=== Massachusetts ===

=== Massachusetts ===

[[File:Migrants at dinner on the Fortitude, circa 1848.jpg|thumb|Migrant ships in the mid nineteenth century on its way to the United States]]

Unlike how the federal immigration laws regulated the movement of people from other countries, state immigration laws prior to the federal takeover limited and regulated the movement from state to state. During the mid nineteenth century, much of these state laws opposed the migration of free black slaves, Irish, and Chinese migrants movement to some states, Massachusetts being one of them. States which had access to the coast could refuse the arrival of incoming migrant ships if the state believed it would be detrimental to the local economy.

Unlike how the federal immigration laws regulated the movement of people from other countries, state immigration laws prior to the federal takeover limited and regulated the movement from state to state. During the mid nineteenth century, much of these state laws opposed the migration of free black slaves, Irish, and Chinese migrants movement to some states, Massachusetts being one of them. States which had access to the coast could refuse the arrival of incoming migrant ships if the state believed it would be detrimental to the local economy.

=== New York ===

=== New York ===

== Naturalization ==

== Naturalization ==

[[Naturalization]] has been a part of [[immigration]] for centuries. Naturalization during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century was a well used social construct that played a heavy roll in facilitating territorial expansion and [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]] integration in the United States, as well as immigration. Naturalization was a way of cementing loyalty to the United States and the pursuit of it economic and rural growth.<ref name=”:7″>{{Cite journal|title=“Allegiance and land go together”: Automatic Naturalization and the Changing Nature of Immigration in Nineteenth-Century America|url=http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14664658.2011.594649|journal=American Nineteenth Century History|date=2011-06|issn=1466-4658|pages=149–176|volume=12|issue=2|doi=10.1080/14664658.2011.594649|language=en|first=Ronald|last=Schultz}}</ref> Before the federal government took responsibility for the naturalization ceremonies that we know today, they were held by the states in court houses. in the 1780’s, the state of Philipelphia would have a court house magistrate make an migrant swear loyalty to the country, sign a paper, and with that, natralization took only minutes. That is, if the state approved the ceremony based on the immigrants economic and social performances within the state. <ref name=”:7″ />Just as it was with excluding migrants, naturalization was often reserved for those who were seen as a benefit to the overall performance of the state.<ref name=”:6″ />

== References ==

== References ==

Intro Blurb

Immigrant Nationality

[edit]

The 1845-1852 potato famine in Ireland pushed many poor Irish off the island and searching for a new place to call home. Thousands of Irish immigrated into the United States (many poor and illiterate)[1] who were looking for new opportunities. Many Irish were coming sick due to the starvation and many diseases that were occurring in Ireland which led to many needing to be hospitalized upon their arrival.[2] Because of immigrants reliance on public help, many American citizens felt like they were being taken advantage of which led to states creating immigration laws to satisfy the demands of the people. Many of the states that implemented these policies were New England states because that is where a majority of Irish immigrants were landing.

It was expensive to take care of the new immigrants because of the increased care many of them needed. Passenger brokers were supposed to pay bonds to the state in which they were docking to support their passengers. Many passenger brokers did not which increased the burden of the Irish on the American citizens who occupied cities where the Irish were landing.[2] This issue eventually led to the case Smith v. Turner in New York and Norris v. City of Boston in Massachusetts; collectively known as the passenger cases. These cases established that portions of the laws that required taxes upon each immigrant entering into those states were unconstitutional[3] and was some of the first restrictions put on states regarding immigration law.

Chinese immigrants were the target of the first federal immigration policy in the United States in 1882, but that was sparked by local and state policies trying to limit immigration and limit racial violence. Immigrants from China came to the Western United States for a chance to strike gold in California and escape rough times in China.[4] Chinese immigrants were considered unable to assimilate into American culture[5] and were subject to many acts of persecution and removal because of that prejudice.[4] The Californian government passed many laws and statutes that were later challenged by the US Supreme Court in cases like Chy Lung v. Freeman in 1875.[5] California also instituted its Anti-Coolie Act of 1862 which required Chinese immigrants to pay a tax if they were not employed or working in certain industries.[6] Legislation like this led to increased prejudice against Chinese immigrants which eventually led to federal legislation on the matter and led to many realizing that the best way to regulate immigration would be to enact it on the federal level.[5]

State Immigration Policies

[edit]

Unlike how the federal immigration laws regulated the movement of people from other countries, state immigration laws prior to the federal takeover limited and regulated the movement from state to state. During the mid nineteenth century, much of these state laws opposed the migration of free black slaves, Irish immigrants, and Chinese migrants movement to some states, Massachusetts being one of them. States which had access to the coast could refuse the arrival of incoming migrant ships if the state believed it would be detrimental to the local economy.[7]

After the commencement of the 1840’s immigration era, efforts were made through state legislature to entice European immigrants into the state of Michigan, while denying citizenship to Black men and women. This was an effort to exclude them and other undesirable migrants from the state of Michigan. due to the influx of Eastern United States migrants coming to Michigan, It was recorded in the 1900 US census that 57 percent of the states population were foreign migrants[8]. factors for this influx included the overpopulation of Europe, and the Industrialization in Germany, which killed old occupations in favor of new ones. The State of Michigan claimed to want only laborers who came at “especial invitation”, and wanted to exclude migrants such as blacks and Indians. The dual state policy which was held at the time in the 1840’s and 1850’s did well to exclude these groups from their state.

In 1835 and 1850, the state of Michigan and its presiding constitutions gave instant housing and even voting rights to white male migrants of European heritage while at the same time, denying them to freed black slaves, enticing them to exit the state and to not settle there. For example, the state of Michigan, in the 1820’s adopted a set of laws from the state of Ohio referred to as the Black Laws of 1804 and 1807. Laws like these and others made it very difficult for freed Black’s to settle in the state[8]. As a result, they were influenced to migrate out of the state to seek other means of settlement in other places.

Immigration policy in the Southern United States was mostly in place to regulate the migration of free and enslaved Black people. States like South Carolina, Georgia, and North Carolina wrote legislation in the 18th century that prohibited migration of Black people from the Caribbean because they were concerned about an uprising among enslaved individuals.[5] The Southern States eventually lobbied for federal regulation and were able to get Congress to pass laws regarding migration of Black people.

Deportation/Detention

[edit]

The Federal Government of the United States did not take full control of immigration policy until the latter half of the nineteenth century. Even today, cases such as Arizona Vs. United States are a modern representation of how states were involved in the immigration policy and deportation process back before the 1891 immigration act. On a state level, “immigration Policy”[9] decided what rights and privileges migrants had within their respective state. The majority of states shared views on migrant classes that they wanted to exclude from their states. These incuded free Black Americans, the poor, disabled bodied, and convicted migrants from Europe.[10]

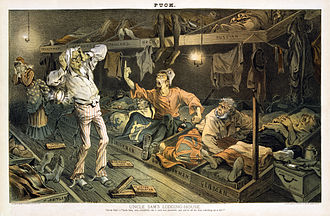

During the early 1800’s most migrants who came to the United States came to New York City; specifically to Ellis Island. Once arriving, migrants would describe the place to be “grim”[11], not like the promises that they had heard American offered. If fact, immigrants would go one to say that after each gate they passes through, they would feel “more cut off from life.”[11] Ellis Island was not just a checkpoint for migrants to get into America. It was also a prison for migrants. The Island would often be used to filter out migrants who were more or less undesirable. Due to the high anti chinese immigration, officers at Ellis Island and other local town leaders throughout the state would exclude Chinese workers.[9]

Prior to the federal takeover of immigration in the late nineteenth century, state and local leader were at the heads of many deportation and detention events. Not all deportations were done before formal hearings, as they are in formal deportations. “Self-Deportation Campaigns”[9], as well as Voluntary departure (United States) were methods of deportation and detention where the leaders of local town and state governments would use fear and other scare tactics to make life difficult for non-desirable migrants[9]. This would cause migrants to voluntarily choose to leave the state, and in some cases, leave the country. local town leaders in the west such as Charles Fayette McGlashan would be a leading figure in the Anti-Chinese sentiment and enacting these sort of state deportations and Self-deportation campaigns in the mid to late nineteenth century.[9]

Naturalization has been a part of immigration for centuries. Naturalization during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century was a well used social construct that played a heavy roll in facilitating territorial expansion and Native American integration in the United States, as well as immigration. Naturalization was a way of cementing loyalty to the United States and the pursuit of it economic and rural growth.[12] Before the federal government took responsibility for the naturalization ceremonies that we know today, they were held by the states in court houses. in the 1780’s, the state of Philipelphia would have a court house magistrate make an migrant swear loyalty to the country, sign a paper, and with that, natralization took only minutes. That is, if the state approved the ceremony based on the immigrants economic and social performances within the state. [12]Just as it was with excluding migrants, naturalization was often reserved for those who were seen as a benefit to the overall performance of the state.[7]

- ^ Connor, Dylan (2018-08-17). “The cream of the crop? Geography, networks and Irish migrant selection in the Age of Mass Migration”. UCLA International Institute.

- ^ a b Purcell, Richard J. (1948). “The New York Commissioners of Emigration and Irish Immigrants: 1847-1860”. Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review. 37 (145): 29–42. ISSN 0039-3495.

- ^ Smith George; Norris, James (December 1848). “Opinions of the Judges of the Supreme Court of the U.S. in the cases of “Smith vs. Turner,” and “Norris vs. The City of Boston.”“. heinonline.org. Retrieved 2025-11-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lew-Williams, Beth (2018). The Chinese Must Go: Violence, Exclusion, and the Making of the Alien in America (First ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674976016.

- ^ a b c d Kenny, Kevin (September 2022). “Mobility and Sovereignty: The Nineteenth-Century Origins of Immigration Restriction”. Journal of American History.

- ^ “California’s Anti-Coolie Act of 1862” (PDF). Retrieved November 29, 2025.

- ^ a b Cummings, John (1895). “Poor-Laws of Massachusetts and New York: With Appendices Containing the United States Immigration and Contract-Labor Laws”. Publications of the American Economic Association. 10 (4): 15–135. ISSN 1049-7498.

- ^ a b McAdoo, William (1983). The Settler State: Immigration Policy And The Rise Of Institutional Racism In Nineteenth Century Michigan. (volumes I And Ii) [The Settler State: Immigration Policy And The Rise Of Institutional Racism In Nineteenth Century Michigan. (volumes I And Ii)] (1st ed.). Michigan: Proquest; University of Michigan. pp. 1–600. ISBN 8324245. CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- ^ a b c d e Goodman, Adam (2021-09-14). The Deportation Machine: America’s Long History of Expelling Immigrants. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-20420-8.

- ^ Law, Anna O. (2014-10). “Lunatics, Idiots, Paupers, and Negro Seamen—Immigration Federalism and the Early American State”. Studies in American Political Development. 28 (2): 107–128. doi:10.1017/s0898588x14000042. ISSN 0898-588X.

- ^ a b Minian, Ana Raquel (2024-04-16). In the Shadow of Liberty: The Invisible History of Immigrant Detention in the United States. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-593-65425-5.

- ^ a b Schultz, Ronald (2011-06). ““Allegiance and land go together”: Automatic Naturalization and the Changing Nature of Immigration in Nineteenth-Century America”. American Nineteenth Century History. 12 (2): 149–176. doi:10.1080/14664658.2011.594649. ISSN 1466-4658.