== Sources MESS ==

== Sources MESS ==

* {{Cite journal|title=Black Tradeswomen and the Making of a Taste Culture in Lower Louisiana|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/27284210|journal=Early American Studies|date=2021|issn=1543-4273|pages=735–768|volume=19|issue=4|first=Jessica|last=Blake |jstor=27284210 }}

* PHILADELPHIA-SPANISH NEW ORLEANS TRADE: 1789-1803. ARENA, CARMELO RICHARD. University of Pennsylvania ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 1959. 5904590.

* PHILADELPHIA-SPANISH NEW ORLEANS TRADE: 1789-1803. ARENA, CARMELO RICHARD. University of Pennsylvania ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 1959. 5904590.

* Mississippi’s First Federal District Court and Its Judges, 1818-1838 D Hargrove – Miss. LJ, 2014

* Mississippi’s First Federal District Court and Its Judges, 1818-1838 D Hargrove – Miss. LJ, 2014

American settler and planter (1773–1826)

Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL

|

Jengod/Benjamin Farrar |

|

|---|---|

| Born | 1773 (1773) |

| Died | 1826 (aged 52–53) |

Benjamin Farar (1773–1826), sometimes spelled Farrar, was a plantation owner in Orleans Territory and Mississippi Territory, United States. He was “one of the most prosperous planters” of the Natchez District of Mississippi[1] and also owned vast cotton plantations in Concordia Parish, Louisiana. He served as captain of militia company of mounted dragoons drawn from Adams County that were present at the transfer of New Orleans to the Americans in 1803 and were deployed for the Sabine Expedition in 18TK. His father, also Benjamin Farar, was a South Carolinian who came to the lower Mississippi River valley around the time of the American Revolutionary War and had been granted a massive tract of land near Point Coupee along False River by the Spanish government.

TERRITORIAL PAPERS VOLUME FIVE

He was known as Captain Benjamin Farar to distinguish him from his father Dr. Benjamin Farar.[2] When the first Mississippi territorial militia was organized by Governor Winthrop Sargent in 1798, Farar was named a captain of horse, along with William Moore and David Ferguson.[3] He made an oath of allegiance to the United States of America on January 1, 1799.[4] The Adams County Dragoons “continues to drill long after the war. “.

Circa 1800 he was the number-one taxpayer in the vicinity of Second Creek, followed thereafter by Anthony Hutchins and “Mrs. Surget.”[6] Amongst his taxable property was 27 slaves.[6] This was the highest number of taxable slaves held in “the richest district” of Adams County.[7] In 1803 he commanded a troop of volunteer cavalry from Mississippi that was present at the transfer of New Orleans and the Louisiana Territory from France to the United States.[8]

1803 – courthouse with Adam Tooley[9]

In 1804 the “seat of justice” for the Adams District was located near his mill, which was in turn near Second Creek.[10]

Benjamin Farar and Mary, his wife, who were settlers in the Mississippi Territory on the 27th day of Oct. 1795, claim a tract of 600 acres in Wilkinson County, on Buffalo Creek, joining lands granted to William Cocke Ellis, which land is claimed in right of the said Mary by virtue of a grant thereof by the Spanish Government to her the 16 Feb. 1789. – McBEE – 536

In November 1805 he was named a juror of the Supreme Court of Mississippi Territory at Washington.[11]

In 1806, Benjamin Farar offered a $20 reward for the capture of 26-year-old Sam, “5 feet 9 or 10 inches high, large prominent eyes, he has an impediment in his speech, is branded on the breast B. F.”[12]

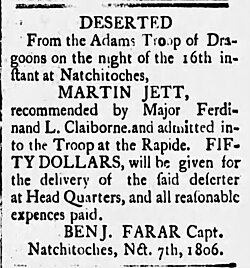

Farrar and Thomas Hinds were captains of the Mississippi dragoons during the 1806 Sabine Expedition against the Spanish.[13] He was still captain of what was called the Adams Troop of Horse.[14] His troop of horse was ordered to attend a regimental muster in September 1806.[15] In November 1806 there was finger-pointing by public letter between Farar and Ferdinand L. Claiborne about who was responsible for the conduct of a young deserter named Martin Jett.[16] Farar and Claiborne dueled at the Vidalia sandbar on November 30, 1806.[17]

1809 – horses Sabine expedition[18]

There is an 1813 lawsuit in the Louisiana Supreme Court archives between Benjamin Farar and Daniel Clark’s executors (Relf & Chew).[19]

1822 Vestryman for Trinity Episcopal Church

He owned Mississippi riverfront plantations about 20 miles below Vidalia in Concordia Parish.[21] In December 1809 his cotton crop was burned, twice, under what were considered to be suspicious circumstances.[22] The first fire took place in the dead of night: “We are informed, that a fire took place on Thurfday last, about three o’clock in the morning on a farm of Capt. BENJAMIN FARAR’S, in the parish of Concordia, Orleans Territory, by which his mill, cotton gin, and the present crop of cotton, together with a considerable portion of the last year’s crop, already baled, were entirely consumed. The ructive element was not difcovered until the heat had become so great as not to allow any person to approach within one hundred yards thereof. The damage sustained by Captain Farar in this unfortunate event, is estimated at between twenty five and thirty thousand dollars.”[23] The estimated value of the cotton was US$25,000 (equivalent to $502,606 in 2024).

“Another fire, we learn, has taken place on the plantation of Capt. Benjamin Farar, in the Parish of Concordia, Orleans Territory. The Cotton saved from the last conflagration, together with what has been picked out since, amounting in all to something less than 100,000 weight, and a temporary Cotton House, has been consumed. There can no longer exit a doubt as to the manner in which this fire has been communicated. Some unknown and malignant person is the author. Circumstances of a peculiar nature warrant us in making the assertion. It behove every good citizen to be on the watch, and endeavor to detect the infamous incendiary. A man capable of so atrocious a crime will hesitate at nothing.”[22]

A later court case record had it that “There was about 600,000 Ibs. of cotton in the seed, in the gin, when it was burned.”[24]

In 1818 two enslaved men, Greenock and Abraham, recently purchased from Robert Bell of Nashville, Tennessee, ran away from the plantation of Benjamin Farar of Second Creek.[25] In 1819 he petitioned Mississippi House of Representatives to manumit “Louisa and her daughter Betsey” as had been requested by his brother-in-law Abram Ellis in his will.[26]

He had a house in Natchez at Wall and State, facing the public square and the courthouse, said to be composed of “large and airy” rooms with a fine yard, coach house, stables, and a good kitchen.[27] After he died it became the home of Dr. William Newton Mercer, and as of 1837 it had been purchased by the owners of the adjoining Parker’s Mississippi Hotel.[27]

dunbar science[28]

- On October 14, 1794, the younger Benjamin Farar married Mary Ellis,[29] whose family had lent their name to the Ellis Cliffs along the Mississippi River. Other Ellis women married into the local Rapalje, Minor, Chotard, Gustine, and Duncan planter families, which extended the network of potential creditors upon whom he could draw. Mary Ellis Farar died October 15, 1820, in the yellow fever outbreak at Bay St. Louis that killed many members of the family.[31][32]

- Late in life, he remarried, to Jane Beverly of Virginia.[37] According to marriage registers, Benjamin Farar married Ann Tayloe Beverly in 1825 in Wilkinson County, Mississippi.[38] Beverly plantation was said to be named for this wife.[37] Ann Tayloe married second her cousin Carter Randolph in Louisiana.[39] According to one genealogy, Ann Tayloe Beverly was 15 years old at the time of the wedding.[40]

According to folklore retold by local writer Edith Wyatt Moore, “What if he did keep a sumptuous menage and dress like a London courtier, wasn’t it the custom for the gentry to keep up with London in those days? It is told that he wore gorgeous satin knee breeches with silver buckles, velvet coats in almost as many hues as Joseph’s coat and a cocked hat, powdered queue and buckled shoes to say nothing of a jeweled snuff box, lace cuffs, gold braid and silk hose. He maintained a lordly coach drawn by six matching horses and driven by a liveried coachman. There were footmen and postilian riders, also in livery.”[37]

- ^ Pinnen, Christian, “Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720–1820” (2012). Dissertations. 821. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/821

- ^ “Finding Aid for the Landry-Hume Collection MUM01796”. egrove.olemiss.edu. Retrieved 2026-02-01.

- ^ Rowland (1907), p. 240.

- ^ “490-A12-1.tif – Oaths of Allegiance to United States of America, 1798-1799”. da.mdah.ms.gov. Archived from the original on 2025-05-20. Retrieved 2026-02-01.

- ^ a b Claiborne, J. F. H. (September 3, 1879). “Letter from Hon. J. F. H. Claiborne: Seventy-Nine Years Ago”. The Clarion. p. 1. Retrieved 2025-11-24.

- ^ “Adams County Eighty Years Ago”. The Weekly Democrat. September 6, 1882. p. 1. Retrieved 2025-11-24.

- ^ “It was not until the 17th of December, 1803…” Clarion-Ledger. December 7, 1930. p. 29. Retrieved 2025-11-24.

- ^ Mississippi. (1803). Laws of the state of Mississippi.

- ^ “To the Freeholders of Adams District”. Mississippi Herald and Natchez Gazette. July 20, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved 2025-11-24.

- ^ “South Was Young: Ancient Court Records Unearthed by Mr. Seaman”. Natchez Democrat. September 19, 1909. p. 9. Retrieved 2025-11-24.

- ^ “TWENTY DOLLARS REWARD”. The Mississippi Messenger. February 3, 1806. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-09-10.

- ^ “Mississippi Engaged in Five Wars Before the Civil War”. Sun Herald. October 19, 1962. p. 4. Retrieved 2025-11-24.

- ^ “Adams Troop of Horse”. The Weekly Chronicle. January 4, 1809. p. 3. Retrieved 2025-11-24.

- ^ https://da.mdah.ms.gov/series/territorial/s488/detail/257427

- ^ “Dear Mr. Terrell”. The Mississippi Messenger. November 4, 1806. p. 3. Retrieved 2026-01-20.

- ^ Thompson, Ray M. (July 9, 1962). “Where the Gentlemen of Natchez Settled Their Differences”. The Daily Herald. Biloxi, Mississippi. p. 4. Retrieved 2025-11-24.

- ^ United States (1826). Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States being the first session of the first Congress-3rd session of the 13th Congress, March 4, 1789-Sept. 19, 1814. Washington, D.C.: Gales and Seaton.

- ^ Clark’s Executors V. Farar, Historical Archives of the Louisiana Supreme Court. University of New Orleans

- ^ “Probate Sale”. Natchez Gazette. March 10, 1821. p. 4. Retrieved 2025-11-24.

- ^ a b “Murder and Conflagration”. The Weekly Chronicle. December 23, 1809. p. 3. Retrieved 2025-11-24.

- ^ “We are informed…” The Weekly Chronicle. December 9, 1809. p. 2. Retrieved 2025-11-24.

- ^ Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Louisiana. state. 1853.

- ^ “120 Dollars Reward”. Natchez Gazette. September 9, 1818. p. 3. Retrieved 2025-11-24.

- ^ “Petition #11081902 Adams County, Mississippi, filing started January 1819 – Race and Slavery Petitions, Digital Library on American Slavery”. dlas.uncg.edu. Retrieved 2026-02-01.

- ^ a b “Sketch from a Traveler’s Notes”. The Mississippi Free Trader. March 28, 1837. p. 2. Retrieved 2025-11-24.

- ^ Cantwell, Robert (1961). Alexander Wilson: naturalist and pioneer, a biography. Internet Archive. Philadelphia, Lippincott.

- ^ “Louisiana, Marriages, 1816-1906”, , FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:V28Q-HG3), Benjamin Farrar, 1794.

- ^ a b “Obituary”. Louisiana State Gazette. October 25, 1820. p. 2. Retrieved 2026-02-01.

- ^ “The Yellow Fever”. Richmond Enquirer. November 28, 1820. p. 2. Retrieved 2026-02-01.

- ^ “Hymenal”. Mississippi Free Trader. January 11, 1820. p. 3. Retrieved 2026-02-01.

- ^ “DIED, on Saturday morning”. The Semi-Weekly Mississippi Free Trader. November 4, 1839. p. 2. Retrieved 2026-01-31.

- ^ a b Mignon, Francois (December 23, 1967). “Plantation Memo: A Woman’s Touch”. The Town Talk. p. 15. Retrieved 2026-01-31.

- ^ a b Bailey, Roy (July 1, 1962). “St. Mary’s Church Near Natchez Lies Veiled in Silence”. The Vicksburg Post (Part 1 of 2). p. 7. Retrieved 2026-01-31. & “St. Mary’s” (Part 2 of 2). p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e f “Natchez, the City Unusual: Laurel Hill by Mrs. Edith Wyatt Moore”. Tensas gazette. January 1, 1932. p. 5. Retrieved 2026-01-31.

- ^ “Mississippi, Marriages, 1800-1911”, database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:V28B-Q5R : 14 February 2020), Benjamin Farar, 1825.

- ^ “Notes and Queries”. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 37 (1): 52–79. 1929. ISSN 0042-6636.

- ^ McGill, John (1956). The Beverley family of Virginia; descendants of Major Robert Beverley, 1641-1687, and allied families. Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center. Columbia, S.C., R.L. Bryan Co., 1956. p. 586.

- ^ “Benjamin Farrar in entry for Benjamin Carter Beverly Farrar, 1826”. United States, Births and Christenings, 1867–1931. FamilySearch.

- PHILADELPHIA-SPANISH NEW ORLEANS TRADE: 1789-1803. ARENA, CARMELO RICHARD. University of Pennsylvania ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 1959. 5904590.

- Mississippi’s First Federal District Court and Its Judges, 1818-1838 D Hargrove – Miss. LJ, 2014

- The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. Texas State Historical Association. 1950.

- Valdman, Albert; Klingler, Thomas A. (1997), Valdman, Albert (ed.), “The Structure of Louisiana Creole”, French and Creole in Louisiana, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 109–144, doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-5278-6_5, ISBN 978-1-4419-3262-4, retrieved 2026-02-01

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - New Orleans and Urban Louisiana: Settlement to 1860. United States: Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 2005.

- Rowland, Dunbar, ed. (1907). “Territorial Militia”. Mississippi; comprising sketches of counties, towns, events, institutions, and persons, arranged in cyclopedic form. Vol. II. Atlanta: Southern Historical Association Publishing. pp. 240–243.

- Thrasher, Albert (1996). “On to New Orleans”: Louisiana’s heroic 1811 slave revolt (Second ed.). New Orleans, LA: A. Thrasher. ISBN 978-0-9644595-0-2.

A

- Rogers, George C. (1970). The history of Georgetown County, South Carolina (1st ed.). Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-87249-143-4.

- BRAWLING AND DUELING ON THE NORTH LOUISIANA FRONTIER, 1803-1861: A SKETCH. Academic Journal North Louisiana Historical Association Journal. Fall1990, Vol. 21 Issue 4, p99-108. 10p. Historical Period: 1803 to 1861

SOURCES CLEAN & used

[edit]

- Burnett, Edmund Cody (1910). Papers relating to Bourbon County, Georgia, 1785–1786. New York: MacMillan Company. OCLC 49477860 – via HathiTrust.

- Din, Gilbert (1981). “War Clouds on the Mississippi: Spain’s 1785 Crisis in West Florida”. Florida Historical Quarterly. 60 (1) 6 – via library.ucf.edu.

- Fabel, Robin F. A. (1988). The Economy of British West Florida, 1763–1783. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0312-9. LCCN 86004328. OCLC 13332013.

- Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo (2005). Slavery and African Ethnicities in the Americas. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. doi:10.5149/9780807876862_hall. ISBN 978-0-8078-2973-8. JSTOR 10.5149/9780807876862_hall. LCCN 2005005917. OCLC 816498633. OL 2983392W.

- James, D. Clayton (1993) [1968]. Antebellum Natchez. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-1860-3. LCCN 68028496. OCLC 28281641.

- Lester, Dick M. (1993). “John Dick of New Orleans”. Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 34 (3): 357–365. ISSN 0024-6816. JSTOR 4233042.

- McBee, May Wilson (1953). The Natchez Court Records, 1767–1805: Abstracts of Early Records. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Edwards Brothers, Inc. – via Internet Archive, digitized from a copy held at the Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

- Rothstein, Morton (1979). “The Changing Social Networks and Investment Behavior of a Slaveholding Elite in the Ante Bellum South: Some Natchez Nabobs, 1800–1860”. In Greenfield, Sidney M.; Strickon, Arnold; Aubey, Robert T. (eds.). Entrepreneurs in Cultural Context. School of American Research, Advanced Seminar Series. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 65–88. ISBN 978-0-8263-0504-6. LCCN 78021433. OCLC 4859059.

Manuscript collections

[edit]

- Brown, Laura Clark, ed. (2009). “BUTLER (RICHARD) PAPERS (Mss. 1000, 1069) Inventory by Laura Clark Brown Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Baton Rouge, Louisiana” (PDF).

- Buchanan, Douglas; Michaelis, Kathryn, eds. (July 2013) [1997]. “Landry-Hume Collection (MUM01796), Archives and Special Collections”. Oxford, Mississippi: J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi.

- Cowan, Barry, ed. (2025) [2003]. “ELLIS-FARAR PAPERS Mss. 1000 Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collection Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library” (PDF). Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Libraries.