|}

|}

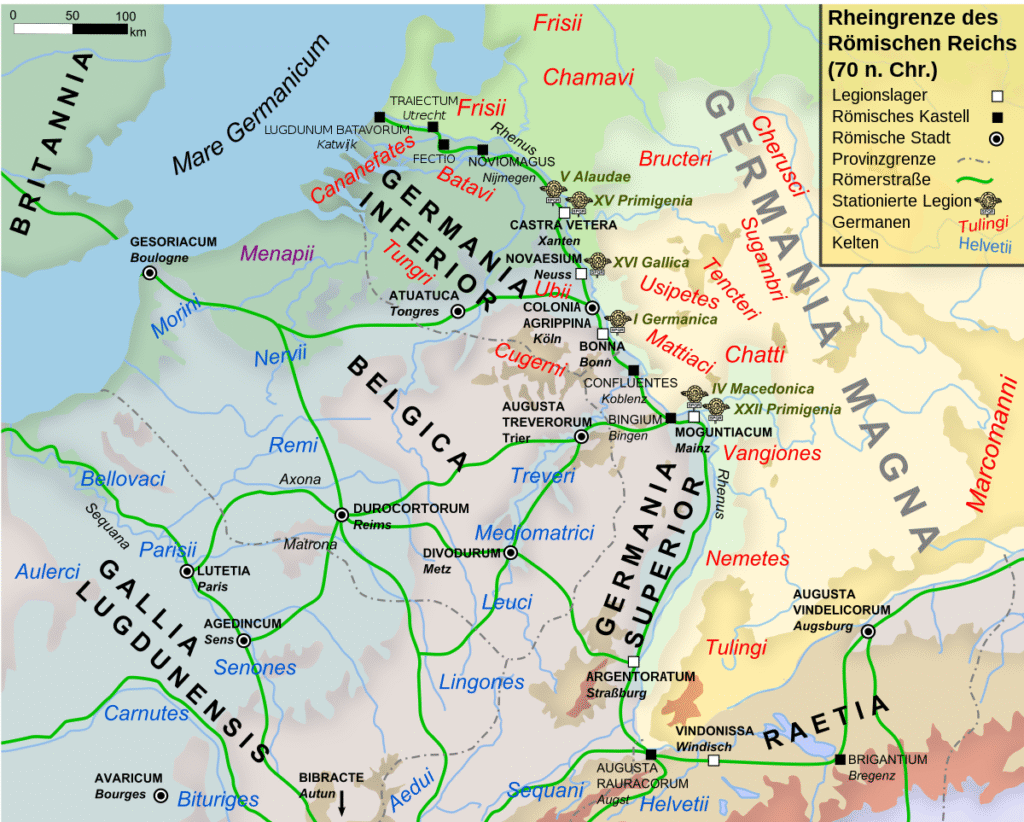

The region of Batavia, was described by Roman authors as the largest island in the delta, stretching from the sea to its easternmost point at the first major split in the Rhine. The Waal formed the southern boundary, while the northern boundary, which became the northern frontier of the Roman empire, ran roughly along the course of the modern [[Oude Rijn (Gelderland)|Old Rhine in Gelderland]] and [[Oude Rijn (Utrecht and South Holland)|Old Rhine in South Holland]]. Sharing the island with the Batavi were the [[Canninefates]].<ref>Pliny, ”Natural History”, [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D4%3Achapter%3D29 4.29(15)]</ref> Tacitus described them as being the same as the Batavi in origin, language, and valour, though inferior in numbers.<ref>Tacitus, ”History”, [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Tac.%20Hist.%204.15 4.15]</ref>

The region of Batavia, was described by Roman authors as the largest island in the delta, stretching from the sea to its easternmost point at the first major split in the Rhine. The Waal formed the southern boundary, while the northern boundary, which became the northern frontier of the Roman empire, ran roughly along the course of the modern [[Oude Rijn (Gelderland)|Old Rhine in Gelderland]] and [[Oude Rijn (Utrecht and South Holland)|Old Rhine in South Holland]]. Sharing the island with the Batavi were the [[Canninefates]].<ref>Pliny, ”Natural History”, [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D4%3Achapter%3D29 4.29(15)] and Tacitus, ”History”, [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Tac.%20Hist.%204.15 4.15]</ref>

It is not clear exactly when the Romans and Batavi first came into contact.{{sfn|Callies|1975}} It may have been Caesar himself who settled the Batavi in the delta.{{sfn|Roymans|2004|p=251}} In any case, they probably settled in the Rhine delta some time between 55 BC and 15 BC, when the Romans had already become dominant in the area, although it has also been argued that it could have even happened before Caesar’s arrival in the region.<ref>{{harvnb|Callies|1975}}. {{harvnb|Roymans|2004|p=26}} says 50 BC-15 BC or 50 BC-12 BC ({{harvnb|Roymans|2004|p=55}}) </ref> [[Tacitus]], writing about 100 AD, reported that the Batavi, who he described as the most valorous of all the peoples {{lang|la|gentes}} on the Rhine, had originally been a part of the [[Chatti]], a tribe living by his time near the [[Main river]]. Like the Batavi however, they were not mentioned by Caesar. According to Tacitus, domestic strife ({{lang|la|seditione domestica}}) forced them to move away from the other Chatti.<ref name=tacgerm>Cornelius Tacitus, ”Germany and its Tribes” [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0083%3Achapter%3D29 1.29]</ref><ref name=tacthist>Tacitus, ”History” [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0080%3Abook%3D4%3Achapter%3D12 4.12]</ref> He described this as a place “where they would become part of the Roman Empire” {{lang|la|in quibus pars Romani imperii fierent}}.<ref name=tacgerm/>

It is not clear exactly when the Romans and Batavi first came into contact.{{sfn|Callies|1975}} It may have been Caesar himself who settled the Batavi in the delta.{{sfn|Roymans|2004|p=251}} In any case, they probably settled in the Rhine delta some time between 55 BC and 15 BC, when the Romans had already become dominant in the area, although it has also been argued that it could have even happened before Caesar’s arrival in the region.<ref>{{harvnb|Callies|1975}}. {{harvnb|Roymans|2004|p=26}} says 50 BC-15 BC or 50 BC-12 BC (p55)</ref> [[Tacitus]], writing about 100 AD, reported that the Batavi, who he described as the most valorous of all the peoples {{lang|la|gentes}} on the Rhine, had originally been a part of the [[Chatti]], a tribe living by his time near the [[Main river]] the Batavi were not mentioned by Caesar. According to Tacitus, domestic strife ({{lang|la|seditione domestica}}) forced to move away from the other Chatti.<ref name=tacgerm>Cornelius Tacitus, ”Germany and its Tribes” [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0083%3Achapter%3D29 1.29]</ref><ref name=tacthist>Tacitus, ”History” [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0080%3Abook%3D4%3Achapter%3D12 4.12]</ref>

Tacitus described them seizing “the furthest corner of the Gallic coast, empty of inhabitants”.<ref name=tacthist/> However, the idea that the delta had previously been uninhabited is contradicted by archaeological evidence, which shows continuous habitation from at least the third century BC onward.{{sfn|Roymans|2004|p=27}} It is however possible that an elite group of such “Chatto-Batavi” moved to the delta, and brought traditions with them.{{sfn|Roymans|2004|pp=27,55,61}}

Tacitus described “the furthest corner of the Gallic coast, empty of inhabitants”.<ref name=tacthist/> However, the idea that the delta had previously been uninhabited is contradicted by archaeological evidence, which shows continuous habitation from at least the third century BC onward.{{sfn|Roymans|2004|p=27}} It is that an elite group of such “Chatto-Batavi” moved to the delta and traditions with them.{{sfn|Roymans|2004|pp=27,55,61}}

Tacitus also emphasized the unusual nature of their agreements with Rome. “Their honour still remains, and the mark of their ancient alliance: they are neither burdened with tribute, nor worn down by tax-collectors. Exempt from imposts and contributions, and set apart only for the purposes of war, they are, as it were, weapons and armour, reserved for battle.”<ref name=tacgerm/> And in another work: “Nor were they worn down by obligations (a rare thing in alliance with stronger powers): they supplied only men and arms for the empire, long trained in German wars, and afterwards increased in renown by service in Britain, when cohorts were sent over there, which, by ancient custom, were commanded by the noblest of their countrymen. At home, too, there was a levy of cavalry, with a special skill in swimming: keeping hold of their arms and horses, they charged across the Rhine in unbroken squadrons.”<ref name=tacthist/>

Tacitus also emphasized the unusual nature of their agreements with Rome. “Their honour still remains, and the mark of their ancient alliance: they are neither burdened with tribute, nor worn down by tax-collectors. Exempt from imposts and contributions, and set apart only for the purposes of war, they are, as it were, weapons and armour, reserved for battle.”<ref name=tacgerm/> And in another work: “Nor were they worn down by obligations (a rare thing in alliance with stronger powers): they supplied only men and arms for the empire, long trained in German wars, and afterwards increased in renown by service in Britain, when cohorts were sent over there, which, by ancient custom, were commanded by the noblest of their countrymen. At home, too, there was a levy of cavalry, with a special skill in swimming: keeping hold of their arms and horses, they charged across the Rhine in unbroken squadrons.”<ref name=tacthist/>

Germanic tribe

The Batavi or Batavians were a Roman era Germanic people that lived on the island of Batavia in the Rhine delta, in what is now the Netherlands. This place was already referred to by Julius Caesar as the “island of the Batavi” in his account of his campaigns in Gaul in 58-52 BC – although he did not explain who the Batavi were. As a result of his campaigns; the Romans subsequently took control of all of Gaul including Batavia.

The later Roman author Tacitus reported the Batavi had once been a part of the Chatti, but they moved after an internal conflict. He also reported that they had a special old alliance with Rome, as major contributors to the Roman military who did not pay any other form of tribute or tax. Some modern scholars such as Nico Roymans have suggested that this agreement may have gone back to Caesar himself, and reflected their contributions to his personal bodyguard, which fought for him in his Roman civil war and evolved into the bodyguard of his successors in the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

The name was applied to several military units employed by the Romans that were originally raised among the Batavi.

In the third century AD Rome lost control of Batavia to tribes including the Chamavi, collectively described by near contemporaries as Franks, Frisii or (according to one 4th century source) Saxons. When they were able to enter it again the Romans moved large parts of the native population to other parts of the empire. By 358 AD the region was being governed with Roman agreement by a Frankish people from north of the Rhine called the Salians, who still pressure from the Chamavi.

The Batavi themselves are not mentioned directly by Julius Caesar in his commentary on his Gallic wars, which lasted from 58 to 52 BC. However, he described the Insula Batavorum, “Island of the Batavi”:[2]

-

-

The Meuse (Latin: Mosa) rises from mount Vosges, which is in the territories of the Lingones; and, having received a branch of the Rhine, which is called the Waal (Vacalus), forms the island of the Batavi, and not more than eighty miles from it it falls into the ocean. But the Rhine takes its source among the Lepontii, who inhabit the Alps , and is carried with a rapid current for a long distance […] where it has approached the Ocean, it splits into several branches, creating many vast islands, a great part of which are inhabited by savage barbarian nations. Of these some are thought to live on fish and the eggs of birds. With many mouths, the river flows into the Ocean.

-

The region of Batavia, was described by Roman authors as the largest island in the delta, stretching from the sea to its easternmost point at the first major split in the Rhine. The Waal and Meuse formed the southern boundary, while the northern boundary, which became the northern frontier of the Roman empire, ran roughly along the course of the modern Old Rhine in Gelderland and Old Rhine in South Holland. Sharing the island with the Batavi were the Canninefates who Tacitus described as being the same as the Batavi in origin, language, and valour, though inferior in numbers.[3]

It is not clear exactly when the Romans and Batavi first came into contact. It may have been Caesar himself who settled the Batavi in the delta. In any case, they probably settled in the Rhine delta some time between 55 BC and 15 BC, when the Romans had already become dominant in the area, although it has also been argued that it could have even happened before Caesar’s arrival in the region.[6] Tacitus, writing about 100 AD, reported that the Batavi, who he described as the most valorous of all the peoples gentes on the Rhine, had originally been a part of the Chatti, a tribe living by his time near the Main river, who like the Batavi were not mentioned by Caesar. According to Tacitus, domestic strife (seditione domestica) forced the Batavi to move away from the other Chatti.[7][8]

Tacitus described this as a place where the Batavi “would become part of the Roman Empire” (in quibus pars Romani imperii fierent),[7] and said they seized “the furthest corner of the Gallic coast, empty of inhabitants”.[8] However, the idea that the delta had previously been uninhabited is contradicted by archaeological evidence, which shows continuous habitation from at least the third century BC onward. It is more likely that an elite group of such “Chatto-Batavi” moved to the delta and integrated themselves into the pre-existing culture, bringing new traditions with them.

Tacitus also emphasized the unusual nature of their agreements with Rome. “Their honour still remains, and the mark of their ancient alliance: they are neither burdened with tribute, nor worn down by tax-collectors. Exempt from imposts and contributions, and set apart only for the purposes of war, they are, as it were, weapons and armour, reserved for battle.”[7] And in another work: “Nor were they worn down by obligations (a rare thing in alliance with stronger powers): they supplied only men and arms for the empire, long trained in German wars, and afterwards increased in renown by service in Britain, when cohorts were sent over there, which, by ancient custom, were commanded by the noblest of their countrymen. At home, too, there was a levy of cavalry, with a special skill in swimming: keeping hold of their arms and horses, they charged across the Rhine in unbroken squadrons.”[8]

Caesar himself already had a unit of about 400 Germani horsemen, who he decided from the beginning to keep with him on his Gallic campaign.[11] These Germanic troops are also mentioned in his accounts of the subsequent civil wars, being used by him against Pompey’s Roman forces in Spain and Alexandria, and on at least one occasion they were used to attack across a river. The poet Lucan explicitly says that Caesar had Batavi with him during the civil war, and this is probably correct. This Germanic force is believed to have developed into the Julio-Claudian dynasty‘s personal Germanic bodyguard, sometimes called the Numerus Batavorum, which was in later generations dominated by Batavi and Ubii.

Archaeological evidence

[edit]

Archeological evidence suggests they lived in small villages, composed of six to 12 houses in the very fertile lands between the rivers, and lived by agriculture and cattle-raising. Finds of horse skeletons in graves suggest a strong equestrian preoccupation.[citation needed]

The strategic position, to wit the high bank of the Waal offering an unimpeded view far into Germania Transrhenana (Germania Beyond the Rhine), was recognized first by Drusus, who built a massive fortress (castra) and a headquarters (praetorium) in imperial style.[citation needed] The latter was in use until the Batavian revolt. On the south bank of the Waal (in what is now Nijmegen) a Roman administrative center was built, called Oppidum Batavorum. This centre was razed during the Batavian Revolt. The Smetius Collection was instrumental in settling the debate about the exact location of the Batavians.

Dio Cassius describes a surprise tactic employed by Aulus Plautius against the “barbarians”—the British Celts— at the battle of the River Medway, 43:

The barbarians thought that Romans would not be able to cross it without a bridge, and consequently bivouacked in rather careless fashion on the opposite bank; but he sent across a detachment of Germanic tribesmen, who were accustomed to swim easily in full armour across the most turbulent streams. […] Thence the Britons retired to the river Thames at a point near where it empties into the ocean and at flood-tide forms a lake. This they easily crossed because they knew where the firm ground and the easy passages in this region were to be found; but the Romans in attempting to follow them were not so successful. However, the Germans swam across again and some others got over by a bridge a little way up-stream, after which they assailed the barbarians from several sides at once and cut down many of them. (Cassius Dio, Roman History, Book 60:20)

It is uncertain how they were able to accomplish this feat. The late fourth century writer on Roman military affairs Vegetius mentions soldiers using reed rafts, drawn by leather leads, to transport equipment across rivers.[13] But the sources suggest the Batavi were able to swim across rivers actually wearing full armour and weapons. This would only have been possible by the use of some kind of buoyancy device: Ammianus Marcellinus mentions that the Cornuti regiment swam across a river floating on their shields “as on a canoe” (357).[14] Since the shields were wooden, they may have provided sufficient buoyancy[citation needed]

The Batavi were used to form the bulk of the Emperor’s personal Germanic bodyguard from Augustus to Galba. They also provided a contingent for their indirect successors, the Emperor’s horse guards, the Equites singulares Augusti.

A Batavian contingent was used in an amphibious assault on Ynys Mon (Anglesey), taking the assembled Druids by surprise, as they were only expecting Roman ships.[15]

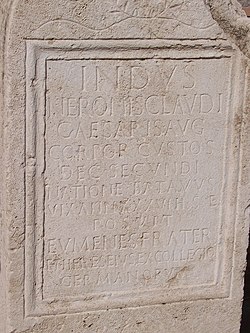

Numerous altars and tombstones of the cohorts of Batavi, dating to the second century and third century, have been found along Hadrian’s Wall, notably at Castlecary and Carrawburgh. As well as in Germany, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Romania and Austria.

Revolt of the Batavi

[edit]

Despite the alliance, one of the high-ranking Batavi, Julius Paullus, to give him his Roman name, was executed by Fonteius Capito on a false charge of rebellion. His kinsman Gaius Julius Civilis was paraded in chains in Rome before Nero; though he was acquitted by Galba, he was retained at Rome, and when he returned to his kin in the year of upheaval in the Roman Empire, 69, he headed a Batavian rebellion. He managed to capture Castra Vetera, the Romans’ lost two legions, while two others (I Germanica and XVI Gallica) were controlled by the rebels. The rebellion became a real threat to the Empire when the conflict escalated to northern Gaul and Germania. The Roman army retaliated and invaded the insula Batavorum. A bridge was built over the river Nabalia, where the warring parties approached each other on both sides to negotiate peace. The narrative was told in great detail in Tacitus’ History, book iv, although, unfortunately, the narrative breaks off abruptly at the climax. Following the uprising, Legio X Gemina was housed in a stone castra to keep an eye on the Batavians.

After the defeat of the revolt, the Batavi royal clan lost some of its authority and by about 100 AD, the Batavi state or civitas Batavorum was given municipium status within the Roman administrative system.

Although inscriptional evidence shows that many residents still identified primarily as Batavi, during the 2nd and early third centuries there is also a new tendency of residents who referred to themselves as people of the civitas capital at Noviomagus, or Ulpia Noviomagus, (modern Nijmegen). This may have been influenced not only by the decreased importance of the old royal family, but also by the increasing proportion of people there who now had Roman citizenship, or who descended from new settlers from other parts of the empire, such as veterans and traders.

During the crisis of the third century and particularly the revolt of Carausius, the Romans lost control of the Rhine delta. The Panegyrici Latini report that the area was taken over by Franks and Frisians, including the Chamavi. When the Roman military reasserted itself under the new tetrarchy, it moved large numbers of people to other regions. The population and agricultural activity decreased dramatically, and the Romans had given it up as an area for normal taxation and governance.

Some Frankish dediticii were allowed to remain in Batavia around 293-294 AD. Franks who were also later allowed to settle in Texandria by emperor Constans in 342 AD, after fighting there in 341 AD. Julian the apostate also associated the usurper Magnentius, who had killed Constans and ruled the region in 350-353 AD, with the Franks and Saxons of this region. By 358 the Salians were accepted by the Romans as the local rulers of Batavia.[18]

Julian created new military units named after the Salians, Chamavii and other inhabitants of the delta.[19]

In the Late Roman army there was still a unit called Batavi. The name of the Bavarian town of Passau descends from the Roman Batavis, which was named after the Batavi. The town’s name is old as it shows the typical effects of the High German consonant shift (b > p, t > ss).

The Batavian revival

[edit]

In the 16th-century emergence of a popular foundation story and origin myth for the Dutch people, the Batavians came to be regarded as their ancestors during their national struggle for independence during the Eighty Years’ War.[20][21] The mix of fancy and fact in the Cronyke van Hollandt, Zeelandt ende Vriesland (called the Divisiekroniek) by the Augustinian friar and humanist Cornelius Gerardi Aurelius, first published in 1517, brought the spare remarks in Tacitus’ newly rediscovered Germania to a popular public; it was being reprinted as late as 1802.[22] Contemporary Dutch virtues of independence, fortitude and industry were fully recognizable among the Batavians in more scholarly history represented in Hugo Grotius‘ Liber de Antiquitate Republicae Batavicorum (1610). The origin was perpetuated by Romeyn de Hooghe’s Spiegel van Staat der Vereenigden Nederlanden (“Mirror of the State of the United Netherlands,” 1706), which also ran to many editions, and it was revived in the atmosphere of Romantic nationalism in the late eighteenth-century reforms that saw a short-lived Batavian Republic and, in the colony of the Dutch East Indies, a capital that was named Batavia. Though since Indonesian independence the city is called Jakarta, its inhabitants up to the present still call themselves Betawi or Orang Betawi, i.e. “People of Batavia” – a name ultimately derived from the ancient Batavians.[23]

The success of this tale of origins was mostly due to resemblance in anthropology, which was based on tribal knowledge. Being politically and geographically inclusive, this historical vision filled the needs of Dutch nation-building and integration in the 1890–1914 era.

However, a disadvantage of this historical nationalism soon became apparent. It suggested there were no strong external borders, while allowing for the fairly clear-cut internal borders that were emerging as the society polarized into three parts. After 1945, the tribal knowledge lost its grip on anthropology and mostly vanished.[24] Modern variants of the Batavian founding myth are made more accurate by pointing out that the Batavians were one part of the ancestry of the Dutch people – together with the Frisians, Franks and Saxons – by tracing patterns of DNA. Echoes of this cultural continuity can still be found among various areas of Dutch modern culture, such as the very popular replica of the ship Batavia that can today be found in Lelystad.

- ^ “C. Julius Caesar, Gallic War, Book 4, chapter 10″.

- ^ Pliny, Natural History, 4.29(15) and Tacitus, History, 4.15

- ^ Callies 1975. Roymans 2004, p. 26 says 50 BC-15 BC or 50 BC-12 BC (p.55)

- ^ a b c Cornelius Tacitus, Germany and its Tribes 1.29

- ^ a b c Tacitus, History 4.12

- ^ Roymans 2004, p. 20 citing “C. Julius Caesar, Gallic War, Book 7, chapter 13″.

- ^ Vegetius De re militari III.7

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus XVI.11

- ^ Tacitus Agricola 18.3–5

- ^ Dierkens & Périn 2003 p.168 citing Eumenius, Panegyric VIII(5) written about 298 AD.

- ^ “Zosimus, New History. London: Green and Chaplin (1814). Book 3”. tertullian.org.

- ^ This section follows Simon Schama, The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age, (New York) 1987, ch. II “Patriotic Scripture”, especially pp. 72 ff.

- ^ The Batavian Myth: A Study Pack from the Department of Dutch, University College London

- ^ I. Schöffer, “The Batavian myth during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,” in P. A. M. Geurts and A. E. M. Janssen, Geschiedschrijving in Nederland (‘Gravenhage) 1981:84–109, noted by Schama 1987.

- ^ Knorr, Jacqueline (2014). Creole Identity in Postcolonial Indonesia. Volume 9 of Integration and Conflict Studies. Berghahn Books. p. 91. ISBN 9781782382690.

- ^ Beyen, Marnix (2000). “A Tribal Trinity: the Rise and Fall of the Franks, the Frisians and the Saxons in the Historical Consciousness of the Netherlands since 1850”. European History Quarterly. 30 (4): 493–532. doi:10.1177/026569140003000402. ISSN 0265-6914. S2CID 145656182. Fulltext: EBSCO

- Callies, Horst (1975), “Bataver § 1. Historisches”, in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 2 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, pp. 90–91, ISBN 978-3-11-006740-8

- Derks, Tom (2009). “Ethnic identity in the Roman frontier. The epigraphy of Batavi and other Lower Rhine tribes”. In Derks, Ton; Roymans, Nico (eds.). Ethnic Constructs in Antiquity: The Role of Power and Tradition. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-8964-078-9.

- Dierkens, Alain; Périn, Patrick (2003), “The 5th-century advance of the Franks in Belgica II: history and archaeology”, Essays on the Early Franks, Barkhuis, pp. 165–193

- Roymans, Nico (2004). Ethnic Identity and Imperial Power: The Batavians in the Early Roman Empire. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-5356-705-0.

- Roymans, Nico (2009). “Hercules and the construction of a Batavian identity in the context of the Roman empire”. In Derks, Tom; Roymans, Nico (eds.). Ethnic Constructs in Antiquity: The Role of Power and Tradition. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-8964-078-9.

- Roymans, Nico; Heeren, Stijn (2021), “Romano-Frankish interaction in the Lower Rhine frontier zone from the late 3rd to the 5th century – Some key archaeological trends explored”, Germania, 99: 133–156, doi:10.11588/ger.2021.92212

- van Rossum, J.A. (2004), “The end of the Batavian auxiliaries as ‘national’ units”, in de Ligt, Luuk; Hemelrijk, Emily; Singor, H.W. (eds.), In Roman Rule and Civic Life: Local and Regional Perspectives. Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire, Impact of Empire, vol. 4, Brill, doi:10.1163/9789004401655_008, ISBN 9789004401655

- Brunt, P. A. (1960). “Tacitus on the Batavian revolt”. Latomus. 19 (3): 494–517. ISSN 0023-8856. JSTOR 41523591.

- Hassall, M. W. C. (1970). “Batavians and the Roman Conquest of Britain”. Britannia. 1: 131–136. doi:10.2307/525836. JSTOR 525836. S2CID 163783165.

- Martin, Stéphane (2019), “The Batavian Countryside: Storage in a Non-Villa Landscape”, Rural Granaries in Northern Gaul (Sixth Century BCE – Fourth Century CE), From Archaeology to Economic History, vol. 8, Brill, pp. 106–127, ISBN 978-90-04-38903-8, JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctvrxk32d.11

- Speidel, Michael P. (1994). Riding for Caesar: The Roman Emperor’s Horseguard. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-78255-9.

- van Groesen, Michiel. “The Batavian Myth”. University College London. A Study Pack from the Department of Dutch. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- Van Enckevort, Harry; Heirbaut, Elly N. A. (2015). “Nijmegen, from Oppidum Batavorum to Vlpia Noviomagus, civitas of the Batavi: Two successive civitas-capitals”. Gallia. 72 (1): 285–298. doi:10.4000/gallia.1577. ISSN 0016-4119. JSTOR 44744321.

- Weeda, Leendert; van der Poel, Marc (2014). “Vergil and the Batavians (“Aeneid” 8.727)”. Mnemosyne. 67 (4): 588–612. doi:10.1163/1568525X-12341310. ISSN 0026-7074. JSTOR 24521754.

- Woodside, M. St. A. (1937). “The Role of Eight Batavian Cohorts in the Events of 68-69 A.D.”. Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 68: 277–283. doi:10.2307/283269. JSTOR 283269.