=== Late stage: Heart morphogenesis ===

=== Late stage: Heart morphogenesis ===

”Pitx2” activates or represses multiple downstream genes and transcription factors in precursor cells of the left heart field, affecting heart development<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Campione |first=M. |last2=Ros |first2=M. A. |last3=Icardo |first3=J. M. |last4=Piedra |first4=E. |last5=Christoffels |first5=V. M. |last6=Schweickert |first6=A. |last7=Blum |first7=M. |last8=Franco |first8=D. |last9=Moorman |first9=A. F. |date=2001-03-01 |title=Pitx2 expression defines a left cardiac lineage of cells: evidence for atrial and ventricular molecular isomerism in the iv/iv mice |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11180966 |journal=Developmental Biology |volume=231 |issue=1 |pages=252–264 |doi=10.1006/dbio.2000.0133 |issn=0012-1606 |pmid=11180966}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Logan |first=M. |last2=Pagán-Westphal |first2=S. M. |last3=Smith |first3=D. M. |last4=Paganessi |first4=L. |last5=Tabin |first5=C. J. |date=1998-08-07 |title=The transcription factor Pitx2 mediates situs-specific morphogenesis in response to left-right asymmetric signals |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9708733 |journal=Cell |volume=94 |issue=3 |pages=307–317 |doi=10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81474-9 |issn=0092-8674 |pmid=9708733}}</ref>. One example includes the transcription factor [[Homeobox protein Nkx-2.5|Nkx2-5,]] which Pitx2 regulates through methods such as chromatin remodelling or through intermediate transcription factors. Nkx2-5 contributes to proper curvature and positioning of atria and ventricles, as well as regulating genes involved in [[atrioventricular node]] and bundle formation<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Lyons |first=I. |last2=Parsons |first2=L. M. |last3=Hartley |first3=L. |last4=Li |first4=R. |last5=Andrews |first5=J. E. |last6=Robb |first6=L. |last7=Harvey |first7=R. P. |date=1995-07-01 |title=Myogenic and morphogenetic defects in the heart tubes of murine embryos lacking the homeo box gene Nkx2-5 |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7628699 |journal=Genes & Development |volume=9 |issue=13 |pages=1654–1666 |doi=10.1101/gad.9.13.1654 |issn=0890-9369 |pmid=7628699}}</ref>. Nkx2-5 is one of the key transcription factors necessary in heart development, and is most commonly found to be mutated in patients with congenital heart disorders<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Schott |first=J. J. |last2=Benson |first2=D. W. |last3=Basson |first3=C. T. |last4=Pease |first4=W. |last5=Silberbach |first5=G. M. |last6=Moak |first6=J. P. |last7=Maron |first7=B. J. |last8=Seidman |first8=C. E. |last9=Seidman |first9=J. G. |date=1998-07-03 |title=Congenital heart disease caused by mutations in the transcription factor NKX2-5 |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9651244 |journal=Science (New York, N.Y.) |volume=281 |issue=5373 |pages=108–111 |doi=10.1126/science.281.5373.108 |issn=0036-8075 |pmid=9651244}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Costa |first=Mauro W. |last2=Guo |first2=Guanglan |last3=Wolstein |first3=Orit |last4=Vale |first4=Molly |last5=Castro |first5=Maria L. |last6=Wang |first6=Libin |last7=Otway |first7=Robyn |last8=Riek |first8=Peter |last9=Cochrane |first9=Natalie |last10=Furtado |first10=Milena |last11=Semsarian |first11=Christopher |last12=Weintraub |first12=Robert G. |last13=Yeoh |first13=Thomas |last14=Hayward |first14=Christopher |last15=Keogh |first15=Anne |date=2013-06 |title=Functional characterization of a novel mutation in NKX2-5 associated with congenital heart disease and adult-onset cardiomyopathy |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23661673 |journal=Circulation. Cardiovascular Genetics |volume=6 |issue=3 |pages=238–247 |doi=10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000057 |issn=1942-3268 |pmc=3816146 |pmid=23661673}}</ref>.

”Pitx2” activates or represses multiple downstream genes and transcription factors in precursor cells of the left heart field, affecting heart development<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Campione |first=M. |last2=Ros |first2=M. A. |last3=Icardo |first3=J. M. |last4=Piedra |first4=E. |last5=Christoffels |first5=V. M. |last6=Schweickert |first6=A. |last7=Blum |first7=M. |last8=Franco |first8=D. |last9=Moorman |first9=A. F. |date=2001-03-01 |title=Pitx2 expression defines a left cardiac lineage of cells: evidence for atrial and ventricular molecular isomerism in the iv/iv mice |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11180966 |journal=Developmental Biology |volume=231 |issue=1 |pages=252–264 |doi=10.1006/dbio.2000.0133 |issn=0012-1606 |pmid=11180966}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Logan |first=M. |last2=Pagán-Westphal |first2=S. M. |last3=Smith |first3=D. M. |last4=Paganessi |first4=L. |last5=Tabin |first5=C. J. |date=1998-08-07 |title=The transcription factor Pitx2 mediates situs-specific morphogenesis in response to left-right asymmetric signals |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9708733 |journal=Cell |volume=94 |issue=3 |pages=307–317 |doi=10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81474-9 |issn=0092-8674 |pmid=9708733}}</ref>. One example includes the transcription factor [[Homeobox protein Nkx-2.5|Nkx2-5,]] which Pitx2 regulates through methods such as chromatin remodelling or through intermediate transcription factors. Nkx2-5 contributes to proper curvature and positioning of atria and ventricles, as well as regulating genes involved in [[atrioventricular node]] and bundle formation<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Lyons |first=I. |last2=Parsons |first2=L. M. |last3=Hartley |first3=L. |last4=Li |first4=R. |last5=Andrews |first5=J. E. |last6=Robb |first6=L. |last7=Harvey |first7=R. P. |date=1995-07-01 |title=Myogenic and morphogenetic defects in the heart tubes of murine embryos lacking the homeo box gene Nkx2-5 |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7628699 |journal=Genes & Development |volume=9 |issue=13 |pages=1654–1666 |doi=10.1101/gad.9.13.1654 |issn=0890-9369 |pmid=7628699}}</ref>. Nkx2-5 is one of the key transcription factors necessary in heart development, and is most commonly found to be mutated in patients with congenital heart disorders<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Schott |first=J. J. |last2=Benson |first2=D. W. |last3=Basson |first3=C. T. |last4=Pease |first4=W. |last5=Silberbach |first5=G. M. |last6=Moak |first6=J. P. |last7=Maron |first7=B. J. |last8=Seidman |first8=C. E. |last9=Seidman |first9=J. G. |date=1998-07-03 |title=Congenital heart disease caused by mutations in the transcription factor NKX2-5 |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9651244 |journal=Science (New York, N.Y.) |volume=281 |issue=5373 |pages=108–111 |doi=10.1126/science.281.5373.108 |issn=0036-8075 |pmid=9651244}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Costa |first=Mauro W. |last2=Guo |first2=Guanglan |last3=Wolstein |first3=Orit |last4=Vale |first4=Molly |last5=Castro |first5=Maria L. |last6=Wang |first6=Libin |last7=Otway |first7=Robyn |last8=Riek |first8=Peter |last9=Cochrane |first9=Natalie |last10=Furtado |first10=Milena |last11=Semsarian |first11=Christopher |last12=Weintraub |first12=Robert G. |last13=Yeoh |first13=Thomas |last14=Hayward |first14=Christopher |last15=Keogh |first15=Anne |date=2013-06 |title=Functional characterization of a novel mutation in NKX2-5 associated with congenital heart disease and adult-onset cardiomyopathy |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23661673 |journal=Circulation. Cardiovascular Genetics |volume=6 |issue=3 |pages=238–247 |doi=10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000057 |issn=1942-3268 |pmc=3816146 |pmid=23661673}}</ref>.

Other downstream effectors of ”pitx2” are involved in cytoskeletal organization, cell polarity and extracellular matrix remodeling, and various signalling pathways such as [[Wnt signaling pathway|Wnt]]<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Ai |first=Di |last2=Liu |first2=Wei |last3=Ma |first3=Lijiang |last4=Dong |first4=Feiyan |last5=Lu |first5=Mei-Fang |last6=Wang |first6=Degang |last7=Verzi |first7=Michael P. |last8=Cai |first8=Chenleng |last9=Gage |first9=Philip J. |last10=Evans |first10=Sylvia |last11=Black |first11=Brian L. |last12=Brown |first12=Nigel A. |last13=Martin |first13=James F. |date=2006-08-15 |title=Pitx2 regulates cardiac left-right asymmetry by patterning second cardiac lineage-derived myocardium |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16836994 |journal=Developmental Biology |volume=296 |issue=2 |pages=437–449 |doi=10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.009 |issn=0012-1606 |pmc=5851592 |pmid=16836994}}</ref>. Because these specific genes are only activated on the left side of the embryo, cells on the left side of the heart proliferate, elongate, and curve differently in comparison to cells on the right side<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Campione |first=Marina |last2=Franco |first2=Diego |date=2016-12-09 |title=Current Perspectives in Cardiac Laterality |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29367577 |journal=Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease |volume=3 |issue=4 |pages=34 |doi=10.3390/jcdd3040034 |issn=2308-3425 |pmc=5715725 |pmid=29367577}}</ref>. ”Pitx2” not only activates left-specific genes, but suppresses signalling pathways that are dominant on the right side of the embryo, such as [[Bone morphogenetic protein|BMP]] and [[Fibroblast growth factor 8|FGF8]]<ref>{{Citation |last=Yu |first=Xueyan |title=Expression and Function of Pitx2 in Chick Heart Looping |date=2013 |work=Madame Curie Bioscience Database [Internet] |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK6521/ |access-date=2025-12-03 |publisher=Landes Bioscience |language=en |last2=Wang |first2=Shusheng |last3=Chen |first3=YiPing}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Fischer |first=Anja |last2=Viebahn |first2=Christoph |last3=Blum |first3=Martin |date=2002-10-29 |title=FGF8 Acts as a Right Determinant during Establishment of the Left-Right Axis in the Rabbit |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982202012228 |journal=Current Biology |volume=12 |issue=21 |pages=1807–1816 |doi=10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01222-8 |issn=0960-9822}}</ref>. Overall, the differential gene expression patterns across the left-right axis caused by ”pitx2” affects cardiac looping, signalling the tubular heart to twist rightward (D-looping)<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Ramsdell |first=Ann F. |date=2005-12-01 |title=Left-right asymmetry and congenital cardiac defects: getting to the heart of the matter in vertebrate left-right axis determination |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16289136 |journal=Developmental Biology |volume=288 |issue=1 |pages=1–20 |doi=10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.038 |issn=0012-1606 |pmid=16289136}}</ref>.

== Developmental defects during tubular heart stage ==

== Developmental defects during tubular heart stage ==

The term tubular heart has two definitions, one for developmental biology, and one for evolutionary biology. In evolutionary biology, the term refers to a peristaltic heart tube that evolved in early Bilateria, which consists of a single layer of contracting mesoderm but lacks chambers, valves, and blood vessels.[1]

In developmental biology, the tubular heart or primitive heart tube is the earliest stage of heart development in vertebrates.[2] The heart is the first functional organ to form during human embryogenesis, beginning in the third week.[3][4] In the cardiogenic region of the embryo, paired endocardial tubes fuse to form a single linear structure known as the tubular heart.[5][6] This tube later undergoes looping and separation to form the multi-chambered heart.

Embryonic origin

After gastrulation, human embryos consist of three germ layers, ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. The tubular heart forms primarily from splanchnic mesoderm of the lateral plate mesoderm around day 18 of development.[7] Signals from the adjacent endoderm induce mesodermal cells, known as blood islands, to differentiate into angioblasts.[8] Through vasculogenesis at day 20, angioblasts organize into an endothelial lining that form the paired endocardial tubes.[9][10] These tubes form on either side of the embryo’s midline within the cardiogenic region. Behind them, two coelomic spaces appear within the lateral plate mesoderm.

Folding

The tubular heart develops through folding in two directions. By day 21-22, lateral folding brings the paired endocardial tubes together, fusing them into a single primitive heart tube. The coelomic spaces merge to form a single horseshoe-shaped intraembryonic coelom, which later becomes the pericardial cavity.[11] The heart tube is suspended within the cavity by the dorsal mesocardium, which is a temporary layer of tissue that connects to the developing heart tube, and later degenerates to allow further growth.[12] Cephalocaudal folding bends the embryo’s head and tail, moving the developing heart tube from the head region into the pericardial cavity.[2][13]

Layers

The tubular heart consists of three layers essential for proper heart function, corresponding to those in the adult human heart: endocardium, myocardium, and epicardium, from inside to outside.[10][12] The endocardium is derived from the endothelial lining and acts as a barrier between blood and surrounding tissues. The myocardium is composed of cardiac myoblasts. It constitutes the muscular bulk of the heart and generates the cardiac jelly, a matrix layer that separates it from the endocardium.[14] This layer is responsible for the contractile function of the heart. The epicardium (visceral serous layer of pericardium) forms later from mesothelial cells of the proepicardium, providing a protective covering for the heart.[12][15]

Structures

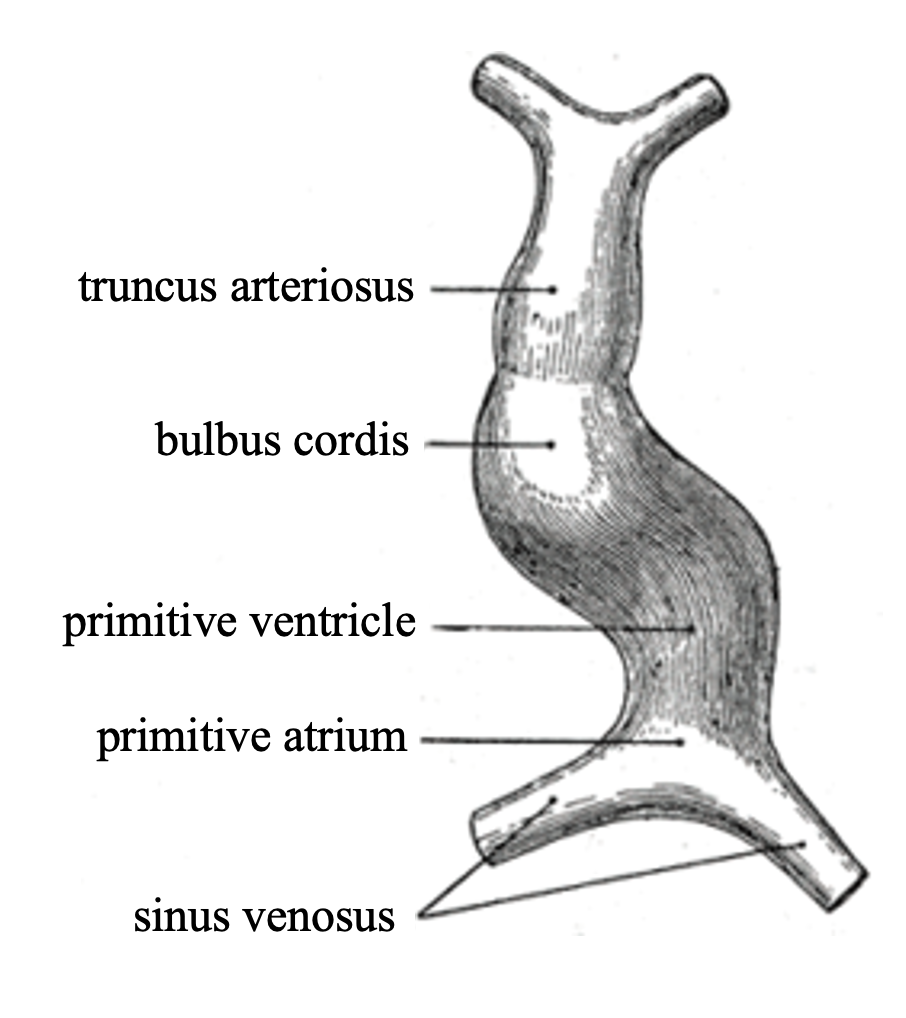

By day 22, the tubular heart divides into five regions, arranged from inflow to outflow: sinus venosus, primitive atrium, primitive ventricle, bulbus cordis, and truncus arteriosus.[16]

Fate mapping

The five regions later give rise to chambers and great vessels of the mature heart. The sinus venosus will become posterior part of the right atrium with the primary cardiac pacemaker sinoatrial node from its right horn, and the coronary sinus from the left horn.[17] The primitive atrium will develop into the rough anterior walls of both right and left atria. The primitive ventricle will develop into the trabeculated part of the left ventricle.[16][18] The bulbus cordis will elongate and form the trabeculated part of the right ventricle and the smooth outflow tracts of both ventricles. The truncus arteriosus will form the pulmonary trunk and ascending aorta that carry blood away from the heart.[19][20] Blood flow is driven by rhythmic myocardial contractions that propel blood from sinus venosus to truncus arteriosus. This unidirectional flow in the valveless heart is different from the coordinated chamber contractions of the adult heart.[3][10]

Cardiac looping

Around day 23, the heart tube begins to elongate and bend, initiating the process of cardiac looping.[6][21][22] This process rearranges the regions of the primitive heart tube so that all regions are in the correct positions for features of the mature heart to develop. It occurs in three main phases: the C-shaped, S-shaped and advanced looping stages.[23][24]

During the C-shaped phase, the initially straight heart tube bends towards the right, forming a loop that marks the beginning of cardiac asymmetry. The middle part becomes the ventricular region, while the arterial end remains relatively straight.[23][25] Meanwhile, new myocardial cells are added at both ends, causing the tube to elongate and the loop to deepen.

In the subsequent S-shaped phase, the dorsal mesocardium begins to break down, allowing the heart to move freely within the pericardial cavity. This allows for the atrium and inflow tracts to bend dorsally and upwards, while the ventricles and outflow tracts bend ventrally and downwards, producing an S-shaped configuration.[23]

At the advanced looping stage, the primitive atrium moves closer to the head with respect to the primitive ventricle, and the sinus venosus becomes located dorsally to the atria.[21] By the end of looping, all primitive segments of the heart tube are rearranged into the correct positions they will occupy in the mature heart’s structure. These segments then continue to remodel, including chamber formation and septation, to produce the fully functional adult heart.[25][26]

Gene regulation

Early stage: left-right patterning

Heart development is largely affected by left-right patterning genes in early embryogenesis[27]. Around gastrulation (14-16 days after fertilization), the node, a major signalling center, is formed along the midline of the embryo[28]. Once the node is formed, motile cilia begin to rotate clockwise, generating a leftward flow of extracellular fluid[29][30]. This directional flow moves morphogens and signalling factors towards the left side of the embryo, activating the Nodal signalling pathway[31].

Nodal activates transcription factors Smad 2 and Smad 3, which then activates the gene Lefty[32]. Lefty is a feedback inhibitor of Nodal signalling, as it inhibits Nodal once transcribed. Nodal is a self-enhancing signalling molecule, meaning its transcription binds to its own receptors to create a positive feedback loop[33]. Lefty prevents Nodal signalling from spreading beyond the midline by diffusing faster than Nodal and inhibiting its transcription[34].

Another mechanism to ensure Nodal signalling remains localized to the left side of the embryo is ZIC3, a transcription factor present at the midline of the embryo, acting as a midline barrier by activating genes such as Lefty1 that suppress Nodal signalling[35][36]. Together, Lefty and ZIC3 ensure localization of nodal signalling. By day 19 of development, Nodal activates pitx2 on the left side of the embryo[37].

Late stage: Heart morphogenesis

Pitx2 activates or represses multiple downstream genes and transcription factors in precursor cells of the left heart field, affecting heart development[38][39]. One example includes the transcription factor Nkx2-5, which Pitx2 regulates through methods such as chromatin remodelling or through intermediate transcription factors. Nkx2-5 contributes to proper curvature and positioning of atria and ventricles, as well as regulating genes involved in atrioventricular node and bundle formation[40]. Nkx2-5 is one of the key transcription factors necessary in heart development, and is most commonly found to be mutated in patients with congenital heart disorders[41][42].

Other downstream effectors of pitx2 are involved in cytoskeletal organization, cell polarity and extracellular matrix remodeling, and various signalling pathways such as Wnt[43]. Because these specific genes are only activated on the left side of the embryo, cells on the left side of the heart proliferate, elongate, and curve differently in comparison to cells on the right side[44]. Pitx2 not only activates left-specific genes, but suppresses signalling pathways that are dominant on the right side of the embryo, such as BMP and FGF8[45][46]. Overall, the differential gene expression patterns across the left-right axis caused by pitx2 affects cardiac looping, signalling the tubular heart to twist rightward (D-looping)[47].

Developmental defects during tubular heart stage

Dysregulations during the tubular heart stage can lead to various congenital heart defects (CHDs).

References

- ^ Bishopric, Nanette H. (2005). “Evolution of the Heart from Bacteria to Man”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1047 (1): 13–29. Bibcode:2005NYASA1047…13B. doi:10.1196/annals.1341.002. ISSN 1749-6632. PMID 16093481.

- ^ a b Rocha, Layla Ianca Queiroz; Oliveira, Maria Fabiele da Silva; Dias, Lucas Castanhola; Franco de Oliveira, Moacir; de Moura, Carlos Eduardo Bezerra; Magalhães, Marcela dos Santos (January 2023). “Heart morphology during the embryonic development of Podocnemis unifilis Trosquel 1948 (Testudines: Podocnemididae)”. The Anatomical Record. 306 (1): 193–212. doi:10.1002/ar.25041. ISSN 1932-8486. PMID 35808951.

- ^ a b Männer, Jörg; Wessel, Armin; Yelbuz, T. Mesud (April 2010). “How does the tubular embryonic heart work? Looking for the physical mechanism generating unidirectional blood flow in the valveless embryonic heart tube”. Developmental Dynamics. 239 (4): 1035–1046. doi:10.1002/dvdy.22265. ISSN 1058-8388. PMID 20235196.

- ^ Schleich, J-Marc (May 2002). “Development of the human heart: days 15–21”. Heart. 87 (5): 487. doi:10.1136/heart.87.5.487. ISSN 1355-6037. PMC 1767109. PMID 11997429.

- ^ Kidokoro, Hinako; Yonei-Tamura, Sayuri; Tamura, Koji; Schoenwolf, Gary C.; Saijoh, Yukio (2018-04-01). “The heart tube forms and elongates through dynamic cell rearrangement coordinated with foregut extension”. Development. 145 (7) dev152488. doi:10.1242/dev.152488. ISSN 1477-9129. PMC 5963862. PMID 29490984.

- ^ a b Farraj, Kristen L.; Zeltser, Roman (2025), “Embryology, Heart Tube”, StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29763109, retrieved 2025-10-31

- ^ Yonei-Tamura, Sayuri; Ide, Hiroyuki; Tamura, Koji (June 2005). “Splanchnic (visceral) mesoderm has limb-forming ability according to the position along the rostrocaudal axis in chick embryos”. Developmental Dynamics. 233 (2): 256–265. doi:10.1002/dvdy.20391. ISSN 1058-8388.

- ^ Ferkowicz, Michael J.; Yoder, Mervin C. (September 2005). “Blood island formation: longstanding observations and modern interpretations”. Experimental Hematology. 33 (9): 1041–1047. doi:10.1016/j.exphem.2005.06.006. PMID 16140152.

- ^ Yoder, Mervin C. (June 2010). “Is Endothelium the Origin of Endothelial Progenitor Cells?”. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 30 (6): 1094–1103. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.191635. ISSN 1079-5642. PMID 20453169.

- ^ a b c Betts, J. Gordon; Young, Kelly A.; Wise, James A.; Johnson, Eddie; Poe, Brandon; Kruse, Dean H.; Korol, Oksana; Johnson, Jody E.; Womble, Mark (2022-04-20). “19.5 Development of the Heart – Anatomy and Physiology 2e | OpenStax”. openstax.org. Retrieved 2025-10-31.

- ^ DeRuiter, M. C.; Poelmann, R. E.; VanderPlas-de Vries, I.; Mentink, M. M. T.; Gittenberger-de Groot, A. C. (1992-04-01). “The development of the myocardium and endocardium in mouse embryos”. Anatomy and Embryology. 185 (5): 461–473. doi:10.1007/BF00174084. ISSN 1432-0568. PMID 1567022.

- ^ a b c Snarr, Brian S.; Kern, Christine B.; Wessels, Andy (October 2008). “Origin and fate of cardiac mesenchyme”. Developmental Dynamics. 237 (10): 2804–2819. doi:10.1002/dvdy.21725. ISSN 1058-8388. PMID 18816864.

- ^ “Cardiovascular development and malformation”. Taylor & Francis: 239–264. 2016-04-19. doi:10.3109/9781420073447-16. ISBN 978-0-429-14676-3. Archived from the original on 2025-05-07.

- ^ Männer, Jörg; Yelbuz, Talat Mesud (2019-02-27). “Functional Morphology of the Cardiac Jelly in the Tubular Heart of Vertebrate Embryos”. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 6 (1): 12. doi:10.3390/jcdd6010012. ISSN 2308-3425. PMC 6463132. PMID 30818886.

- ^ Félétou, Michel (2011), “Multiple Functions of the Endothelial Cells”, The Endothelium: Part 1: Multiple Functions of the Endothelial Cells—Focus on Endothelium-Derived Vasoactive Mediators, Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences, retrieved 2025-10-31

- ^ a b Taber, Larry A.; Perucchio, Renato (2000-07-01). “Modeling Heart Development”. Journal of Elasticity and the Physical Science of Solids. 61 (1): 165–197. doi:10.1023/A:1011082712497. ISSN 1573-2681.

- ^ Faber, Jaeike W.; Boukens, Bastiaan J.; Oostra, Roelof-Jan; Moorman, Antoon F. M.; Christoffels, Vincent M.; Jensen, Bjarke (May 2019). “Sinus venosus incorporation: contentious issues and operational criteria for developmental and evolutionary studies”. Journal of Anatomy. 234 (5): 583–591. doi:10.1111/joa.12962. ISSN 1469-7580. PMC 6481585. PMID 30861129.

- ^ “Development of the Heart | Anatomy and Physiology II”. courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2025-10-31.

- ^ Orts-Llorca, F.; Puerta Fonolla, J.; Sobrado, J. (January 1982). “The formation, septation and fate of the truncus arteriosus in man”. Journal of Anatomy. 134 (Pt 1): 41–56. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 1167935. PMID 7076544.

- ^ “Embryology”. www.utmb.edu. Retrieved 2025-10-31.

- ^ a b Romero Flores, Brenda G.; Villavicencio Guzmán, Laura; Salazar García, Marcela; Lazzarini, Roberto (2023-06-23). “Normal development of the heart: a review of new findings”. Boletín Médico del Hospital Infantil de México (in Spanish). 80 (2). doi:10.24875/BMHIM.22000138. ISSN 0539-6115.

- ^ Mathew, Philip; Bordoni, Bruno (2025), “Embryology, Heart”, StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30725998, retrieved 2025-10-31

- ^ a b c Männer, Jörg (2000). “Cardiac looping in the chick embryo: A morphological review with special reference to terminological and biomechanical aspects of the looping process”. The Anatomical Record. 259 (3): 248–262. doi:10.1002/1097-0185(20000701)259:3<248::AID-AR30>3.0.CO;2-K. ISSN 1097-0185. PMID 10861359.

- ^ McQueen, Charlene A. (2010). Comprehensive toxicology (2nd ed.). Oxford: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-046884-6.

- ^ a b Linask, Kersti K.; Lash, James W. (1998), de la Cruz, María Victoria; Markwald, Roger R. (eds.), “Morphoregulatory Mechanisms Underlying Early Heart Development: Precardiac Stages to the Looping, Tubular Heart”, Living Morphogenesis of the Heart, Boston, MA: Birkhäuser Boston, pp. 1–41, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-1788-6_1, ISBN 978-1-4612-7283-0, retrieved 2025-10-31

- ^ Mjaatvedt, Corey H.; Yamamura, Hideshi; Wessels, Andy; Ramsdell, Anne; Turner, Debi; Markwald, Roger R. (1999), “Mechanisms of Segmentation, Septation, and Remodeling of the Tubular Heart”, Heart Development, Elsevier, pp. 159–177, doi:10.1016/b978-012329860-7/50012-x, ISBN 978-0-12-329860-7, retrieved 2025-10-31

- ^ Hamada, Hiroshi; Tam, Patrick P. L. (2014). “Mechanisms of left-right asymmetry and patterning: driver, mediator and responder”. F1000prime Reports. 6: 110. doi:10.12703/P6-110. ISSN 2051-7599. PMC 4275019. PMID 25580264.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Gilbert, S. F.; Barresi, M. J. F. (2017). “Developmental Biology, 11th Edition 2016”. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 173 (5): 1430–1430. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.38166. ISSN 1552-4833.

- ^ Nonaka, Shigenori; Yoshiba, Satoko; Watanabe, Daisuke; Ikeuchi, Shingo; Goto, Tomonobu; Marshall, Wallace F.; Hamada, Hiroshi (2005-07-26). “De Novo Formation of Left–Right Asymmetry by Posterior Tilt of Nodal Cilia”. PLOS Biology. 3 (8): e268. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030268. ISSN 1545-7885.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Dykes, Iain M. (2014-04-08). “Left Right Patterning, Evolution and Cardiac Development”. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 1 (1): 52–72. doi:10.3390/jcdd1010052. ISSN 2308-3425. PMC 5947769. PMID 29755990.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Hirokawa, Nobutaka; Tanaka, Yosuke; Okada, Yasushi; Takeda, Sen (2006-04-07). “Nodal flow and the generation of left-right asymmetry”. Cell. 125 (1): 33–45. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.002. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 16615888.

- ^ Dykes, Iain M. (2014-04-08). “Left Right Patterning, Evolution and Cardiac Development”. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 1 (1): 52–72. doi:10.3390/jcdd1010052. ISSN 2308-3425. PMC 5947769. PMID 29755990.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Schier, Alexander F. (2009-11). “Nodal morphogens”. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 1 (5): a003459. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a003459. ISSN 1943-0264. PMC 2773646. PMID 20066122. CS1 maint: article number as page number (link)

- ^ Müller, Patrick; Rogers, Katherine W.; Jordan, Ben M.; Lee, Joon S.; Robson, Drew; Ramanathan, Sharad; Schier, Alexander F. (2012-05-11). “Differential Diffusivity of Nodal and Lefty Underlies a Reaction-Diffusion Patterning System”. Science. 336 (6082): 721–724. doi:10.1126/science.1221920. PMC 3525670. PMID 22499809.

- ^ Ramsdell, Ann F. (2005-12-01). “Left-right asymmetry and congenital cardiac defects: getting to the heart of the matter in vertebrate left-right axis determination”. Developmental Biology. 288 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.038. ISSN 0012-1606. PMID 16289136.

- ^ Herman, G. E.; El-Hodiri, H. M. (2002). “The role of ZIC3 in vertebrate development”. Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 99 (1–4): 229–235. doi:10.1159/000071598. ISSN 1424-859X. PMID 12900569.

- ^ Branford, W. W.; Essner, J. J.; Yost, H. J. (2000-07-15). “Regulation of gut and heart left-right asymmetry by context-dependent interactions between xenopus lefty and BMP4 signaling”. Developmental Biology. 223 (2): 291–306. doi:10.1006/dbio.2000.9739. ISSN 0012-1606. PMID 10882517.

- ^ Campione, M.; Ros, M. A.; Icardo, J. M.; Piedra, E.; Christoffels, V. M.; Schweickert, A.; Blum, M.; Franco, D.; Moorman, A. F. (2001-03-01). “Pitx2 expression defines a left cardiac lineage of cells: evidence for atrial and ventricular molecular isomerism in the iv/iv mice”. Developmental Biology. 231 (1): 252–264. doi:10.1006/dbio.2000.0133. ISSN 0012-1606. PMID 11180966.

- ^ Logan, M.; Pagán-Westphal, S. M.; Smith, D. M.; Paganessi, L.; Tabin, C. J. (1998-08-07). “The transcription factor Pitx2 mediates situs-specific morphogenesis in response to left-right asymmetric signals”. Cell. 94 (3): 307–317. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81474-9. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 9708733.

- ^ Lyons, I.; Parsons, L. M.; Hartley, L.; Li, R.; Andrews, J. E.; Robb, L.; Harvey, R. P. (1995-07-01). “Myogenic and morphogenetic defects in the heart tubes of murine embryos lacking the homeo box gene Nkx2-5”. Genes & Development. 9 (13): 1654–1666. doi:10.1101/gad.9.13.1654. ISSN 0890-9369. PMID 7628699.

- ^ Schott, J. J.; Benson, D. W.; Basson, C. T.; Pease, W.; Silberbach, G. M.; Moak, J. P.; Maron, B. J.; Seidman, C. E.; Seidman, J. G. (1998-07-03). “Congenital heart disease caused by mutations in the transcription factor NKX2-5”. Science (New York, N.Y.). 281 (5373): 108–111. doi:10.1126/science.281.5373.108. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 9651244.

- ^ Costa, Mauro W.; Guo, Guanglan; Wolstein, Orit; Vale, Molly; Castro, Maria L.; Wang, Libin; Otway, Robyn; Riek, Peter; Cochrane, Natalie; Furtado, Milena; Semsarian, Christopher; Weintraub, Robert G.; Yeoh, Thomas; Hayward, Christopher; Keogh, Anne (2013-06). “Functional characterization of a novel mutation in NKX2-5 associated with congenital heart disease and adult-onset cardiomyopathy”. Circulation. Cardiovascular Genetics. 6 (3): 238–247. doi:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000057. ISSN 1942-3268. PMC 3816146. PMID 23661673.

- ^ Ai, Di; Liu, Wei; Ma, Lijiang; Dong, Feiyan; Lu, Mei-Fang; Wang, Degang; Verzi, Michael P.; Cai, Chenleng; Gage, Philip J.; Evans, Sylvia; Black, Brian L.; Brown, Nigel A.; Martin, James F. (2006-08-15). “Pitx2 regulates cardiac left-right asymmetry by patterning second cardiac lineage-derived myocardium”. Developmental Biology. 296 (2): 437–449. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.009. ISSN 0012-1606. PMC 5851592. PMID 16836994.

- ^ Campione, Marina; Franco, Diego (2016-12-09). “Current Perspectives in Cardiac Laterality”. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 3 (4): 34. doi:10.3390/jcdd3040034. ISSN 2308-3425. PMC 5715725. PMID 29367577.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Yu, Xueyan; Wang, Shusheng; Chen, YiPing (2013), “Expression and Function of Pitx2 in Chick Heart Looping”, Madame Curie Bioscience Database [Internet], Landes Bioscience, retrieved 2025-12-03

- ^ Fischer, Anja; Viebahn, Christoph; Blum, Martin (2002-10-29). “FGF8 Acts as a Right Determinant during Establishment of the Left-Right Axis in the Rabbit”. Current Biology. 12 (21): 1807–1816. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01222-8. ISSN 0960-9822.

- ^ Ramsdell, Ann F. (2005-12-01). “Left-right asymmetry and congenital cardiac defects: getting to the heart of the matter in vertebrate left-right axis determination”. Developmental Biology. 288 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.038. ISSN 0012-1606. PMID 16289136.