuth Jason King, dies”, Thejc.com, 18 January 2018, accessed 23 April 2020

- ^ “The Prisoner: The Pink Prisoner”, Thetvdb.com, undated, accessed 19 January 2018

- ^ “Web exclusive: Peter Wyngarde on double detection”, BBC, 23 December 2013, accessed 10 October 2015

- ^ “It Was Alright in the…”, Channel 4, accessed 2 October 2016

- ^ “Peter Wyngarde – la Ronde de l’Amour”. Discogs. 1970.

- ^ “When Sex Leers Its Inquisitive Head”. Peter Wyngarde Appreciation Society. 30 May 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ “Peter Wyngarde Discography”. Discogs.com. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ “Jason King – Shapers of the 80s”. shapersofthe80s.com. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ “Jason King’s Groovy Pad”, Optusnet.com.au, accessed 2 October 2016 (dead link)

- ^ “Peter Wyngarde: When Sex Leers Its Inquisitive Head” Dangerousminds.net, 20 March 2010, accessed 14 September 2025

- ^ Electoral Register for Brentford & Chiswick: Polling District N—Grove Park ward (1953), p. 8, Ancestry.com, accessed 13 September 2025 (subscription required)

- ^ Electoral Register for the Borough of Kensington and Chelsea: Polling District O—Holland ward (1953), p. 7 at ancestry.com, (subscription required)

- ^ “Dorinda Stevens R.I.P”, Filmdope.com, citing TV Times, November 1955 (dead link, as at 9 September 2025)

- ^ Janet Partridge, “Town Talk”, The Vancouver Sun, 20 April 1957, accessed 9 September 2025

- ^ “A Life Amongst Strangers’ Companion”, Peter Wyngarde Appreciation Society, 27 February 2020, accessed 13 September 2025

- ^ Borough of Paddington: South Division: Polling Dist. ZZ—Hyde Park Ward (part of) (1956), p. 16, Ancestry.com (subscription required)

- ^ a b Borough of Paddington: South Division: Polling Dist. ZZ—Hyde Park Ward (part of) (1957), p. 15, Ancestry.com (subscription required)

- ^ “Ruby J Talbot”

in the England & Wales, Civil Registration Marriage Index, 1916-2005, ancestry.com, accessed 6 September 2025 (subscription required) - ^ a b Lewis, Roger (28 June 2007). “The minute they got close, he ran”. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ^ “Peter Wyngarde: Jason King star who inspired Austin Powers dies aged 90”. Sky News. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ “Vivien revisits her old home to revive memories of happier days”, Singapore Free Press, 20 June 1960, p. 4, at gov.sh, accessed 9 September 2025

- ^ Peter Wyngarde: Cult TV star who inspired Austin Powers dies aged 90, BBC News, 18 January 2018

- ^ “DAILY RECORD Saturday October 18 1975”, Daily Record, Saturday 18 October 1975, p. 2

- ^ Kenneth Tew, “Peter Wyngarde fined £75 on bus station sex charge”, Evening Standard, 17 October 1975, p. 5, at Newspapers.com, accessed 9 September 2025

- ^ Tina Wyngarde-Hopkins, “CONTENTIOUS 1975 CONVICTION QUASHED!”, PETER WYNGARDE: The Official Website, April 2023, accessed 9 September 2025

- ^ “Disregards and pardons for historical gay sex convictions”. GOV.UK. 10 August 2023. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ^ Whatever happened to Peter Wyngarde, Scotland on Sunday, Sunday 8 December 1996, p. 46

- ^ Bob Stanley, Rocking Bob post, Jan 18, 2018, x.com, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ “Turning the Inside Out” Morrissey Central, 5 July 2021, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ “Peter Wyngarde has died”, Morrissey-solo.com, 18 January 2018, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ Actor Peter Wyngarde, star of Department S, dies aged 90″, The Guardian, 18 January 2018, archived 18 January 2018

- ^ “Peter Wyndgarde: The Man Behind the Moustache”, Good Morning Scotland – BBC Radio Scotland, 24 January 2018, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ “British Actor Peter Wyngarde Dies in London Hospital Aged 90”, The New York Times from Associated Press, 18 January 2018, archived at archive.org, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ a b “A Life Amongst Strangers’ Companion”, The Hellfire Club, 27 February 2020, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ a b “Peter Wyngarde – His Estate & Related Collections Auction on 26 March 2020 at 12:00 GMT, East Bristol Auctions, the-saleroom.com, accessed 23 April 2020

- ^ “Cult TV star Peter Wyngarde’s snakeskin jacket sells at auction”, BBC News, 27 March 2020, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ Roger Langley, Peter Wyngarde: King of TV (Ipswich, Suffolk: Escape Books, 2012)

- ^ “Peter Wyngarde Biography”, ESCAPE – Six of One The Prisoner Patrick McGoohan Portmeirion Web, undated, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ a b c “HISTORY OF THE OFFICIAL PETER WYNGARDE APPRECIATION SOCIETY”, peterwyngarde.uk, 13 May 2020, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ “THE HELLFIRE CLUB” (dead link), archived at archive.org, 14 September 2000, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ “PETER’S LOVE AFFAIR WITH HIS FANS”, Peterwyngarde.uk, 18 April 2017, accessed 10 September 2025

- ^ “PETER WYNGARDE The Official Website: Site Index”, undated, sccessed 10 September 2025

- ^ Gavin Llewellyn, Stoneking Solicitors, Changes of Name”, 8 February 2018, published in The Gazette, 10 July 2018, accessed 7 September 2025

- ^ “Night of the Eagle (Burn, Witch, Burn! )”, Rotten Tomatoes, 18 August 2015, accessed 13 September 2025

- ^ “A Tale of Two Cities 8 The Footsteps Die Out (1957)” (dead link), archived 20 January 2018 at archive.org, British Film Institute, accessed 11 September 2025

- ^ “REVIEW: The Adventures of Ben Gunn”, peterwyngarde.uk, 29 June 2016, accessed 19 January 2018

- ^ “TV Versions of ‘The Prisoner of Zenda’ & ‘Rupert of Hentzau'”, Silverwhistle.co.uk, accessed 19 January 2018

- ^ Alan Barnes, Sherlock Holmes on Screen, (Titan Books, 2011, ISBN 9780857687760), p. 190

- ^ “The Avengers Forever: Peter Wyngarde”, theavengers.tv, accessed 19 January 2018

External links

- Peter Wyngarde: The Official Website

- Peter Wyngarde at the British Film Institute

- Peter Wyngarde at IMDb

- Peter Wyngarde at the Internet Broadway Database

- Peter Wyngarde discography at Discogs

- Matthew Bannister, “The Last Word: Rick Jolly, Dolores O’Riordan, Cyrille Regis, Jenny Joseph, Peter Wyngarde” (BBC Radio 4, 21 January 2018)

- Andrew Stuttaford, “An International Man of Mystery”, National Review Online, February 17, 2018