Triggered by a recent social media ban, Nepal’s Gen Z took to the streets against corruption and nepotism. But none of them had foreseen the violence and unrest that transpired.

The week of September 8, 2025, was just another week for RC Gautam, an errand boy at Kantipur Television. During two decades of his employment at the station, he had seen several street protests, dire political situations, a civil war, shootouts, violence and even an attack on the channel’s headquarters. But September 9 panned out a bit differently for him.

“I can’t even begin to tell you how many people stormed our station. It all happened so quickly,” he told me over the phone.

An irate mob rushed into the Kantipur TV building on Tuesday, set fire to three buildings on its premises, torched two dozen bikes and over a dozen cars. The station was just one of the hundreds of buildings and homes that came under attack in the wake of what is being dubbed the ’Gen Z’ protests in Nepal, which quickly spiralled out of control on September 8.

Triggered by a recent social media ban, the demonstrators took to the streets against corruption and nepotism. Every day, about 2,000 Nepalis leave for the Gulf, Malaysia and other countries for work, and while the country runs on a remittance economy, the children of leaders and politicians lead lavish lifestyles — something the Gen Z have been criticising on social media.

When the protesters took to the streets on Monday, they had expected it to be peaceful. Initially, there was music and dancing as well, and some local celebrities showed up to support the movement. But things quickly spiralled out of control when some of the older men in the crowd targeted the parliament.

Thus began the rioting. Subsequently, the Kathmandu chief district officer issued orders to open fire, resulting in the deaths of 22 protesters. The numbers have since risen. Some of the protesters who died were in school uniforms. By September 10, a total of 30 people were reported dead. More than a thousand people injured in the protests are being treated in hospitals.

But the figures on casualties are being called conservative estimates. Many people remain missing and unaccounted for in similar events in different parts of the country.

The inferno

On September 9, violence escalated as groups of arsonists showed up on the streets, vandalising and torching private homes of ministers and businesses connected to those in power. Entire ministerial quarters, government buildings, police stations, the Supreme Court and the country’s main administrative block, Singha Durbar, were among those set on fire.

On Tuesday, Kathmandu burned and smelled of rage. The air was so thick, it was choking.

When smoke started filling the air in the Budanilkantha area, the north of the capital, where I live, and army choppers encircled the sky above me relentlessly, my instinct as a former reporter made me step out.

The Deuba residence, the home of former Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba and his wife, former minister Arju Deuba, had been attacked. A plume of smoke rose from their residence and lifted towards the Shivapur hill. Choppers made several rounds attempting to airlift the couple, who had been manhandled by the mob, but didn’t succeed. Gunshots were heard, and neighbours said two men had died — their deaths, not verified. The Deubas, injured, were eventually evacuated through the back door.

On the street across from where I live, smoke rose towards the sky — the air stank.

When I arrived at the scene, the arsonists had just left, and the public had open access to former President Bidhya Bhandari’s house, which was blazing. The crowd outside lingered and engaged in a tone of chit-chat. What I overheard:

“What did you take?”

“I didn’t really get my hands on anything.”

“There were 240,000 Nepalese rupees, and some USD. Some people took it.”

“Someone took a mattress.”

“I only took a cake.”

On my evening walks, going past the Bhandari home, I would often quickly scan the former president’s house, and the guards would be stationed at the security posts, armed. On Tuesday, as the house burned and the residents had been evacuated, the guards were still there outside the gate, waiting.

“This is our duty,” they said.

The scene at the Bhandari home was a common one across Kathmandu as arsonists ventured from neighbourhood to neighbourhood, torching and plundering the homes of ministers and administrators, beating them, stripping them.

Kathmandu was an inferno on September 9, as the fire brigades were forbidden to move by the police for security reasons. Even if they had been mobilised, they were never prepared for fire on such a great scale. No one had foreseen the violence and unrest of the nature that transpired.

The lull of sleeplessness

Most Nepalis have slept poorly since the killings on September 8. Most are seething or grieving. Or tired and scared. While the anger initially was directed at the KP Oli government and the ruling coalition for killing unarmed protesters, emotions had cascaded into confusion by the next day.

People no longer knew who was backing the arsonists or who seemed to be targeting specific homes and establishments as though they had been operating by a list, exercising what appeared like premeditated attack tactics.

Men on motorcycles were going door to door, causing arson and leaving behind a trail of what sounded like victory cries during battles. Some of them wielded guns they had stolen from police stations they had stormed. In Maharajgunj Chakrapath, the neighbourhood I grew up in, a high-ranking policeman was beaten to death by the mob. Some policemen were rescued and airlifted by army choppers on a sling.

This was the station my family and neighbours had looked to for security.

By the time the ‘Gen Z’, who were the ones to launch the protest in the first place, called for calm on social media and absolved themselves of responsibility for the riots, too much damage had been done. Their call had been for peaceful protests against corruption. But they no longer had control over the situation. Their movement had been hijacked.

When the Nepali army chief’s address was delivered on the evening of September 9, offering security — coupled with prohibitory orders — people sensed some form of respite in knowing that at least the rampage would stop if nothing more. Army trucks patrolled the city, but people still spent the night in fear. Unknown groups broke into private residences in some places; looting was reported in others. Prisoners had escaped en masse in different parts of the country.

As the mayhem unfolded, I was texting a young journalist friend who’s from outside Kathmandu and lives in the capital for work and studies. She said she felt scared. I told her I would probably sleep with a pair of scissors under my pillow, just in case. There were rumours that there had been stray incidents of men entering homes and raping women, something confirmed by the army later in an announcement.

Media during anarchy

During the attack on Kantipur TV on Tuesday, my former colleague, RC Gautam, was able to get away to safety. But with the army clampdown and curfew in place, he still hasn’t arrived home as I write this, and is instead sheltering with an acquaintance nearby.

“What will happen next, didi?” He asked me. “How am I going to feed the kids? How will I educate them? The office I worked at is gone.” I didn’t have an answer to give RC, but I mourned with him the loss of my former place of work, among many other things that have been lost to us within two days.

Kantipur TV, the biggest private legacy media, was known as an institution that stood its ground. And while media houses are also about their owners and their advertisers, they’re mostly about the journalists who run them. Especially the non-partisan ones, who give their lives to journalism so they can uphold high standards. Kantipur Media Group has had many journalists like that over the years, who’ve taken stands when the nation and the people needed it.

During the April 2006 street protests, hundreds of people had stopped outside the Kantipur complex in Tinkune to clap and show gratitude for the good journalism it had done. Those of us who worked there at the time looked outside the window, and some of us had tears of gratitude streaming down our faces.

The same establishment received a different kind of treatment. For many journalists who worked at Kantipur, their work was their home from where they launched treatises into the world, asked difficult questions and urged the Nepali people to think. The burning of Kantipur also points towards a troublesome point in Nepal’s history, where dedication to journalism has been vilified. Sure, some journalists take shortcuts, and all legacy media is funded by businesses, but they’re also run by journalists who believe in truth-telling. Free and fair journalism is the foundation of democracy, and pulling down a media house like Kantipur signals the close of a period that trusted independent media.

Questions abound

If one of the things this movement is demanding is the restoration of freedom of speech, then taking down a media house is a symbolic contradiction.

Which brings me back to the basics. Where does Nepal go from here? There’s no intel on this right now. Are there foreign elements at play? Vested interests of dormant political groups? Who instigated the riots? Who should lead next?

By the night of September 10, the Gen Z had spent an entire day discussing and closing in on who their choice of an interim leader could be. But discord and constitutional hurdles riddled their choices, as the nation listened in. Nepal is steeped in questions right now, and even though the answers are aplenty, none of them are right or wrong.

As of now, the country’s former chief justice, Sushila Karki, has claimed to have accepted the Gen Z protesters’ request to lead the interim government. “When they requested me, I accepted,” Karki told Indian news channel CNN-News18. “Gen Z” representatives told reporters that they met army officials later and proposed Karki as their choice to head an interim government.

International media and friends want to know what’s happening. Our DMs are flooded with messages of both care and mere curiosity, but the people are too tired right now. We’ve seen homes burn, we’ve watched loved ones die suddenly and quickly, our colleagues have been shot at, beaten up, and our friends and family robbed. We’ve also seen men brandishing guns and khukuris, threatening innocents.

Who are these men? Who is mobilising them? Where have the former ministers fled? Where are the ones who got away safely and went into hiding? Who is being sheltered at the army barracks? What is the army move likely to morph into? Who will the nation pick as its new leader? Will the president call for snap elections? Will the Constitution be amended? Who will comfort the mothers whose children died in the protests? What will happen to all the people who have lost their jobs because the buildings they worked in are now gone? Questions abound.

But for now, just in this moment, these queries must take a step back. Because right now, Nepalis need rest, support, and the strength to build back when all of this chaos ends and the air has cleared.

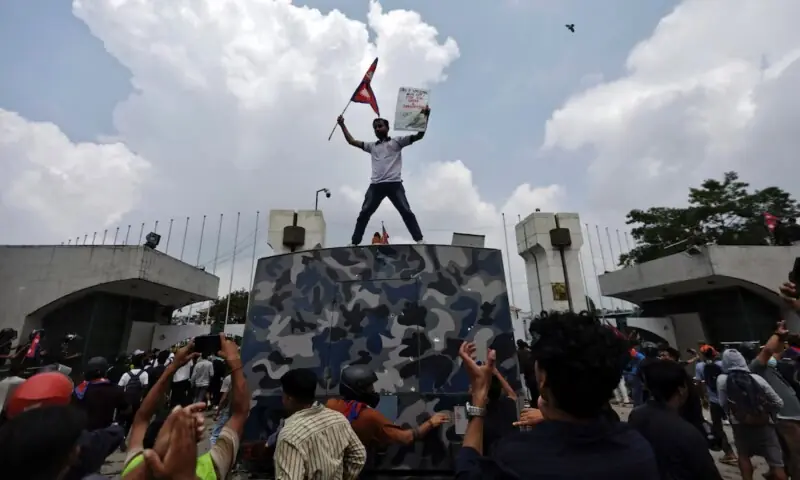

Header image: A demonstrator waves a flag as he stands atop a vehicle near the entrance of the Parliament during a protest against corruption and government’s decision to block several social media platforms, in Kathmandu, Nepal, September 8. — Reuters