Most of the first poem in [[Ezra Pound]]’s ”[[The Cantos]]” is a partial translation of the ”Odyssey”{{‘s}} 11th part. Pound’s translation was based on Andreas Divus’ faithful word-for-word Latin ”Odyssey”.{{Sfn|Cè|2020|pp=33–34}} Massimo Cè writes that that Divus’ faithful Latin translation has led some scholars to conclude that “we can treat both equally as source texts, with Divus acting as a window onto Homer”, but Cè argues that, while Pound’s language, meaning and metre is indebted to Divus’ version, they differ substantially from the Homeric Greek ”Odyssey”.{{Sfn|Cè|2020|p=35}} Pound’s translation mingled the conventions of Latin and Anglo-Saxon poetry.{{Sfn|Hardwick|2025|p=46}} In the 1940s, [[E. V. Rieu]] set out to make Homer accessible to new readers. [[Odyssey (E. V. Rieu)|Rieu’s ”Odyssey”]] was written in English prose and produced as the first entry in the mass-market paperback [[Penguin Classics]] series,{{Sfn|Bassnett|2025|pp=30–31}} for which he was the founding editor.{{Sfn|Cronin|2012|p=379}} Bassnett describes this release within the context of diminished interest in formal study of classical languages.{{Sfn|Bassnett|2025|pp=30–31}} Rieu’s translations were very successful; his prose approach inspired others in the post-war period.{{Sfn|Cronin|2012|p=379}}

Most of the first poem in [[Ezra Pound]]’s ”[[The Cantos]]” is a partial translation of the ”Odyssey”{{‘s}} 11th part. Pound’s translation was based on Andreas Divus’ faithful word-for-word Latin ”Odyssey”.{{Sfn|Cè|2020|pp=33–34}} Massimo Cè writes that that Divus’ faithful Latin translation has led some scholars to conclude that “we can treat both equally as source texts, with Divus acting as a window onto Homer”, but Cè argues that, while Pound’s language, meaning and metre is indebted to Divus’ version, they differ substantially from the Homeric Greek ”Odyssey”.{{Sfn|Cè|2020|p=35}} Pound’s translation mingled the conventions of Latin and Anglo-Saxon poetry.{{Sfn|Hardwick|2025|p=46}} In the 1940s, [[E. V. Rieu]] set out to make Homer accessible to new readers. [[Odyssey (E. V. Rieu)|Rieu’s ”Odyssey”]] was written in English prose and produced as the first entry in the mass-market paperback [[Penguin Classics]] series,{{Sfn|Bassnett|2025|pp=30–31}} for which he was the founding editor.{{Sfn|Cronin|2012|p=379}} Bassnett describes this release within the context of diminished interest in formal study of classical languages.{{Sfn|Bassnett|2025|pp=30–31}} Rieu’s translations were very successful; his prose approach inspired others in the post-war period.{{Sfn|Cronin|2012|p=379}}

In the twentieth century, several definitive translations appeared in languages that had already provided experiments in translation. Linguist {{ill|Luis Segalá y Estalella|es}} produced a new prose version in Spanish (1912), which remained highly popular, while a “careful” rendition into [[Catalan language|Catalan]] verse was completed by [[Carles Riba]] in 1919.{{sfn|García Gual|2015|p=131}} The first full version in Romanian, done by the [[Aromanians|Aromanian]] scholar [[George Murnu]], appeared in print in 1924,{{sfn|Tanașoca|1973|p=118}} the same year that [[Józef Wittlin]] completed his [[Polish language|Polish]] rendition (Wittlin revised his own work in several editions, down to 1957).{{sfn|Pomian|1976|p=9}} [[Ahmet Cevat Emre]] began working on a [[Turkish language|Turkish]] translation in the 1930s, at the behest of [[Mustafa Kemal Atatürk]]; the result was a two-volume edition, published in 1941–1942 by the [[Turkish Language Association]].{{sfn|Berk Albachten|2017|pp=295–297}} {{ill|Gábor Devecseri|hu|Devecseri Gábor}} published his Hungarian text in 1947.{{sfn|Horváth|1957|p=1424}} Later in the century, the ”Odyssey” was translated into some languages for the first time. A complete ”Odyssey” in [[Serbian language|Serbian]] was published in 1966 by [[Miloš N. Đurić]], and was immediately regarded as a major stylistic accomplishment.{{sfn|Gabela|1966}} {{ill|José Manuel Pabón|es}} gave a new Spanish translation in verse. Published in 1982, this translation was influenced by [[modernist poetry]], and by Riba, in its use of “accentual hexametres”.{{sfn|García Gual|2015|p=131}}

In the twentieth century, several definitive translations appeared in languages that had already provided experiments in translation. Linguist {{ill|Luis Segalá y Estalella|es}} produced a new prose version in Spanish (1912), which remained highly popular, while a “careful” rendition into [[Catalan language|Catalan]] verse was completed by [[Carles Riba]] in 1919.{{sfn|García Gual|2015|p=131}} The first full version in Romanian, done by the [[Aromanians|Aromanian]] scholar [[George Murnu]], appeared in print in 1924,{{sfn|Tanașoca|1973|p=118}} the same year that [[Józef Wittlin]] completed his [[Polish language|Polish]] rendition (Wittlin revised his own work in several editions, down to 1957).{{sfn|Pomian|1976|p=9}} [[Ahmet Cevat Emre]] began working on a [[Turkish language|Turkish]] translation in the 1930s, at the behest of [[Mustafa Kemal Atatürk]]; the result was a two-volume edition, published in 1941–1942 by the [[Turkish Language Association]].{{sfn|Berk Albachten|2017|pp=295–297}} {{ill|Gábor Devecseri|hu|Devecseri Gábor}} published his Hungarian text in 1947.{{sfn|Horváth|1957|p=1424}}

[[Luo Niansheng]] began translating the first [[Chinese language|Chinese-language]] ”Iliad” in the late 1980s, but he died before completing it; his student [[Wang Huansheng]] finished the project; [[Odyssey (Wang Huansheng translation)|Wang’s ”Odyssey”]] followed in 1997.{{Sfn|Zhang|2021|pp=353–354}} [[William Neill (poet)|William Neill]]’s translation of parts of the ”Odyssey” into [[Scots language]] (”Tales frae the Odyssey O Homer”),{{Sfn|Hardwick|2025|p=50}} published in 1991 by the [[Saltire Society]], was inspired by [[Gavin Douglas]]’ 16th-century translation. Hardwick uses Neill’s work as an example of a translation “enhancing the target language and culture”.{{Sfn|Hardwick|2025|pp=44–45}} [[Moshe Ha-Elion]]—a survivor of the [[Death marches during the Holocaust|death marches]] and [[Auschwitz concentration camp]]—translated [[The Odyssey (Moshe Ha-Elion translation)|the ”Odyssey”]] into [[Judaeo-Spanish]], a language with very few speakers. His hexameter composition was published in two parts from 2011 to 2014.{{Sfn|Armstrong|2025|p=2}}

[[Luo Niansheng]] began translating the first [[Chinese language|Chinese-language]] ”Iliad” in the late 1980s, but he died before completing it; his student [[Wang Huansheng]] finished the project; [[Odyssey (Wang Huansheng translation)|Wang’s ”Odyssey”]] followed in 1997.{{Sfn|Zhang|2021|pp=353–354}} [[William Neill (poet)|William Neill]]’s translation of parts of the ”Odyssey” into [[Scots language]] (”Tales frae the Odyssey O Homer”),{{Sfn|Hardwick|2025|p=50}} published in 1991 by the [[Saltire Society]], was inspired by [[Gavin Douglas]]’ 16th-century translation. Hardwick uses Neill’s work as an example of a translation “enhancing the target language and culture”.{{Sfn|Hardwick|2025|pp=44–45}} [[Moshe Ha-Elion]]—a survivor of the [[Death marches during the Holocaust|death marches]] and [[Auschwitz concentration camp]]—translated [[The Odyssey (Moshe Ha-Elion translation)|the ”Odyssey”]] into [[Judaeo-Spanish]], a language with very few speakers. His hexameter composition was published in two parts from 2011 to 2014.{{Sfn|Armstrong|2025|p=2}}

==See also==

==See also==

The Odyssey, an epic poem of ancient Greek literature attributed to Homer, has a long history of translation. The inaccessibility of Homeric Greek to most readers has driven continued interest in translations, which have played a crucial role in the epic’s cultural penetration through adaptation, selective reading, and linguistic transformation.

The earliest known translation of the text is Livius Andronicus‘s Latin Odusia (3rd century BCE)—it was one of the first Latin literary texts. Later notable translations include George Chapman‘s English versions in the early 17th century; Johann Heinrich Voss‘s influential 18th-century German translations that influenced development of the German language; Anne Dacier‘s French prose versions, published within the historical context of a French artistic debate; and Alexander Pope‘s 1720s English translation in heroic couplets. The 20th century saw innovations such as E. V. Rieu‘s accessible prose translation for Penguin Classics, and translations in minority languages, such as Moshe Ha-Elion‘s translation in Judaeo-Spanish or William Neill‘s in Scots.

Approaches to translation range from literal equivalence—attempts to replicate the formal meaning of the original text—to dynamic or communicative equivalence, which tries to translate the cultural context. The artificial literary nature of Homeric Greek presents some challenges for translators.

Translational approaches

[edit]

The language of the Homeric epics is inaccessible to the vast majority of readers, but interest in them, and related stories, remains quite strong. Susan Bassnett suggests that they owe their cultural penetration to adaptation, selective reading, and translation itself. Richard Armstrong argues that modern editions of the poems misled readers into believing there was a true “original” text—he says that in reality, translational reinterpretation is a central feature of the epic genre. Argentine essayist Jorge Luis Borges was a pioneer in analyzing the translations of the Odyssey: in a 1957 essay, he defined the whole corpus as an “international library”, noting its particular relevance to the development of English literature. Formal translation studies appeared as an academic discipline in the 1970s, but interest in translational scholarship increased substantially in the early twenty-first century. Earlier academic work relied on individual case studies, but systematic analysis in the twenty-first century have opened new interpretations and theoretical frameworks.

Armstrong summarises the traditional understanding of translational approaches:

- Literal translation (or “literal equivalence”) is the replacement of source words with equivalent language from the target. Translator aim to replicate the expression and formal meaning of the original text. There are challenges with this approach. Firstly, Homeric Greek was never used by real people—it was an artificial literary language (Kunstsprache). Some words also lose connotative meanings that are lost when translated literally.[a]

- Dynamic or communicative equivalence, or “sense-for-sense translation”, involves preserving the overall effect and purpose of the original text rather than finding direct analogues for words or maintaining sentence structure.

Spanish scholar Javier Franco Aixelá observed in 2012 that: “the Odyssey, or rhymed poetry in general, was translated mostly in rhymed verse in the past and mostly in prose or free verse today”, noting that this is due to “the conditions of reception of the society for which it is translated. […] translating the Odyssey into epic verse is not at all impossible, although it may be socially inconvenient in 21st-century Spain.”

Classical antiquity

[edit]

The Odyssey has a translation history stretching back to antiquity. The ancient conception of translation differs our modern perspective,[b] although the practices and customs were sometimes the same. In the period, the epics were named by their first lines—a practice that indicates their widespread fame. Livius Andronicus‘ Latin translation, Odusia, is one of the first Latin literary texts. He is widely regarded as the creator of the Latin literary tradition, and introduced a model of the epic to Roman society. He changed the metre of the Homeric Greek from dactylic hexameter to Saturnian, which may have been a calculation decision to foster interest in the epic among Roman readers. He may also have used his translation as a text in his own school.

Livius was translating a text of foreign origin, but it was easier for Romans to accept because it seemed Roman. Additionally, its genre was less likely to be embroiled in the Roman politics that a historical epic could cause. Not much is known about Odusia. The first line is faithful to the Homeric Greek, even matching its word order. He renders the adjective polytropon[c] as versutus (lit. ‘clever‘), and invokes the Camenae instead of the Muses. Surviving fragments have a different tone to the Homeric Greek; Livius’ also translocated some imagery from the Iliad into his Odyssey. Some evidence suggests that he condensed the twenty-four constituent parts into one, which would mean it was not a full translation.

Michael von Albrecht says Odusia was “beaten into” a young Horace (65–8 BC) as part of his education. Horace’s Ars Poetica (lit. ‘Art of Poetry‘) relates how to translate properly, describing it as the process of making communal material private. He thought poorly of literal translation. Horace translated the opening lines of the Odyssey twice, with very different outputs. In Ars Poetica, he summarises the plot in a single line; in Epistles he uses nine. His Ars Poetica translation omits polytropon entirely—McElduff describes this choice as Horace “correcting” Livius and demonstrating how to make a Greek text into a Roman one.

There is a hexametric Odyssea that is a distinct from Livius’s Odusia. Entitled Odusia Latina hexametris non multo post Ennium exarata in its modern edition, it survives only in four fragments. It may represent an epitomization or more likely a set of excerpts of the Odyssey, which, unlike the Iliad, frequently circulated as selections of excerpts. Edward Courtney, calling it Livius Refictus, considers it a reworking of Livius into hexameters under the influence of Ennius (fl. c. 200 BC). All the fragments are quotes from Priscian, citing Livius in Odyssea (or Odissia). Neither the original Odyssey nor Livius’s Odusia were divided into books, but the hexametric Oydssea was. The citations of Festus and Charisius to an Odyssia vetus (old Odyssey) are attempts to distinguish the original work of Livius from its hexametric competitor. The Homeric translations of Polybius and Attius Labeo have not survived. Labeo’s translations are known from the scholia of Persius (32–62 BC), who mocked him for his literal translations of both epics.[d]

Post-classical and Renaissance

[edit]

Beyond classical antiquity and into the Byzantine era, the spread of the Greek language—and the consequent internal translation of the Homeric texts as it spread—played a central role in maintaining the Odyssey‘s relevancy and esteemed status. Armstrong says both epics may have dropped from knowledge otherwise, using Beowulf as an example of this fate.

The Odyssey may have been translated into Syriac, but the evidence is inconclusive.

The 13th-century historian Barhebraeus records that Theophilus of Edessa (fl. c. 780) translated the “the two books of the poet Homer about the conquest of the city Ilion”, which seemingly refers to the Iliad and Odyssey, since only the Odyssey mentions the fall of Troy. Syriac quotations from Homer are found in the Rhetoric of Antony of Tagrit of 825 and one might be from the Odyssey. The Kingdom of Georgia, located on the margin of the Byzantine cultural realm, also had its own translations of both the Iliad and the Odyssey into its native language; these were completed in the eleventh or twelfth centuries by an anonymous author.

Nicholas Sigeros provided Petrarch with manuscripts of the Iliad and the Odyssey in 1354.[e] Petrarch’s correspondent Giovanni Boccaccio persuaded the monk Leonzio Pilato to produce translations in Latin prose—he finished the Iliad, but only came close to finishing the Odyssey. In or about 1462, Francesco Griffolini made a new paraphrastic prose translation into Latin for Pope Pius II. The first printed edition of the Odyssey in Greek was published in Milan 1488 by Demetrios Chalkokondyles, a Greek scholar resident in the Republic of Florence. Other noted editions appeared for the Latin version, beginning with that printed by Johann Schott of Strasbourg; new Latin versions or adaptations were put out by Andreas Divus and Raffaele Maffei. Divus’ translation was in a simplified version of Latin, and did not include with it the Homeric Greek text. A word-for-word rendition, it remained highly popular during those decades, although other writers had produced similar translations in the decades preceding Divus’ version.[f]

Printed translations for modern European languages surged in popularity in the sixteenth century; the inaugural book of this category was probably Simon Schaidenreisser‘s German print of 1537. Many of this group were only partial translations; parts eight through twelve of the poem (Odysseus’ account of his adventures) were the most commonly translated, which Jessica Wolfe says indicates that they were “read for recreation and not serious study”. Most of these were written in Latin. Renaissance readers particularly emphasised elements of colonial expansion and sea travel. In 1550, Gonzalo Pérez, a high-ranking bureaucrat of the Spanish Empire, published in Salamanca his draft of the poem, which in all ran at 21,944 verses; named Ulixea (rather than the updated Odisea), it is viewed as the first translation of that poem not just in Spanish, but in any Romance language. The first completed Italian Odyssey, written by Girolamo Baccelli in free verse, was published in 1582. The first completed French translation was composed in Alexandrine couplets by Salomon Certon and printed in 1604. It lost public favour following the Académie Française‘s language reforms in the 1630s and 1640s.[53]

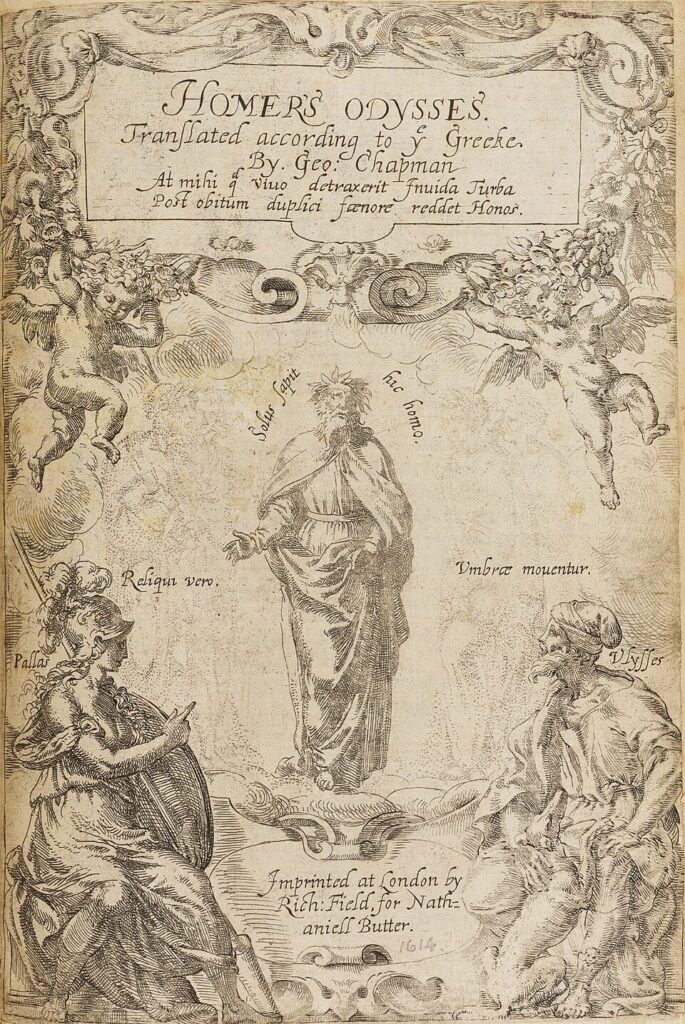

Arthur Hall was the first to translate Homer into English: his translation of the Iliad‘s first 10 books, which was published in 1581, relied upon a French version. George Chapman became the first writer to complete a translation of both epics into English after finishing his translation of the Odyssey. These translations were published together in 1616, but were serialised earlier, and became the first modern translations to enjoy widespread success. He worked on Homeric translation for most of his life, and his work later inspired John Keats‘ sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” (1816).

Johann Heinrich Voss‘ eighteenth-century translations of the epics are among his most celebrated works,[g] and profoundly influenced the German language. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe called Voss’ translations transformational masterpieces that initiated German interest in Hellenism. Anne Dacier composed her Iliad and Odyssey in French prose,[h] appearing in 1711 and 1716, respectively;[53] it was the standard French Homeric translation until the late eighteenth century.[64] Antoine Houdar de la Motte, who could not read Ancient Greek, used Dacier’s Iliad to produce his own contracted version, criticising Homer in the preface. His argument that he had improved upon Homer angered Dacier, who penned a 600-page rebuttal.[66]

Dacier’s translation of the Odyssey profoundly influenced the 1720s translation by Alexander Pope, which he produced for financial reasons years after his Iliad. Dacier did not speak English and used a poor translation to read Pope’s translation; she condemned it in a prefatory note a new version of her Iliad. Pope, an admirer of Dacier, was hurt; she died in 1720 before he could respond.[64] Pope translated twelve books himself and divided the other twelve between Elijah Fenton and William Broome; the latter also provided annotations. They were composed in heroic couplets—paired rhyming lines of iambic pentameter. This information eventually leaked, harming his reputation and profits. Armstrong describes a “battle of English poetic forms” following Pope’s translation: William Cowper translated rendered the epics in blank verse, the non-rhyming schema used by John Milton for Paradise Lost. Armstrong describes this battle continuing into the nineteenth century.

Pérez’s Spanish translation was the only such version of the poem until 1837, when Mariano Esparza of Mexico published his own—followed fifty years later by more professional version, the work of Spanish classicist Federico Baraibar. The first Portuguese-language Odyssey was translated by the journalist and politician Manuel Odorico Mendes (1799–1864), who also produced the first Portuguese versions of the Iliad, the Aeneid, and Virgil’s entire poetic corpus. Odorico combined the approaches of preceding Portuguese poets. The metre used was the decasyllable—an analogue to iambic pentameter―also employed by the sixteenth-century poet Luís de Camões in Os Lusíadas. One controversial feature was the use of composite words, borrowed from Ippolito Pindemonte, for the translation of epithets and other adjectives. According to Leonardo Antunes, the metre, together with the use of composite words, “created a translation that was harder to read than the actual Greek and Latin texts”.

Still in the eighteenth century, Bernardo Zamagna of Ragusa produced a widely circulated neo-Latin rendition of the Homeric poem. The early nineteenth century brought Homeric studies to other areas of East-Central and Eastern Europe. Possibly the first attempt to complete a Romanian version was that of Ioan Barac in Austrian Transylvania (a manuscript dated to 1816); Alecu Beldiman of Moldavia completed an all-prose translation at some point before 1837 (his remained a manuscript version, as was the fragmentary version done in 1852 by Wallachia‘s Alexandru Odobescu). The first Odyssey in the Russian language may have been Vasily Zhukovsky‘s 1849 translation in hexameter. Around that time, the first rendition into Hungarian was penned by István Szabó, followed by a succession of other translators—including Emil Ponori Thewrewk and János Csengery. Awareness of the Odyssey also spread about the Ottoman Empire, but no Ottoman Turkish translation was published—largely because the local intellectuals knew enough French to read it in French translations; by contrast, the Iliad had one such a rendition, presented in 1886 by Naim Frashëri.

Most of the first poem in Ezra Pound‘s The Cantos is a partial translation of the Odyssey‘s 11th part. Pound’s translation was based on Andreas Divus’ faithful word-for-word Latin Odyssey. Massimo Cè writes that that Divus’ faithful Latin translation has led some scholars to conclude that “we can treat both equally as source texts, with Divus acting as a window onto Homer”, but Cè argues that, while Pound’s language, meaning and metre is indebted to Divus’ version, they differ substantially from the Homeric Greek Odyssey. Pound’s translation mingled the conventions of Latin and Anglo-Saxon poetry. In the 1940s, E. V. Rieu set out to make Homer accessible to new readers. Rieu’s Odyssey was written in English prose and produced as the first entry in the mass-market paperback Penguin Classics series, for which he was the founding editor. Bassnett describes this release within the context of diminished interest in formal study of classical languages. Rieu’s translations were very successful; his prose approach inspired others in the post-war period.

In the twentieth century, several definitive translations appeared in languages that had already provided experiments in translation. Linguist Luis Segalá y Estalella produced a new prose version in Spanish (1912), which remained highly popular, while a “careful” rendition into Catalan verse was completed by Carles Riba in 1919. The first full version in Romanian, done by the Aromanian scholar George Murnu, appeared in print in 1924, the same year that Józef Wittlin completed his Polish rendition (Wittlin revised his own work in several editions, down to 1957). Ahmet Cevat Emre began working on a Turkish translation in the 1930s, at the behest of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk; the result was a two-volume edition, published in 1941–1942 by the Turkish Language Association. Gábor Devecseri published his Hungarian text in 1947.

Later in the century, the Odyssey was translated into some languages for the first time. A complete Odyssey in Serbian was published in 1966 by Miloš N. Đurić, and was immediately regarded as a major stylistic accomplishment. José Manuel Pabón gave a new Spanish translation in verse. Published in 1982, this translation was influenced by modernist poetry, and by Riba, in its use of “accentual hexametres”. Luo Niansheng began translating the first Chinese-language Iliad in the late 1980s, but he died before completing it; his student Wang Huansheng finished the project; Wang’s Odyssey followed in 1997. William Neill‘s translation of parts of the Odyssey into Scots language (Tales frae the Odyssey O Homer), published in 1991 by the Saltire Society, was inspired by Gavin Douglas‘ 16th-century translation. Hardwick uses Neill’s work as an example of a translation “enhancing the target language and culture”. Moshe Ha-Elion—a survivor of the death marches and Auschwitz concentration camp—translated the Odyssey into Judaeo-Spanish, a language with very few speakers. His hexameter composition was published in two parts from 2011 to 2014.

Notes and references

[edit]

- ^ Armstrong provides an example: “[…] the word κοίρανος means something like “king, ruler or leader” in a poetic context […] but these are not workaday words, despite their denotative simplicity. To translate κοίρανος simply as “king, ruler” already shaves off a level of nuance, the grandeur of an old word for – from the perspectives of both a fifth-century BCE Athenian […] – a defunct institution.”

- ^ Siobhán McElduff says their terminology for translation was very broad, and none had the modern meaning of “translate”: exprimo (squeeze out, press, translate); interpretor (explain, understand, interpret), muto (exchange, transform, translate); transfero (carry from place to place, transfer, translate; the Latin verb from which “translate” originates); and verto and its compound converto (revolve, turn, overturn, translate).”

- ^ This word has been interpreted in many ways. McElduff gives it as many-minded; Thomas E. Jenkins relates it as “of many turns”; Irene de Jong provides “with many turns of the mind”. It connotes intellectual curiosity, cunning, and being well travelled.

- ^ The only surviving line of Labeo’s Iliad is relayed by Persius’ commentary; this material was probably chosen by Persius because it was literal across multiple axes: word choice, sentence structure, and literary technique.

- ^ Petrarch wrote in a letter: “Homer is mute to me, or, rather, I am deaf to him. Still, I enjoy just looking at him and often, embracing him and sighing, I say, ‘O great man, how eagerly would

- ^ For example, Raffaello Maffeo Volaterrano’s translation in Latin prose was printed at several European cities in the late-15th and early-16th century century, including Rome, Cologne and Antwerp.

- ^ Voss produced translations of other classics, too, and eventually revised his version of Odyssey, but that received a less favourable reception.

- ^ Dacier’s Iliad was highly allegorical, and was published to positive reception; she provided historical and linguistic commentary alongside it.[63]

- Albrecht, Michael von (1997), A History of Roman Literature, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-10711-3

- Armstrong, Richard H.; Lianeri, Alexandra, eds. (2025). A Companion to the Translation of Classical Epic (1st ed.). Wiley. ISBN 9781119094265.

- Armstrong, Richard H. Introduction. In Armstrong & Lianeri (2025).

- Lianeri, Alexandra. “Introduction to Part I: Conceptual Openings In and Through Epic Translation Histories”. In Armstrong & Lianeri (2025).

- Bassnett, Susan. “Defying the Odds: How Classical Epics Continue to Survive in the Modern World”. In Armstrong & Lianeri (2025).

- Hardwick, Lorna. “Between Translation and Reception: Reading and Writing Forward and Backward in Translations of Epic”. In Armstrong & Lianeri (2025).

- Armstrong, Richard H. (2025b). “The Fighting Words Business: Thoughts on Equivalence, Localization, and Epic in English Translation”. In Armstrong & Lianeri (2025).

- McElduff, Siobhán. “What is Translation in the Ancient World?”. In Armstrong & Lianeri (2025).

- Antunes, Leonardo. “From Scheria: An Emerging Tradition of Portuegese Translations of the Odyssey”. In Armstrong & Lianeri (2025).

- Candler Hayes, Julie. “Anne Dacier’s Homer: Epic Force”. In Armstrong & Lianeri (2025).

- Baines, Paul (2000). The Complete Critical Guide to Alexander Pope. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 0-203-16993-X. OCLC 48139753.

- Barnard, John (2003). Alexander Pope: The Critical Heritage. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-19423-2.

- Blänsdorf, Jürgen; Büchner, Karl; Morel, Willy, eds. (2011). Fragmenta poetarum Latinorum epicorum et lyricorum. De Gruyter.

- Browning, Robert (1992). “The Byzantines and Homer”. In Lamberton, Robert; Keaney, John J. (eds.). Homer’s Ancient Readers: The Hermeneutics of Greek Epic’s Earliest Exegetes. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-6916-5627-4.

- Clarke, Howard W. (1981). Homer’s Readers: A Historical Introduction to the Iliad and the Odyssey. University of Delaware Press.

- Conrad, L. I. (1999). “Varietas Syriaca: Secular and Scientific Culture in the Christian Communities of Syria after the Arab Conquest”. In G. J. Reinink; Alexander Cornelis Klugkist (eds.). After Bardaisan: Studies on Continuity and Change in Syriac Christianity in Honour of Professor Han J. W. Drijvers. Peeters. pp. 85–105.

- Courtney, Edward, ed. (1993). The Fragmentary Latin Poets. Oxford University Press.

- Daiber, Hans (2017). “The Syriac Tradition in the Early Islamic Era”. In Ulrich Rudolph; Rotraud Hansberger; Peter Adamson (eds.). Philosophy in the Islamic World. Vol. 1: 8th–10th Centuries. Brill. pp. 74–94.

- Damrosch, Leopold (1987). The imaginative world of Alexander Pope. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05975-7.

- de Jong, Irene J. F. (2001). A Narratological Commentary on the Odyssey. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46478-9.

- Falcone, Maria Jennifer; Schubert, Christoph, eds. (2021). Ilias Latina: Text, Interpretation, and Reception. Brill.

- Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W.; Settis, Salvatore (2010). The Classical Tradition. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03572-0.

- Hall, Edith (2008). The Return of Ulysses: A Cultural History of Homer’s Odyssey. I. B. Tauris & Co. ISBN 978-1-84511-575-3.

The two Homeric epics formed the basis of the education of every- one in ancient Mediterranean society from at least the seventh century BCE; that curriculum was in turn adopted by Western humanists

- Hickman, Miranda B.; Kozak, Lynn, eds. (2020). The Classics in Modernist Translation. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-350-04095-3.

- Cè, Massimo. “Translating the Odyssey: Andreas Divus, Old English, and Ezra Pound’s Canto I”. In Hickman & Kozak (2020).

- Mariotti, Scaevola (1952). Livio Andronico e la traduzione artistica. Pubblicazione dell’Università di Urbino.

- McElduff, Siobhán (2013). Roman Theories of Translation: Surpassing the Source. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-81676-2.

- Pache, Corinne Ondine; Dué, Casey; Lupack, Susan; Lamberton, Robert, eds. (2020). The Cambridge Guide to Homer (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781139225649. ISBN 978-1-139-22564-9.

- Possanza, D. Mark (2004). Translating the Heavens: Aratus, Germanicus and the Poetics of Latin Translation. Peter Lang.

- Pucci, Pietro (1987). Odysseus Polytropos: Intertextual Readings in the Odyssey and the Iliad. Cornell University Press.

- Schneider, Bernd; Meckelnborg, Christina, eds. (2011). Odyssea Homeri a Francisco Griffolino Aretino in Latinum translata: Die lateinische Odyssee-Übersetzung des Francesco Griffolini. Leiden: Brill.

- Stanford, W. B. (1968). The Ulysses Theme: A Study in the Adaptability of the Traditional Hero (2nd ed.). University of Michigan Press.

- Steiner, George (1975). After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation. Oxford University Press.

Journals, news and web

[edit]

- Armstrong, Richard H. (2018). “Review of Homer: The Odyssey”. Museum Helveticum. 75 (2): 225–226. ISSN 0027-4054. JSTOR 26831950.

- Brammall, Sheldon (1 July 2018). “Review: George Chapman: Homer’s Iliad”. Translation and Literature. 27 (2). doi:10.3366/tal.2018.0339. ISSN 0968-1361. S2CID 165293864.

- Cooper, David L. (2007). “Vasilii Zhukovskii as a Translator and the Protean Russian Nation”. The Russian Review. 66 (2): 185–203. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9434.2007.00437.x. ISSN 0036-0341. JSTOR 20620532.

- Cronin, Michael (2012). “The rise of the reader and norms in twentieth-century English-language literary translation”. Studies in Translatonal Theory and Practice.

- Curran, Jane V. (1996). “Wieland’s Revival of Horace”. International Journal of the Classical Tradition. 3 (2): 171–184. doi:10.1007/BF02677914. ISSN 1073-0508. JSTOR 30222268.

- Fay, H. C. (1952). “George Chapman’s Translation of Homer’s ‘iliad’“. Greece & Rome. 21 (63): 104–111. doi:10.1017/S0017383500011578. ISSN 0017-3835. JSTOR 640882. S2CID 161366016. Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- Franco Aixelá, Javier (Autumn 2012). “La teoría os hará libres”. Vasos Comunicantes (43): 31–48.

- Gabela, Branko (6 February 1966). “Подухрат старог хеленисте: нови превод Илиаде и Одисеје“. Politika. p. 18.

- García Gual, Carlos (2015). “La primera traducción de la Odisea“. Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos (784): 128–133.

- Gray, James (1984). ““Postscript to the “Odyssey””: Pope’s Reluctant Debt to Milton”. Milton Quarterly. 18 (4): 105–116. doi:10.1111/j.1094-348X.1984.tb00295.x. ISSN 0026-4326. JSTOR 24464409.

- Horváth, István Károly (1957). “Szemle. Gondolatok az új magyar Iliászhoz“. Nagyvilág. II (1): 1424–1428.

- Muftić, Edin (2018). “Homer: An Arabic Portrait”. Pro Tempore. 13: 21–41.

- Pomian, Andrzej (1976). “Koniec Odysei (rzecz o Józefie Wittlinie)”. Orzeł Biały. XXXVI (141): 9–10.

- Rab, Zsuzsa (1972). “Grúz versek fordítása közben”. Élet és Irodalom. XVI (25): 6.

- Tanașoca, Nicolae Șerban (1973). “Cronica. În amintirea lui George Murnu, mousikòs anér“. Viața Românească. XXVI (1–2): 117–120.

- Vârgolici, Teodor (1980). “Studii. Scriitori români și epopeile clasice”. Transilvania. IX (5): 37–39.

- “The Wanderings of a Translation: From Greek to German to Russian”. Translation at Michigan. University of Michigan. 30 September 2012. Retrieved 2025-07-30.

- Zhang, Wei (2021). “Reading Homer in Contemporary China (From the 1980s Until Today)”. International Journal of the Classical Tradition. 28 (3): 353–379. doi:10.1007/s12138-020-00558-z. ISSN 1073-0508. JSTOR 48698763.