===Solitary Creek===

===Solitary Creek===

Early in 1839 Rotton went to live at Solitary Creek (later named [[Rydal, New South Wales|Rydal]]) in the [[Central West, New South Wales|Central West]] region of [[New South Wales]], its location described as a “purling stream, in a grassy vale”.<ref name=bioBT/><ref>”New South Wales Directory, &c., of the Post Master General of the Colony, 1835”, page 188.</ref> From about February 1839 he leased the Queen Victoria Inn on the Bathurst Road near Solitary Creek, and was granted a license for the public-house. The inn provided accommodation for travellers, with four sitting rooms and five bedrooms, and included stables, paddocks and stockyards.<ref>[https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2548156 Notice], ”Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser”, 26 February 1839, page 3.</ref> The premises had been opened in July 1838 and was initially leased by Dennis Kenny, who by November 1838 had abandoned the premises with rent in arrears.<ref name=QVI>[https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/36856476 Queen Victoria Inn], ”The Australian” (Sydney), 4 May 1838, page 3.</ref>{{Ref|NoteB|[B]}}

Early in 1839 Rotton went to live at Solitary Creek (later named [[Rydal, New South Wales|Rydal]]) in the [[Central West, New South Wales|Central West]] region of [[New South Wales]], its location described as a “purling stream, in a grassy vale”.<ref name=bioBT/><ref>”New South Wales Directory, &c., of the Post Master General of the Colony, 1835”, page 188.</ref> From about February 1839 he leased the Queen Victoria Inn on the Bathurst Road near Solitary Creek, and was granted a license for the public-house. The inn provided accommodation for travellers, with four sitting rooms and five bedrooms, and included stables, paddocks and stockyards.<ref>[https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2548156 Notice], ”Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser”, 26 February 1839, page 3.</ref> The premises had been opened in July 1838 and was initially leased by Dennis Kenny, who by November 1838 had abandoned the with rent in arrears.<ref name=QVI>[https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/36856476 Queen Victoria Inn], ”The Australian” (Sydney), 4 May 1838, page 3.</ref>{{Ref|NoteB|[B]}}

Henry Rotton and Lorn Jane Macpherson were married in 1839. The couple had two children, born in 1840 and 1841. Lorn Rotton died on 11 September 1842 at Solitary Creek, aged 25.<ref name=ancestry/>

Henry Rotton and Lorn Jane Macpherson were married in 1839. The couple had two children, born in 1840 and 1841. Lorn Rotton died on 11 September 1842 at Solitary Creek, aged 25.<ref name=ancestry/>

English-born Australian politician

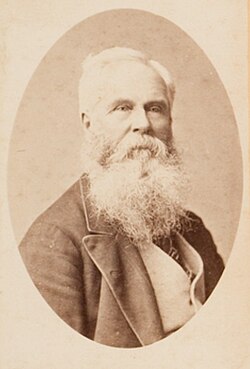

Henry Rotton (16 August 1814 – 11 October 1881) was an English-born Australian politician.

Biography

Early life

Henry Rotton was born on 16 August 1814 at Frome Selwood, county Somerset in England, the only son of Gilbert Rotton and Mary Caroline (née Humphries). His father was a solicitor.[1][2]

Young Henry received his early education at a school in Frome and afterwards at the nearby city of Wells (west of Frome).[3]

Henry Rotton developed a strong desire to enter the Royal Navy. His father consulted his nephew, naval captain Fairfax Moresby (later an admiral), in the hope of entering his son in the naval service, but he was advised it was not possible. Henry’s father then allowed his son “to take a trial trip in a merchant vessel”. However, the ship was wrecked in the West Indies. Rotton then joined a vessel bound for the African coast, but he was abandoned by the captain in the British colony of Gold Coast “without friends or resources” and suffering from yellow fever. Rotton recovered from the disease after being cared for by “some negroes” and afterwards became a guest of the Governor of Gold Coast, George Maclean.[3]

Sydney

From the Gold Coast in West Africa Rotton took a passage on a ship bound for Australia and arrived at Sydney, possibly in November 1833. He found a position as a clerk working for Mr. James, a businessman based at Parramatta, in which position he remained until early 1839.[3][4][A]

Solitary Creek

Early in 1839 Rotton went to live at Solitary Creek (later named Rydal) in the Central West region of New South Wales, its location described as a “purling stream, in a grassy vale”.[3][5] From about February 1839 he leased the Queen Victoria Inn on the Bathurst Road near Solitary Creek, and was granted a license for the public-house. The inn provided accommodation for travellers, with four sitting rooms and five bedrooms, and included stables, paddocks and stockyards.[6] The premises had been opened in July 1838 and was initially leased by Dennis Kenny, who by November 1838 had abandoned the property with rent in arrears.[7][B]

Henry Rotton and Lorn Jane Macpherson were married in 1839. The couple had two children, born in 1840 and 1841. Lorn Rotton died on 11 September 1842 at Solitary Creek, aged 25.[1]

Bathurst district

Rotton and his children moved to Bathurst in July 1843.[3] From July 1843 to 1848 Rotton held the publicans’ license of the Queen Victoria Inn on the corner of George and Piper streets in Bathurst, named after his previous public-house at Solitary Creek.[8][2]

Henry Rotton and Mary Ann Ford were married on 18 March 1844 at Kelso (across the Macquarie River from Bathurst). The couple had eleven children born from 1846 to 1871.[9][1]

In 1848 Rotton became contractor for the conveyance of post office mails. His tender for the amount of £1,200 was accepted in January 1848 for the following twelve months. The contract was for the following routes: between Penrith and Bathurst, via Hartley, “by two or more horse coaches, three times a week, performing the journey in the day”; to and from Bathurst, Molong and Wellington (once a week) and Bathurst and Carcoar (three times a week), by two horse mail cart; to and from Bathurst and O’Connell, twice a week, by one horse mail cart.[10]

By the early 1850s he was operating coaches on seven routes from Bathurst to the district townships of Orange, Wellington, Hartley, Rockley, Ophir, Sofala and Carcoar. In 1854 the Rockley, Ophir, Sofala and Carcoar routes were taken over by other contractors, but Rotton continued to operate the other coachlines until 1857.[3]

In 1853 Rotton purchased the ‘Blackdown’ pastoral property, north of Kelso, where he resided with his family. He also became part owner of several stations on the Lachlan and Macquarie rivers, including ‘Gungalman’ in the Lachlan District. Rotton was a successful breeder of horses, cattle and sheep at ‘Blackdown’, often winning prizes for his livestock at agricultural shows in the local district and in Sydney.[3][2]

Rotton was described as “a man of indomitable pluck and perseverence”.[4]

Two men who closely resembled each other had booked seats on Rotton’s coachlines. One of the men left thirty pounds in the possession of Mrs. Rotton for safe-keeping. The money was inadvertantly handed to the wrong man, who departed on the coach. Several hours later, when the real owner of the money claimed his money, Henry Rotton “went after the coach on horseback”, which he caught up with at Hartley. He found the man at dinner and forced him to give up the money and afterwards successfully prosecuted him.[4]

Rotton was a justice of the peace and sometimes acted as police magistrate for the district.[4]

Political career

At the general election held in January and February 1858 Rotton was elected to represent the electoral district of Western Boroughs in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly, an electorate that included Blayney, Carcoar and Rockley. Rotton ran against the sitting candidate, Arthur Holroyd, and was elected with a margin of six votes, polling 230 votes (or 50.7 percent) against Holroyd’s 224 votes.[11] At the declaration of the poll on 30 January Rotton declared that “he was no party man”, describing the present state of politics in the colony as “one ill defined heterogeneous mass”. He described the predominant political faction under Charles Cowper as a liberal one and he himself “would be liberal likewise, if they would consent to enact laws conferring social and religious freedom on all classes of men… such as would promote progress and rational reform, not continuing to tinker up laws which did not require it, but eradicating bad laws wherever they existed”.[12]

During his first term in parliament Rotton openly supported aspects of the liberal agenda of John Robertson and Charles Cowper, including the abolition of state aid to religion. He maintained that all the Christian denominations should be treated alike and opposed grants to the Anglican and Catholic churches.[3]

The Legislative Assembly was dissolved on 11 April 1859 and writs were issued by the Governor to proceed with an election. At the general election held in June and July 1859 Rotton decided to contest the rural electorate of Bathurst (County). Rotton and the pastoralist John Clements contested the seat, with Clements taking the conservative position of opposing the abolition of state aid to religion.[3] At the election held on 9 June 1859 Rotton was defeated, attracting only 278 votes (44.4 percent).[13] Rotton then decided to nominate for the electorate of Hartley, a district where he owned property and was known to electors. Nominations for the seat were held on 20 June 1859. The only other candidate was the solicitor John Ryan Brenan, who had previously held the rural seat of Cumberland (South Riding) on Sydney’s urban fringe. At the election held five days later Rotton was successfully elected for the seat of Hartley, receiving 281 votes (57.8 percent).[14]

At the general election held in December 1860 Rotton was one of three candidates who nominated for the Bathurst electorate (replacing the Western Boroughs electorate). The election was held on 6 December and Rotton polled second, with only 113 votes (23 percent), losing the contest against James Hart (who had previously been the member for New England).[15] Four days later Rotton nominated for the seat of Hartley, of which he was the sitting member. He was elected at the poll on 14 December against one other candidate, attracting 190 votes (54.1 percent).[16]

He opposed free selection before survey and from 1860 voted against Cowper-Robertson ministries.[2]

During this term of parliament Rotton took a conspicuous part in the railway estimates debate and was successful in his advocacy of having the allocated sum equally divided between the three main lines of the colony, rather than being weighed heavily towards extending the Southern line to Albury to connect Sydney with Melbourne.[3][17]

Bushrangers

Henry Rotton’s eldest daughter Caroline, born in December 1840 at Solitary Creek, had married Henry Keightley in December 1860 at Kelso.[18] Keightley was an assistant Gold Commissioner living at ‘Dunn’s Plains’ near Rockley, 29 miles (36 km) south of Bathurst. On the evening of Saturday, 24 October 1863, the bushrangers John Gilbert, John O’Meally, Ben Hall, John Vane and Mick Burke approached Keightley’s homestead. Keightley was about thirty yards from the house when the gang rode up and ordered him to “bail up”. Rather than obey the order Keightley ran towards the house, as the bushrangers fired at him. When he was inside the house, he and a guest, Dr. W. C. Pechey, guarded the door with a double-barrelled gun and a revolver. Keightley and Dr. Pechey continued to defend the besieged household when Keightley shot Burke in the abdomen as he tried to rush the house. The siege finally ended when Ben Hall threatened to burn the house if the defenders would not lay down their arms, giving Keightley no choice as his wife and child and two servants were sheltering in the house. After he was wounded Burke tried to shoot himself in the head with his revolver, leaving him barely alive and unconscious. With Keightley and Pechey in captivity, several of the angry bushrangers wanted to kill Keightley to avenge the shooting of Burke but eventually Hall and Gilbert decided that the Gold Commissioners life would be spared for a ransom payment of five hundred pounds (the identical amount of reward offered by the government for the apprehension of each of the bushrangers). In an attempt to treat the mortally wounded Burke, Dr. Pechey was allowed to travel to Rockley to retrieve his instruments, promising he would not raise the alarm, but the bushranger died during his absence.[19][20][21]

Caroline Keightley and Dr. Pechey then travelled to Bathurst by buggy to collect the ransom money, with the bushrangers vowing to shoot Caroline’s husband if the police were notified. Their captive was taken to a nearby hill overlooking the Bathurst road, to await their return. Pechey and Mrs. Keightley arrived at ‘Blackdown’ in the early hours of Sunday morning and roused Caroline’s father to advise him of the situation. Rotton and Dr. Pechey then rode to Bathurst and woke the manager of the Commercial Bank so they could procure the required money. The two men arrived at Keightley’s house at ‘Dunn’s Plains’ at ten o’clock in the morning. Inside the house Rotton hastily recorded the serial numbers on the notes before Dr. Pechey mounted his horse and rode to the bushrangers’ camp with the ransom money. After Keightley’s liberty was exchanged for the ransom, he and Dr. Pechey returned to the house and the bushrangers hastily left the locality. After his son-in-law had been released Rotton rode into Rockley and gave a report of the events to the police. He returned to ‘Dunn’s Plains’ and then started for Bathurst to alert the police there. However news had already reached Bathurst and near the outskirts of town he was met with a party of mounted troopers on their way to ‘Dunn’s Plains’.[19][20][21][C]

Political attempts

At the general election held from late November 1864 to early January 1865 Rotton decided to once again contest the seat of Bathurst, but was defeated by James Kemp in a two-way contest held on 21 December.[22]

Rotton was elected as a director of the Bathurst Sheep Board in 1866 and served as its chairman from 1869 until 1881. He was a member of the local public school board from 1868 and served as chairman from 1874.[23]

Rotton attempted to re-enter politics at the 1872 general election, once again nominating for the Bathurst electorate, but was defeated by Edward Combes.[24] He made another attempt in 1873, contesting the seat of East Macquarie at a by-election held on 1 December 1873, but he finished second in a field of four candidates.[25] He made one further attempt at the general election held from early December 1874 to early January 1875, contesting the seat of seat of West Macquarie against one other candidate, but polled second in the vote held on 4 January.[26]

Last years

Henry Rotton died on 11 October 1881, aged 67, at ‘Mynora’, his property near Moruya where his daughter Caroline and son-in-law, Henry Keightley, were living. At that time Keightley was the local Police Magistrate. Rotton was buried in the Baptist cemetery at Bathurst. His possessions were valued for probate at £29,000.[27][2]

Notes

- A.^ Some references state that Henry Rotton arrived in Australia in 1836, initially arriving at Kangaroo Island, South Australia, as second mate aboard the vessel Emma, after which he made his way to Sydney.[23][2] In the first report of the South Australian Company, a public corporation formed to purchase land and develop commercial and shipping operations in the new colony of South Australia, it was noted that “the brig Emma has been chartered by the month as a store ship” to supply the company’s holdings on Kangaroo Island.[28] The company’s chartered brig Emma arrived at Kingscote, Kangaroo Island, on 11 September 1836.[29]

- B.^ In May 1838 Dennis Kenny, a former sergeant of the 17th Regiment of Foot, announced that the Queen Victoria Inn at Solitary Creek, “on the new line of road from Sydney to Bathurst”, would be opened on 1 July 1838. The inn was built by Alexander Fraser of Penrith and Kenny had taken on a five-year lease for the building.[7] Kenny probably abandoned the premises with his rental payments in arrears. In November 1838 the proprietor Alexander Fraser had notices published describing Kenny as “my late tenant” and threatening to sell his household furniture by public auction unless Kenny “pays the rent due to me”.[30]

- C.^ Henry McCrummin Keightley arrived in New South Wales soon after the gold discoveries of 1851 and began working as a clerk in the General Post Office in Sydney. He was commissioned as an ensign in a volunteer regiment, the 1st Sydney Rifles, and was later promoted to lieutenant. In August 1855 Keightley was posted to Tamworth as a clerk of petty sessions, after which he was transferred as an assistant gold commissioner of the Rockley-Abercrombie goldfield, stationed at Rockley. He initially resided with a police escort at the Summer Hill copper mines seven miles south of Rockley. After his marriage to Catherine Rotton in December 1860 the government leased the ‘Dunn’s Plains’ homestead, belonging to William Bowman of Richmond, as his official residence. Keightley was promoted to police magistrate at Wellington in 1870. In 1875 he was appointed as police magistrate at Moruya and in October 1883 at Albury. Henry Keightley died in January 1887 at Sale, in the Gippsland district of Victoria. Keightley’s role in the confrontation with the bushrangers at ‘Dunn’s Plains’ in October 1863 was the inspiration for the character of ‘Mr. Knightley’ in Rolf Boldrewood‘s novel Robbery Under Arms (published in the 1880s).[21][31][32]

References

- ^ a b c Family records, Ancestry.com.

- ^ a b c d e f E. J. Lea-Scarlett (1976), Henry Rotton (1814–1881), Australian Dictionary of Biography website, National Centre of Biology, Australian National University; accessed 28 November 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Everard Digby (editor) (1889), Australian Men of Mark, Vol. I, Sydney: Charles F. Maxwell, pages 121-124; the following article has identical content: Men of the Past: Some Early Recollections: Mr. Henry Rotton, Bathurst Times, 31 January 1914, page 2.

- ^ a b c d Henry Rotton, Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 16 May 1906, page 1273.

- ^ New South Wales Directory, &c., of the Post Master General of the Colony, 1835, page 188.

- ^ Notice, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 26 February 1839, page 3.

- ^ a b Queen Victoria Inn, The Australian (Sydney), 4 May 1838, page 3.

- ^ Notice of Removal, Sydney Morning Herald, 10 July 1843, page 1.

- ^ Marriages, Sydney Morning Herald, 29 March 1844, page 3.

- ^ Conveyance of Post Office Mails, New South Wales Government Gazette (Sydney), 28 January 1848 (Issue No. 12), page 132.

- ^ Western Boroughs – 1858, ‘New South Wales Election Results 1856-2007’, Parliament of New South Wales website; accessed 28 November 2025.

- ^ Western Boroughs, Bathurst Free Press and mining Journal, 3 February 1858, page 2.

- ^ Bathurst – 1859, ‘New South Wales Election Results 1856-2007’, Parliament of New South Wales website; accessed 28 November 2025.

- ^ Hartley – 1859, ‘New South Wales Election Results 1856-2007’, Parliament of New South Wales website; accessed 28 November 2025.

- ^ Bathurst – 1860, ‘New South Wales Election Results 1856-2007’, Parliament of New South Wales website; accessed 28 November 2025.

- ^ Hartley – 1860, ‘New South Wales Election Results 1856-2007’, Parliament of New South Wales website; accessed 28 November 2025.

- ^ Progress of the Western Railway Movement, Bathurst Free Press and Mining Journal, 30 October 1861, page 2.

- ^ Married, Bathurst Free Press and Mining Journal, 26 December 1860, page 2.

- ^ a b Desperate Encounter With the Bushrangers, Sydney Morning Herald, 30 October 1863, page 5; republished from the Bathurst Times, 28 October 1863.

- ^ a b Vane & White (ed.) (1908), Chapter XXXII: ‘The Fight at Keightley’s. – Death of Mick Burke’, pages 167-179.

- ^ a b c Ransomed Gold Commissioner, Sydney Mail, 8 February 1933, page 17.

- ^ Bathurst – 1864-5, ‘New South Wales Election Results 1856-2007’, Parliament of New South Wales website; accessed 28 November 2025.

- ^ a b “Mr Henry Rotton (1814-1881)”. Former members of the Parliament of New South Wales. Retrieved 29 November 2025.; Chris N. Connolly (1983), Biographical Register of the New South Wales Parliament 1856-1901, Canberra: Australian National University Press, pages 288-289.

- ^ Bathurst – 1872, ‘New South Wales Election Results 1856-2007’, Parliament of New South Wales website; accessed 28 November 2025.

- ^ East Macquarie – By-election, ‘New South Wales Election Results 1856-2007’, Parliament of New South Wales website; accessed 28 November 2025.

- ^ West Macquarie – 1874-5, ‘New South Wales Election Results 1856-2007’, Parliament of New South Wales website; accessed 28 November 2025.

- ^ Death of Mr. Henry Rotton, Southern Argus (Goulburn), 13 October 1881, page 2.

- ^ First Report of the Directors of the South Australian Company, South Australian Gazette and Colonial Register (Adelaide), 18 June 1836, page 6.

- ^ The Courier, The Hobart Town Courier, 9 December 1836, page 2.

- ^ Sale of Household Furniture…, The Australian (Sydney), 17 November 1838, page 4.

- ^ Official Notifications, Sydney Daily Telegraph, 1 September 1883, page 3.

- ^ Deaths, Albury Banner and Wodonga Express, 14 January 1887, page 20.

- Sources